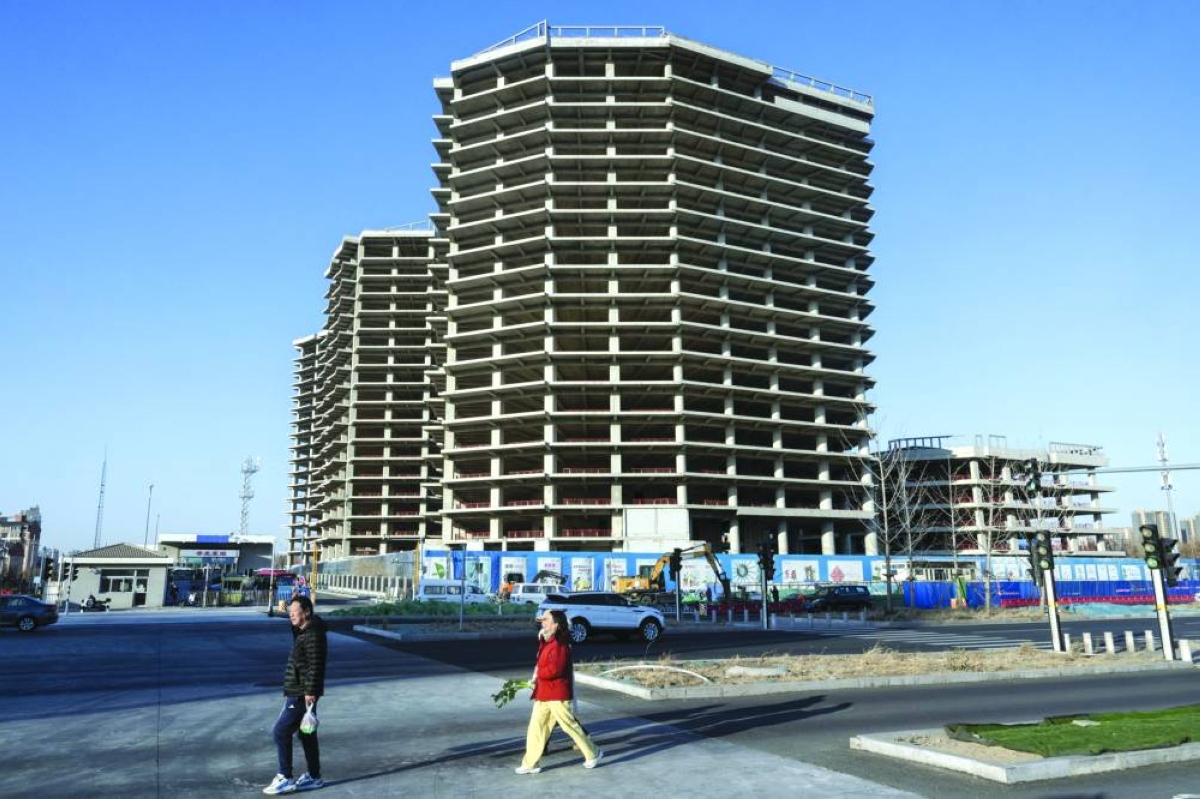

Once one of the country’s biggest growth drivers, China’s property market has been in a downward spiral for four years with no signs of abating. Real estate values continue to plummet, households in financial distress are being forced to sell properties, and apartment developers that racked up enormous debt on speculative projects are on the brink of collapse.There was some optimism that government measures to end the crisis had been working to reinvigorate the market, but in March, government-linked developer China Vanke Co reported a record 49.5bn yuan ($6.8bn) annual loss for 2024, showing just how deep the problems run. Then in August, property giant China Evergrande Group delisted from the Hong Kong stock exchange — making the shares effectively worthless — marking a grim milestone for the nation’s property sector.China is now considering further measures to revive its struggling property sector, particularly after new and resale homes recorded their steepest price declines in at least a year in October. The slump has heightened concerns that further weakening could destabilise the country’s financial system.What happened to Evergrande?Evergrande’s downfall is by far the biggest in a crisis that dragged down China’s economic growth and led to a record number of distressed builders.Founded in 1996 by Hui Ka Yan, Evergrande’s rapid expansion was from the outset fuelled by heavy borrowing. It became the most indebted borrower among its peers, with total liabilities reaching about $360bn at the end of 2021. For a time it was the country’s biggest developer by contracted sales and was worth more than $50bn in 2017 at its peak. Founder and Chairman Hui became Asia’s second-richest person. Over the years the company also invested in the electric vehicle industry and bought a local football club.In 2020, Beijing started to crack down on the property sector. The new measures put a cap on the developer’s borrowing capacity, effectively cutting off its lifeline from credit markets. Following failed restructuring attempts, Evergrande was given a winding-up order in Hong Kong in 2024. Later that year, a mainland Chinese court accepted a liquidation application filed against one of its major onshore units.After a long trading suspension, the Guangzhou-based company was formally delisted from the Hong Kong stock exchange on August 25. Evergrande still has two other units listed in Hong Kong: a property service provider — which liquidators are seeking to sell off — and an electric vehicle maker. The latter, China Evergrande New Energy Vehicle Group Ltd, has been suspended since April.How did some Chinese developers get into this mess?In 1998, China created a nationwide housing market after tightly restricting private sales for decades. Back then, only a third of its people lived in towns and cities. That’s risen to two-thirds, with the urban population expanding by 480mn. The exodus from the countryside represented a vast commercial opportunity for construction firms and developers.Money flooded into real estate as the emerging middle class leapt upon what was one of the few safe investments available, pushing home prices up sixfold over the 15 years ending in 2022. Local and regional authorities, which rely on sales of public land for a chunk of their revenue, encouraged the development boom. At its peak, the sector directly and indirectly accounted for about a quarter of domestic output and almost 80% of household assets. Estimates vary, but counting new and existing homes, plus inventory, the sector was worth about $52tn in 2019 — about twice the size of the US real estate market.The property craze was powered by debt as builders rushed to satisfy expected future demand. The boom encouraged speculative buying, with new homes pre-sold by developers who turned increasingly to foreign investors for funds. Opaque liabilities made it hard to assess credit risks. The speculation led to astronomical prices, with homes in boom cities such as Shenzhen becoming less affordable relative to local incomes than those in London or New York. In response, the government moved in 2020 to reduce the risk of a bubble and temper the inequality that unaffordable housing can create.Anxious to rein in the industry’s debts and fearful that serial defaults could ravage China’s financial system, officials began to squeeze new financing for developers and asked banks to slow the pace of mortgage lending. The government imposed stringent rules on debt ratios and cash holdings for developers that were called the “three red lines” by state-run media. The measures sparked a cash crunch for developers that was exacerbated by the impact of aggressive measures