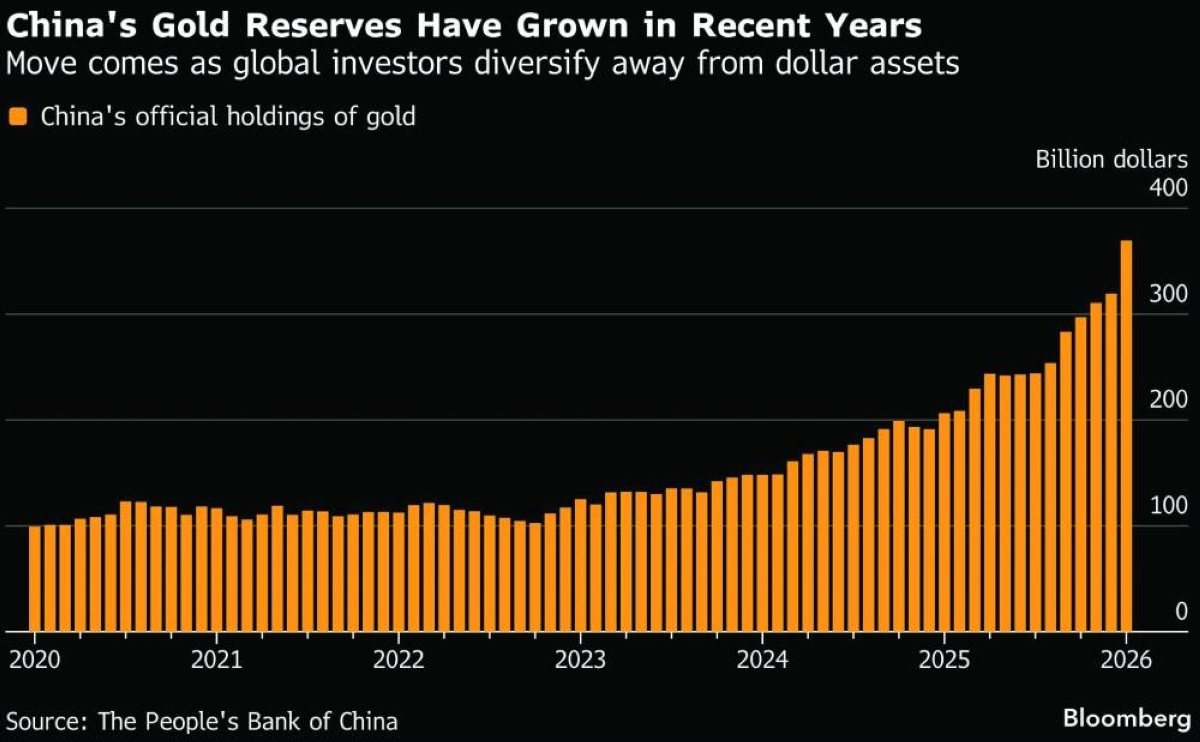

It’s the biggest pile of debt in the world — the $30tn US Treasuries market. It’s been built with the help of foreign central banks and investors, who have clamored to buy US government bonds through good times and bad. But what happens if their appetite wanes?China’s government has been steadily trimming its holdings over the past decade. While it’s still one of the biggest foreign owners of US Treasuries, its stockpile has almost halved since reaching a peak in 2013, dropping to $683bn in November, the lowest since 2008.Now, Beijing has urged Chinese banks to scale back their private holdings. Cutting those positions would reduce China’s reliance on the US — bolstering financial and national security, especially in times of tensions. But an overly rapid selloff in Treasuries might send the yuan higher and undermine China’s powerful export engine. What prompted Beijing’s guidance on US Treasuries?Chinese officials have framed the move as an effort to help banks generally reduce concentration risk and limit their exposure to market volatility. But the broader context points to Beijing’s strategic goal: reducing the country’s reliance on US assets as tensions persist over trade relations, technology and Taiwan.Policymakers are mindful of the precedent set in 2022, when the US and its allies froze about $300bn of Russia’s central bank reserves after the invasion of Ukraine. The worry is that if tensions were to escalate, the US could — in an extreme scenario — restrict access to China’s state and privately held dollar assets in a similar fashion. Are there disadvantages for China?China’s government has been building its gold stockpile for a decade and sharply accelerated purchases in 2025, making it one of the world’s largest official holders. But beyond bullion, China has few viable alternatives for investing its roughly $3.4tn in foreign-currency reserves — the world’s largest stash — and its domestic banks face the same problem.Other sovereign bond markets, for example those in Europe and Japan, are sizable but lack the depth and liquidity of the US Treasury market. And because countries such as Germany, France and Japan are US allies, it’s possible they would coordinate with Washington and impose similar sanctions if the US were to freeze China’s holdings. Other markets, such as equities or real estate, are either too risky or insufficiently liquid.There are also potential repercussions for China’s economy and balance sheet. A rapid, large-scale selloff would likely push Treasury prices down and US yields up, which could in turn weigh on the US dollar. A weaker dollar would make US exports more competitive and in turn dampen demand for Chinese goods — especially on top of tariffs imposed by US President Donald Trump. A falling dollar would also reduce the value of China’s remaining dollar-denominated assets.Finally, an overt move away from Treasuries could invite retaliation from the US, undercutting the financial stability China wants to preserve. Are there repercussions for