Islamabad remains one of the world’s pre-eminent capitals for its geo-strategic gravitas. As one of a handful of declared nuclear powers alone means it ultimately, retains business interest for the world, but there is a question mark over how much Islamabad itself is doing to advance those strategic interests.

The long absence of a full-time foreign minister is not helping Islamabad’s cause at all and a belated move – reported by Reuters last week – to hire lobbyists in Washington after an eight-year hiatus to fill up the diplomacy gaps and influence movers-and-shakers on the DC circuit is an acknowledgment of how far have US-Pak ties slipped, of late.

The pinch was also felt more recently when Pakistan’s largely security driven foreign policy goals were gingerly pursued even as its rivals moved at a frenetic pace to convince any leftover skeptics around the world for a place in the coveted 48-nation Nuclear Suppliers Group.

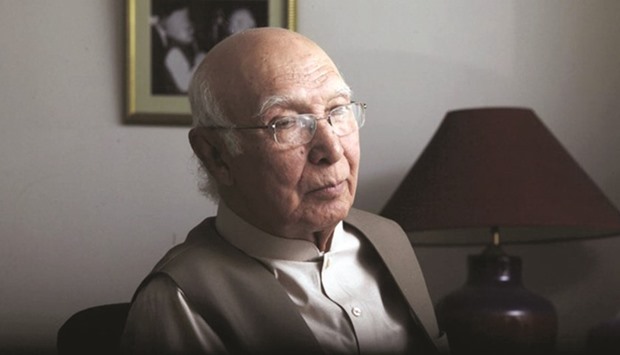

Sartaj Aziz, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s adviser on foreign affairs, did make a few calls to key world capitals, but it was never going to be enough, and remains unlikely to deliver the results that would be a decent bet, if say, Islamabad had a fulltime foreign minister manning the beat.

To be sure, there’s just no substitute for pro-active diplomacy that physically takes the top diplomat places, or have these foreign capitals reach out to — as opposed to making do with poor ad hoc cousins.

Trepidation is apparent in Sharif’s decision to not appoint a full time foreign minister in his third stint as prime minister.

There is an interesting background to this of course, but whether it is also justifiable is a moot point.

It stems from his uneasy relationship with the powerful security establishment during his previous two aborted terms.

But it is the relatively more recent episode pertaining to how Shah Mehmood Qureshi served as foreign minister at a crucial juncture in the last government of Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and his exit that so alarmed Sharif that he chose to keep the portfolio with himself upon assuming office in June 2013.

Qureshi refused to oblige his own party (PPP) – insiders suggest, after a nod from the security establishment – in the infamous Raymond Davis case.

Davis, a covert CIA contractor, was arrested by the authorities in Lahore after he killed two Pakistanis on mere suspicion they were chasing him.

The PPP government wanted the American released citing (unfounded) diplomatic immunity (after the Obama administration pressured Islamabad). The Qureshi dissent so annoyed Asif Zardari, the-then president and also PPP co-chairman, that he resorted to a cabinet reshuffle soon after a negotiated settlement - reportedly, between the Americans and the Pakistan military – led to Davis’ eventual release.

In the reshuffle, Qureshi was offered the agriculture ministry, which he reckoned to be beneath his “stature”, and therefore, declined.

Weeks later, Qureshi, who was a major contender for the PM’s slot when the Zardari-led PPP returned to power in 2008, quit the party and joined the emerging opposition Pakistan Tehrik-i-Insaf of firebrand cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan. He is now its vice-chairman.

This episode, more than anything else, insiders say, made Sharif wary and as a consequence, he decided beforehand that he would not be appointing a foreign minister.

Initially, Sharif also held the defence portfolio before reluctantly, handing over charge to his confidante Khawaja Asif in the winter of 2013.

Interestingly, Asif has found it difficult to endear himself to the security establishment because of his damning remarks against its role during General Parvez Musharraf’s reign.

The PM, however, does not seem to have the same level of trust when it comes to the foreign affairs portfolio.

What bewilders the pundits is that Sartaj Aziz has been a foreign minister – and before that the finance minister – in Sharif’s earlier two terms.

But this time, the veteran with a known ambitionless mien, was not even given a ticket to the Senate – upper house of Pakistan’s bilateral legislature – which would have constitutionally, enabled him to take the full minister’s charge.

In what appeared to be a further dilution of whatever powers Aziz would have enjoyed, if at all, Tariq Fatemi, another aide, was also appointed special assistant to the PM on foreign affairs, which predictably, sowed confusion and some heartburn to boot.

Riaz Khokhar, a much respected former foreign secretary, admitted in a subsequent piece on the subject that this move created confusion at the Foreign Office and even foreign delegates appeared clueless in whom to approach for what.

Even though Aziz did gain the upper hand in a match of wits with Fatemi, it still does not hold water since foreigners – in world capitals and delegates visiting Islamabad – remain sceptical of the pointman’s essential reach.

They cannot, of course, talk to the PM directly because of protocol even though they routinely make courtesy calls with the only leverage left with perhaps, a visiting US secretary of state.

With the PM also away for treatment and recuperation in Britain for weeks now – and rapid developments pregnant with far reaching repercussions at home, in the region and elsewhere on the globe – Islamabad was never more in need of a full time foreign minister as it is now.

The declining state of relations with the US, worrying border tensions with Afghanistan and the need for a viable diplomatic strategy to deal with the Nuclear Suppliers Group zeitgeist makes it incumbent upon Sharif to find a quick solution.

Reluctant half measures are no longer an option.

Any apprehensions surrounding a “Qureshi” encore are, in effect, meaningless and counterproductive because nothing can be achieved by creating a vacuum.

In fact, the “vacancy” makes it difficult for Sharif to direct and exercise steady control over foreign policy.

While hiring lobbyists in DC may help plug some of the gaps that have allowed disenchantment to grow manifold in Washington in the last few months – to speak of just one of the most critical bilaterals in the international arena; it does not, on its own, fill the void at the Foreign Office in Islamabad.

- The writer is Community Editor.

Underwhelming: Sartaz Aziz, who has been a foreign and finance minister in Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s two earlier terms, is now only adviser on foreign affairs.