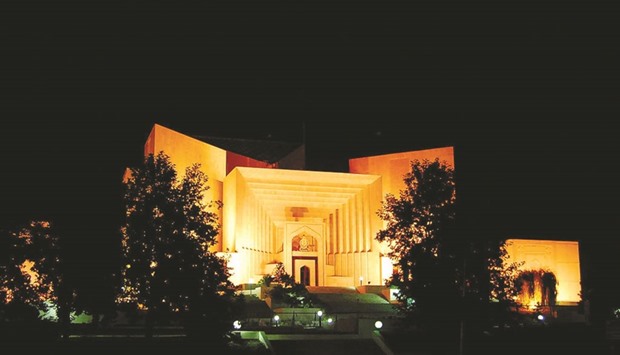

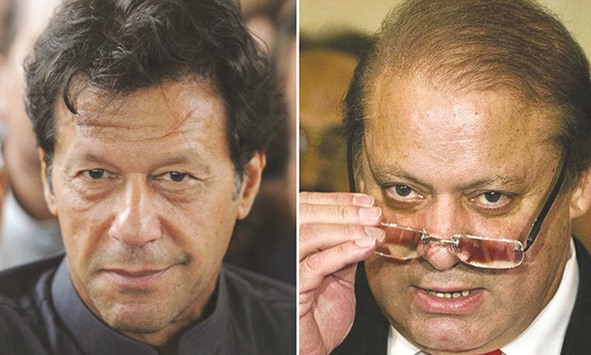

The wait to discern who remains abad (prospers) in Islamabad may now no longer be shrouded in the mysteries of a dark night Time was when critics would bemoan the pervasive drudgery of Islamabad – the stiff upper-lipped bureaucrats, the struggling government servants that mostly made up the citizenry, and a generally drab existence around an early-to-bed city, shorn as it was of life’s many splendours. It drew those unflattering descriptions about a place that was sarcastically assumed to be some distance removed from Pakistan – metaphorically speaking – producing one particularly, indicting comparison with Arlington cemetery and that, too, with a grave punch line – only twice as dead. Come democracy – following an air crash in 1988 that took care of General Zia-ul-Haq and his 11-year rule – and Islamabad came alive. Fast forward to today, the federal capital is still the place to reckon with, the place where all the shenanigans of power still play out and power itself resides, albeit with assuring stability. And if political power – which is the intended fulcrum of this piece – could be set aside for a moment, there isn’t a more lean, mean, green place to be in the whole of Pakistan. The jaw-droppingly beautiful capital that is home to the richest diversity of Pakistan (with the highest literacy rate and the youngest population), is a feast for sore eyes. That it is relatively quiet at the moment with the dead of winter approaching cannot however, detract from two very significant milestones lying in wait for one of the world’s hip political capitals. The two developments are pregnant with one chief corollary: what it portends for the prime minister. The first is the exit of the army chief – reckoned by hard knuckle opinion makers to be the real arbiter of power. But General Raheel Sharif is retiring next week, negating weeks and months of media speculation about either coerced or willing extension at the conclusion of his three-year term. The second relates to the ongoing Supreme Court hearing into the so-called Panama Papers case embroiling the children of the Prime Minister, who, because of his familial link is seen as a party to the case that could potentially, upend his rule in case of an unfavourable verdict. Significantly, the next hearing is after General Sharif has handed the baton to his successor. While the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) is relieved to see a smooth transition at the General Headquarters, it is also confident that the Panama case does not have merit and so will be quashed eventually. If Prime Minister Sharif indeed passes muster, he is expected to have smooth sailing into the 2018 polls. Pertinently, Project Democracy has moved, warts and all, into an era where increasingly it is the people’s vote and the judicial process combined that forms the bulwark against misdirected adventure. It wasn’t always thus. Contrast this with the past, for instance, when Sharif was still the chief executive, but had to watch his back thanks to a power troika where he trailed because apart from the army chief, he had to contend with an overbearing civilian president, too, who enjoyed sweeping powers to dismiss the government if he or she felt it was not being run in consonance with the constitution. It was quite a red herring – as Sharif’s predecessor, Benazir Bhutto, the-then prime minister, found out to her chagrin in 1990 – less than two years into her five-year stint. In 1993, Sharif struck an astonishingly defiant note after falling out against the very same president (Ghulam Ishaq Khan), who, had earlier sacked Benazir, famously thundering Mey Dictation Nahi Loonga (I won’t take dictation) – in a nationally televised address as he struggled to fend off the presidential octopus. Sharif is widely recognised as having freed himself from the shackles of the establishment that day. That slippery Article 58-2(b) was already notorious for its abuse by then, but this time, it was being fought over with contrasting jealousy: while Sharif wanted to apply the guillotine on it (by legislating against it), president Ghulam Ishaq Khan wanted to augment it. The air was thick with speculation about doom for the Sharif-led government – just like it had happened before with the ouster of the first Benazir Bhutto government in 1990. The ’93 episode was a tantalising affair. Amid the rising mercury in Islamabad’s political coliseum, the president struck a second successive time by dismissing the Sharif government, but it was subsequently, restored on appeal following a landmark Supreme Court decision that summer – the first time the highest judicial authority in the land had returned a favourable verdict for a civilian government. However, in a manifestation of how unpredictable power games were in Islamabad – with no small contribution from decision-makers in the garrison city, next door – both Sharif and Ishaq were forced to resign for failing to reconcile. Islamabad continued to be the hub of frenzied rumours in the following years with all talk in drawing rooms and out in the streets veering around who was doing what in or out of power – for the sake of power. Target-shooting continued to be the “in” political script with both Bhutto and Sharif being dismissed as prime minister one more time until an airborne General Parvez Musharraf, in a plane fast running out of fuel – or so the legend goes – decided to take matters in his hands. The two had fallen out over the Kargil conflict and in the obtaining battle of attrition, Sharif dismissed the General midair so-to-speak – a move that backfired tremendously. Backed by his commanders on the ground, Musharraf grabbed power in a bloodless coup, and later sent Sharif into exile following a foreign power-backed deal after the latter was dubiously convicted for hijacking the plane. The fateful drama on October 12, 1999 that day may have been enacted in Karachi but the fault lines lay in Islamabad. Sharif of course, would like to believe Rawalpindi was the epicentre of his misfortune. Unpredictability – for long the USB of Pakistani politics – is now returning to firmer, familiar grounds. Regardless of the white noise that the vibrant Pakistani electronic media creates, the wait to discern who remains abad (prospers) in Islamabad may now no longer be shrouded in the mysteries of a dark night. It is just as well that the retiring General Raheel Sharif – inarguably, the most popular army chief the country has ever had – and the Supreme Court have both contributed to solidifying the base of democracy. * The writer is Community Editor.

Kamran Rehmat

Kamran Rehmat is the Op-ed and Features Editor at Gulf Times. He has edited newspapers and magazines, and writes on a range of subjects from politics and sports to showbiz and culture. Widely read and travelled, he has a rich background in both print and electronic media.

Most Read Stories