the US?The initial dip in Treasury prices that followed Beijing’s call to curb banks’ holdings was brief, suggesting investors see limited repercussions for the market and are not expecting a sharp deterioration in China-US relations as a result.A more aggressive shift, however, could prove problematic. If China were to stop purchases altogether — or in an extreme scenario sold a large number of Treasuries — it would push bond prices lower and yields higher. That would mean increased borrowing costs across the US economy, including mortgage rates, corporate loans and government financing.Such a selloff could also prompt other countries to follow suit, potentially denting the dollar’s status as a global haven. That said, an outright dumping of Treasuries is widely viewed as unlikely. Why does China hold so much US debt in the first place?China’s massive stockpile of US debt isn’t simply an investment choice. It is largely a byproduct of its export-led economy. Due to the low cost of its products, the Asian nation has for decades sold far more goods to the US — such as toys, apparel and electronics — than it has bought. Those trade surpluses have generated a steady inflow of dollars.Chinese exporters can’t use dollars directly to pay wages or expand their businesses at home. While they can, in theory, convert dollars into yuan through the banking system, many exporters choose to keep their dollar earnings offshore and invest them in foreign securities, paying workers from their yuan revenues instead, because it’s more financially advantageous.For the central bank, holding a large reserve of Treasuries also serves a strategic purpose. It gives the People’s Bank of China firing power in a crisis, allowing it to support the yuan and stabilize local markets by selling their reserves when needed, just as it did in the aftermath of a shock devaluation in 2015. Are other countries or institutions selling their US Treasuries?Denmark’s AkademikerPension — a $25bn pension fund — said in January after US President Donald Trump threatened to acquire Greenland that it would sell the roughly $100mn of Treasuries it held. Dutch pension fund Stichting Pensioenfonds ABP says it’s reduced its exposure to US government bonds, cutting holdings by roughly €10bn to €19bn in the six months through September.Outside Europe, India’s holdings have fallen to a five-year low as authorities have acted to support the rupee and diversify its reserves. Brazil has also reduced its long-term Treasury holdings.Meanwhile, Japan, the UK and Canada each increased their holdings of Treasuries over the year through November 2025, according to official data.Overall, foreign holdings of Treasuries hit a record $9.4tn in November, but foreign investors now account for a smaller share of the total debt market than they have previously, reflecting the rapid growth of US government borrowing. Overseas investors now hold about 31% of Treasuries, down from roughly 50% at the beginning of 2015.

Sunday, February 15, 2026

|

Daily Newspaper published by GPPC Doha, Qatar.