Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell downplayed dissenting votes against Wednesday’s decision to lower interest rates again, but a slew of finer details from the meeting revealed just how divided the central bank has become.

Powell pushed through the quarter percentage point cut not only over the objection of a few voters. A much larger group of regional Fed bank presidents who participated in the debate but weren’t among this year’s voting roster also signalled they opposed the cut.

The fractures could foreshadow what’s to come in 2026, when a new chair may struggle even more than Powell to marshal consensus at the Fed.

“It’s very unusual. In my 10-plus years of being involved with the Fed, I haven’t seen this,” said Patrick Harker, who served as president of the Philadelphia Fed until his retirement in June.

Just two policymakers — Kansas City Fed President Jeff Schmid and Chicago’s Austan Goolsbee — formally dissented in favour of leaving rates unchanged. The other dissent came from Governor Stephen Miran, who continued to call for a larger rate reduction. The remaining protests came through different channels.

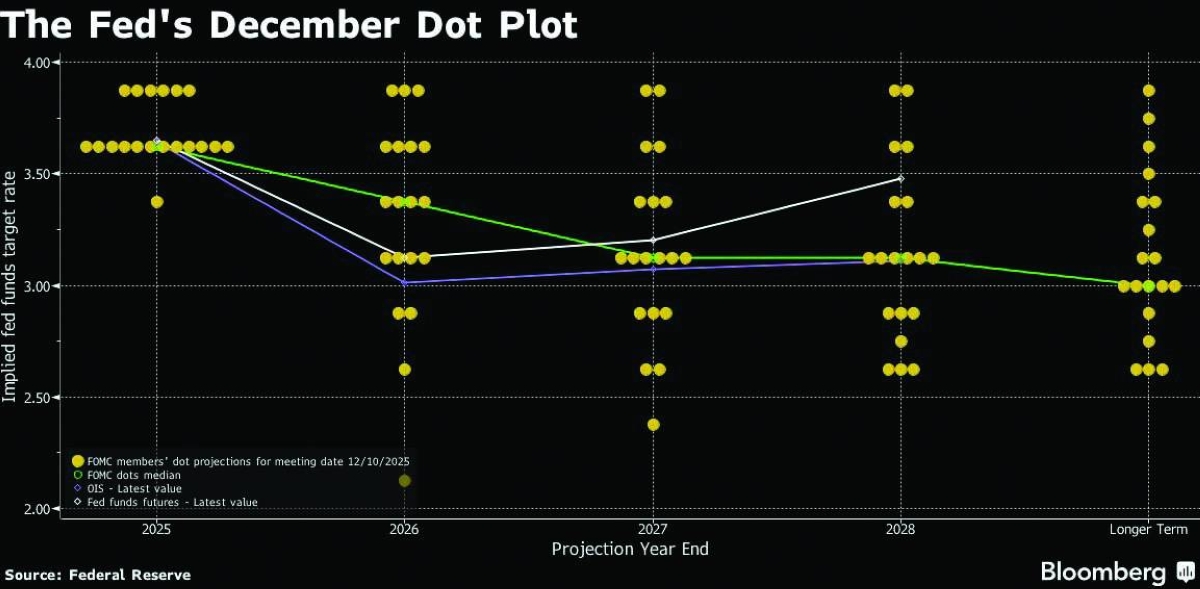

In quarterly rate projections the Fed published alongside the decision, six policymakers said the benchmark federal funds rate should end 2025 in a range of 3.75% to 4% — where it stood before Wednesday’s cut — suggesting they opposed the move.

Given that at least four and perhaps all of those six officials lacked a vote at the meeting, some Fed watchers have dubbed the high rate forecasts for 2025 as “silent dissents.”

“I would’ve been one of those silent dissents,” Harker said. “I think the cut is a mistake.”

There was yet another clue buried in the materials the Fed published Wednesday. In addition to the officials around the table, business leaders who comprise the boards of directors of the regional Fed banks also get to weigh in.

They submit recommendations for another short-term rate set by the Fed, which in practice always moves up and down with the central bank’s main benchmark.

Historically, that recommendation has served as a proxy for the bank president’s own preference. In this case, just four of the 12 regional banks requested a reduction, suggesting that eight presidents may have opposed the cut.

That vote shows that the inclination to hold rates steady was concentrated among the presidents. Those officials have often favoured higher interest rates than the members of the Fed’s Board of Governors in Washington, who are appointed by the White House and confirmed by the Senate.

Powell argued in his post-meeting press conference that the economy right now — with inflation still well above the Fed’s 2% target and the labour market showing signs of weakening — is one where disagreements are to be expected.

“A very large number of participants agree that risks are to the upside for unemployment and to the upside for inflation, so what do you do?” Powell said. “You’ve got one tool, you can’t do two things at once. It’s a very challenging situation.”

But with so many policymakers willing to make clear through their “silent” and formal dissents that they will stick to their guns, whomever President Donald Trump picks to replace Powell next year — including the frontrunner for the job, White House National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett — is likely to face challenges in corralling the Federal Open Market Committee.

“Chair Powell has been in the job for quite a long time and has a lot of respect on the FOMC,” said Calvin Tse, head of US strategy and economics at BNP Paribas. “If even under his leadership there are now three dissents, it is hard for me to see a new Fed chair that finds it easier to get unanimity among FOMC participants.”