One measure of borrowing by China’s local governments for infrastructure is on pace to hit a six-year low, as Beijing clamps down on risks in a strategy shift that calls into question its promise to stop an unprecedented investment slump.

Of the 4.4tn yuan ($626bn) quota for new local government special bond sales this year, around 3.02tn yuan is available for infrastructure projects — the lowest since 2019 — after the remaining 1.38tn yuan was used to repay loans, according to Bloomberg calculations based on official data. That puts the amount of bonds meant for investment in line to decrease for a second straight year.

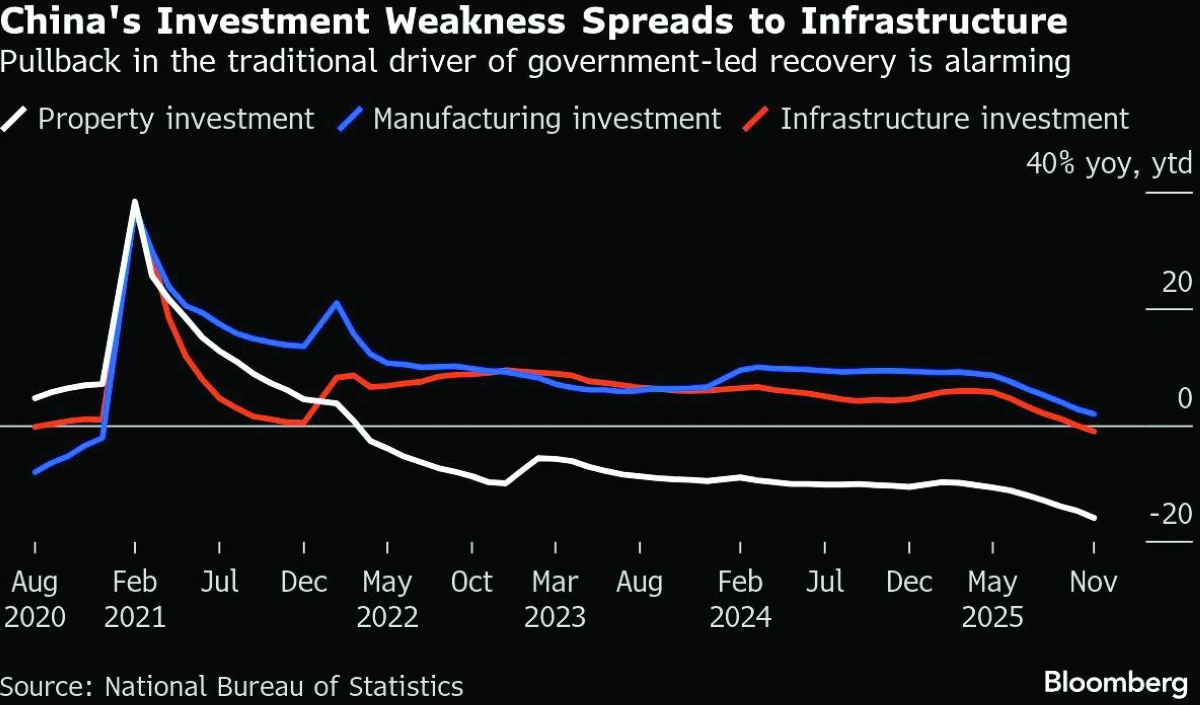

The restraint is ushering in a new economic era for China after decades of leaning on local governments to pour money into a network of roads, railways and industrial parks. Fixed-asset investment is on track for its first annual decline in data going back to 1998, after a crash made worse by the drought in funding for infrastructure.

“The contraction in FAI signals a break in China’s pattern of economic growth,” said Adam Wolfe, an economist at Absolute Strategy Research. “The restrictions on local government investment are likely to continue into 2026.”

While Wolfe expects investment to extend its drop in the first half, he said its trajectory later in the year is uncertain.

Behind the downturn is China’s campaign to rein in so-called hidden local debt, along with increasingly stringent rules for screening projects to ensure they generate sufficient returns. Coupled with stubbornly subdued business sentiment and a deepening property downturn, waning government funding support has fuelled a rapid pullback in overall capital spending in recent months.

Infrastructure investment contracted by about 12% on year in both October and November, according to Macquarie Group’s estimates based on official figures.

Top leaders have vowed to reverse the plunge next year. Yet Beijing’s focus on fiscal sustainability and what it deems as quality driven growth will likely leave local officials in a bind.

“A large part of the slump seems to be due to harder local government budget constraints and restrictions on their investment promotion activities,” Wolfe said. “This could shift the economy away from a model based on the regional competition to attract investment to one where central government macro control policies are more effective.”

China has been moving responsibilities for borrowing and spending from localities and putting them in the hands of the central government in recent years since it boasts a relatively healthier balance sheet.

The country’s top economic-planning agency has acknowledged that deeper factors are at play in putting a limit on investment.

In an article last week, the National Development and Reform Commission pointed to a rapidly aging population, slower urbanisation in some regions and a saturation of infrastructure. It also said manufacturers around the country face competition that’s increasingly undifferentiated with low value-added content.

The NDRC repeated President Xi Jinping’s definition of high-quality growth, whose criteria include profitable investment.

It listed a number of sectors where the government plans to channel capital spending, which range from utilities, public services and advanced manufacturing to low carbon development across energy, transport, construction and consumer industries.

As provinces shoulder less of a burden, officials have also pledged to increase the central government’s budget spending on projects and tap the quasi-fiscal financing tools at state-owned policy lenders to help achieve the goal of halting the investment drop next year.

But for special local bonds, they only promised to streamline the management of sectors receiving the funding, without hinting at a meaningful expansion in the quota.

Lynn Song, chief Greater China economist at ING Bank NV, said the call for stabilising investment reflected “genuine” concern among top leaders over the decline. That said, he expects the authorities will keep the taps of stimulus open just enough to counter any worse-than-expected headwinds for exports and ensure steady economic growth.

“We’ve seen pretty measured policy support in the last few years, and this is probably going to continue,” he said.

Even if the government ramps up spending, it’s unclear whether that will translate into stronger private investment, with uncertainty and weak confidence still weighing on activity, he said. The key question is whether any pickup is “only seen in public sector investment or if private investment can see a genuine recovery,” he added.