to contain Covid-19, such as the suspension of construction sites.Many developers were unable to adhere to the new rules as their finances were already stretched. In 2021, Evergrande defaulted on more than $300bn, triggering the beginning of China’s property crisis. Two more property giants defaulted — Sunac China Holdings Ltd in 2022 and Country Garden Holdings Co in 2023.How did the crackdown affect the property market?After years of insatiable demand from buyers, the market ground to a halt. In addition to the government’s lending restrictions, the economic shock of Covid lockdowns reinforced a culture of frugality, and a deteriorating job market meant people were suddenly facing layoffs and salary cuts.Property prices began to fall in 2022. In August 2024, the country recorded its steepest annual drop in property values in nine years. On top of the millions of square feet of unfinished apartments that indebted developers left to gather dust, the imbalance in supply and demand meant 400mn sq m of newly completed flats remained unsold as of May 2024.With household debt at a high of 145% of disposable income per capita at the end of 2023, homeowners are increasingly under financial pressure. The country’s residential mortgage delinquency ratio – which tracks overdue mortgage payments – jumped to the highest in four years as of late 2023. Some homeowners are being forced to sell their properties at a discounted rate, which is only exacerbating the problem.The weakness has continued to shake more cash-strapped developers. Mid-sized builder China South City Holdings Ltd was ordered to liquidate by Hong Kong’s High Court on Aug. 11 after a default more than a year ago. Hong Kong’s courts have issued at least eight wind-up orders for Chinese developers since the crisis began in 2021.How is the government trying to prop up the market?In 2022 authorities realised the rules to rein in the market had gone too far. Aiming to avoid a “Lehman moment” — when the failure of the US bank in 2008 sent shock waves through global markets — the government unveiled measures centred on boosting equity, bond and loan financing for developers to alleviate the liquidity crunch.**media[386054]**Developers were allowed to access more money from apartment pre-sales, the industry’s biggest source of funds, and 200bn yuan ($27bn) was advanced as special loans to complete stalled housing projects. The government tweaked financial rules, allowing the central bank to increase support for distressed developers and instructing banks to ensure growth in both residential mortgages and loans to developers in some areas.Since mid-2024, the government has cut borrowing costs on existing mortgages, relaxed buying curbs in big cities and lowered taxes on home purchases. It also trimmed purchasing costs for people seeking to upgrade dwellings in some big cities. In August 2025, Beijing authorities removed a cap to allow eligible families to buy an unlimited number of homes in outer suburban areas, and Shanghai and Shenzhen soon followed.Despite these measures, the property market continues to deteriorate. Bloomberg reported in November that Chinese policymakers were now weighing a new round of measures. Proposals include subsidising mortgage interest payments to lure back wary homebuyers into a market still in free fall. Other ideas being discussed include bigger income tax rebates for borrowers and lowering transaction fees on home sales.What’s at stake if China’s property market worsens?Government officials are clearly eager to bring the property crisis under control. They aim to limit the damage to developers and stem the bleeding to other vulnerable parts of the economy. This includes banks with heavy exposure to real estate; the construction industry, which employs 51mn people; and local governments that rely on land sales to developers to sustain their public spending.Chinese banks’ bad debt — loans they no longer expect to recover — hit a record 3.5tn yuan ($492bn) at the end of September. Fitch Ratings has warned the situation could deteriorate further in 2026 as households struggle to repay mortgages and other loans.A prolonged property slump could also deepen deflationary pressures. Former finance minister Lou Jiwei recently warned that households’ worsening outlook — driven by falling home values — will affect consumption levels and intensify price declines.According to economists at Morgan Stanley and Beijing-based think tank CF40, the property sector’s drag on inflation could even be greater than official data suggest. They argue that the methodology used to determine China’s official Consumer Price Index understates falling rents, and, by extension, the broader deflationary impact.