Japanese bonds used to have such low yields that they acted as a kind of anchor for the global debt market, adding downward pressure on government borrowing costs the world over. No longer.

The yield on 40-year Japanese bonds rocketed above 4% in mid-January, a first for any maturity of the nation’s sovereign debt in more than three decades. One reason is that the Bank of Japan, which owns more than half of the nation’s sovereign notes, has begun to scale back bond purchases. Another is the possibility of additional government bond sales to fund Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s tax-cutting plans.

The result has been months of uncharacteristic volatility, including several underwhelming auctions of government debt. Investors are on guard for the moves in Japanese bonds to spill over into the global bond market, where yields have been marching higher amid concerns over the ability of governments worldwide to rein in persistent budget deficits.

What’s (usually) the appeal of government bonds?

Government bonds are generally considered one of the safest assets to invest in because it’s deemed relatively unlikely that the issuer — a government — will go bankrupt. That’s because a government sets its own rules and can typically raise money when it needs to. Long-term bonds tend to offer investors relatively high yields for relatively low risk because the investor is agreeing to, and locking in, an interest rate for a significant period of time, like 20 or 40 years.

Japan’s $7.5tn bond market, in particular, has for decades been considered one of the most stable. But recently demand has been weak, for a few reasons, which has caused the price of bonds to fall, and yields to inversely rise.

Why has demand been weak?

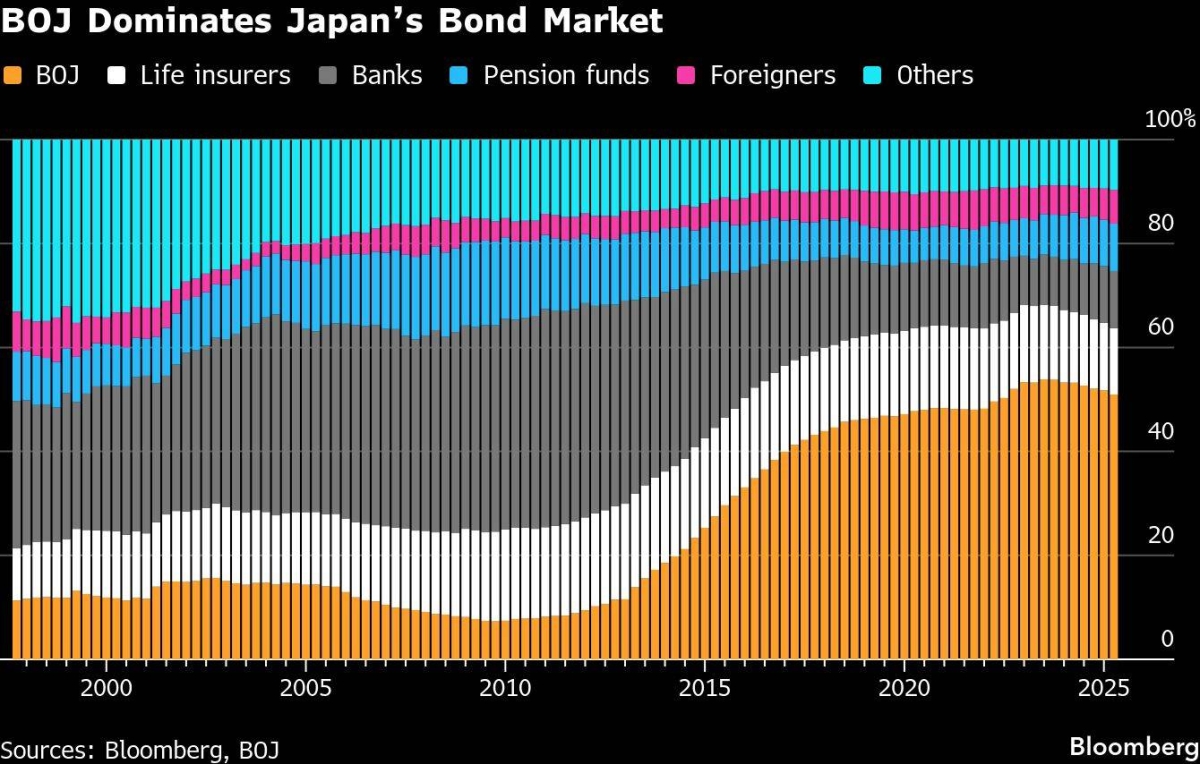

Japan’s central bank has long been the dominant buyer of Japanese government bonds. The country had, until recently, been in a cycle of deflation since the 1990s, known as the “Lost Decades.” Buying bonds, which allows the government to issue more debt and spend more as a result, had been part of the BoJ’s strategy to stimulate the economy.

But as Japan emerges from deflation and is no longer focused on bolstering the economy through bond purchases, the central bank has started to scale back its massive holdings, which hit a record high in November 2023. With the BoJ stepping back, there simply aren’t enough other buyers to absorb the supply, leaving demand weak.

What else is contributing to investor worries?

On November 21, the Japanese government approved a ¥21.3tn ($137bn) stimulus package — its biggest such spending plan since the pandemic. Takaichi has also called an early election for February 8 and promised to suspend Japan’s 8% sales tax on food items for two years if her coalition wins.

That has unnerved some investors because such measures typically require additional government borrowing, which means more bonds issued. Typically, when the supply of bonds increases, their price falls — and investors don’t want to be stuck with assets that could lose value.

Takaichi hasn’t clarified how she would pay for the tax cut, but the move is expected to cost roughly ¥5tn per year, according to the Finance Ministry. A strong showing at the polls would also likely embolden Takaichi to push ahead with further stimulus measures. The main opposition group, the Centrist Reform Alliance, has also pledged to abolish the food tax permanently, fuelling concerns about weaker fiscal discipline across the political spectrum.

At the same time, improving returns on Japanese debt may eventually put a floor under prices. Foreign buyers are taking advantage of the highest yields in years because hedging the yen back into their own currency can lock in additional returns. Overseas investors now account for roughly 65% of monthly cash transactions of Japanese bonds, up from 12% in 2009, Japan Securities Dealers Association data show.

But local institutions are still the biggest buyers of Japanese debt, and their appetite for buying more is being held back by heightened volatility.

What’s at stake if demand stays weak in 2026?

Persistently weak demand for bonds — and the higher yields that come with it — would increase borrowing costs across Japan, affecting the government, companies and households. There are already worries about Japan’s huge debt burden.

It also leaves the BoJ in a difficult position, as the central bank balances calls to keep borrowing costs low against the need to lift rates to control inflation.

For the nation’s life insurers, higher bond yields can mean huge paper losses on their domestic bond portfolios they have accumulated. Four of Japan’s biggest life insurers reported about $60bn of combined unrealised losses on their domestic bond holdings for the latest fiscal year, about four times the total a year earlier.

Are the government and central bank worried?

There are signs that both the central bank and government are uneasy about rising bond-market volatility.

After the intense bout of bond selling on January 20 — which spilled over into other markets — Japanese Finance Minister Satsuki Katayama urged market participants to “calm down.” US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said he had spoken with his Japanese counterpart amid the selloff, which he said had also affected the US Treasuries market.

Japan’s central bank has been wary even before the latest rout. BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda noted on December 9 that long-term bond yields were rising “at a somewhat rapid pace.” To avoid destabilising the market, the BOJ is planning to slow the pace of its retreat from the bond market. From April, it will cut monthly bond purchases by ¥200bn every quarter, instead of the current reduction of ¥400bn. Ueda also said the bank would be prepared to increase bond purchases in exceptional cases to stabilise the market if needed.

The government is also trying to avoid adding pressure to yields. To fund its stimulus package, it has opted to lean on short-term debt — boosting issuance of two- and five-year bonds by ¥300bn each — instead of relying on longer maturities.

Still, Japanese premier Takaichi has said it’s more important for her government to focus on economic growth rather than rising yields. She said it was impossible to isolate the impact of fiscal policy on yield moves.

What’s happening with bonds elsewhere around the world?

Many major markets around the world have been experiencing a rout in longer-dated bonds since US President Donald Trump unveiled his “Liberation Day” tariffs in April, which have heightened inflation risks and, in turn, pushed yields higher. Trump’s latest push to take over Greenland has also caused the price of US Treasuries to tumble.

Adding to the upward pressure on yields, traders are also increasingly betting that some central banks will slow or halt their monetary easing this year, further dampening demand for bonds beyond Japan.