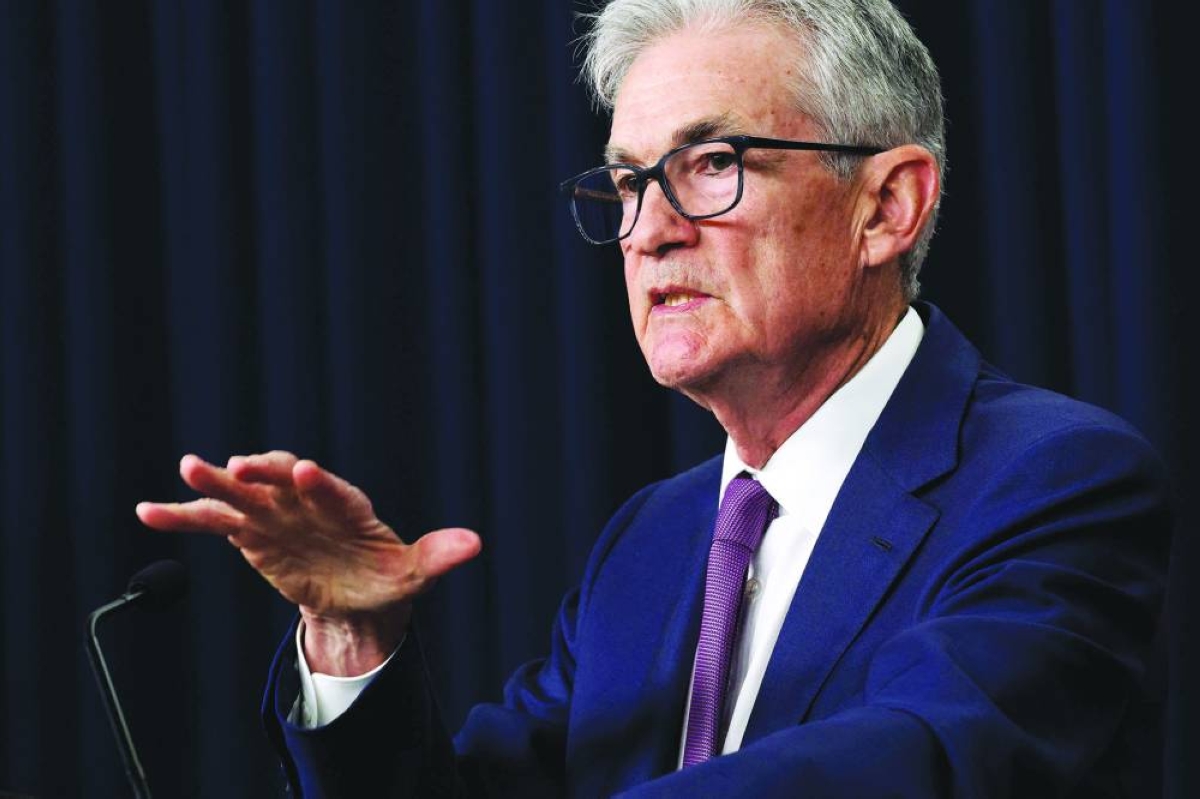

The Federal Reserve is expected to hold interest rates steady this week at a meeting overshadowed by a Trump administration criminal investigation of US central bank chief Jerome Powell, an evolving effort to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook, and the coming nomination of a successor to take over for Powell in May. Only three scheduled policy meetings remain in Powell's eight-year stint as the world's top central banker, but the typically smooth transition has become a potentially disruptive period.Powell faces the controversial decision of whether to stay on as a Fed governor under his successor, the Supreme Court may rule whether Cook becomes the first Fed governor removed by a president, and President Donald Trump's nominee to lead the central bank must convince US senators he won't be captive to Trump's demands. With so much in motion - and the Fed's independence at stake - the policy debate seems almost secondary, although analysts at this point largely expect the central bank's institutional guardrails to hold. Market-based inflation expectations and longer-term US bond yields have for now shown no widespread fear about the Fed's future."It's not possible to view the actions of the next Fed chair as separate from the economic environment or their ability to influence other FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) participants," said Tim Duy, chief US economist with SGH Macro Advisors.Indeed, whoever succeeds Powell will still need to convince other US central bank governors and the five voting Fed regional bank presidents of the need for any rate cuts, regardless of Trump's wishes."Trump will need greater turnover at the Fed to fully control the institution," Duy said. That process will take a major step forward when Trump announces, perhaps this week, his nominee to succeed Powell. The finalists include Trump economic adviser Kevin Hassett, Fed Governor Christopher Waller, former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh and BlackRock's chief bond investment manager, Rick Rieder.Trump has excoriated the Fed and Powell for failing to deliver the large rate cuts the president feels are necessary to boost the economy.The Fed's two-day meeting will conclude on Wednesday with policymakers expected to leave the central bank's benchmark interest rate on hold in the current 3.50-3.75% range. No new economic or policy projections are due, but investors at this point expect the Fed to pause further rate cuts until June, presumably under Powell's successor. Economic data since the last meeting in early December has shown little change in either labour market or inflation trends, offering scant impetus for guidance on when rates might fall again. Job growth has been weak, but the unemployment rate dipped in December to 4.4%, amid strong economic growth and consumer spending.The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index the Fed uses for its 2% inflation target was slightly higher than expected, at 2.8%, in November. Powell is scheduled to hold his usual post-meeting press conference on Wednesday, but his remarks may be less about the policy debate than what happened between meetings - including the receipt of a US Department of Justice subpoena and threatened criminal probe of the Fed chief, and Powell's response in an extraordinary video statement calling it part of Trump's campaign to pressure him and the central bank for rate cuts.A Supreme Court hearing followed last week concerning Trump's attempt to fire Cook. While the hearing lowered concerns about imminent risks to the Fed, with the justices appearing to lean towards leaving Cook in place, it also provided a reminder of Trump's stated hope of filling more seats on the Fed's Board of Governors than the normal rotation of terms would allow.As it stands, the president's nominee to succeed Powell would fill a seat that would have to be vacated by another Trump-appointed official, Governor Stephen Miran, who is on leave from the administration with a Fed term expiring this month. Barring a resignation or removal, the next opening would be Powell's seat. Powell, however, could remain a Fed governor for two more years after he steps down from the top central bank job, becoming what amounts to a swing vote on issues under the purview of the seven-member board beyond monetary policy.At last week's World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Trump recognised the dilemma."If he stays, he stays," Trump said of Powell in a CNBC interview. Trump also said he was near a decision on who to nominate to lead the Fed, but that the "problem is they change once they get the job." That ability to "change" - and make decisions that might go against the president's demands - is vital to the central bank's independence. It's why the coming court decision about Cook, the possibility of Powell continuing to serve, and the required Senate confirmation of the next Fed chief have garnered so much attention. The issues are intertwined.While the Trump administration argues that the decision to fire Cook is straightforward, with her alleged misstatements on mortgage documents disqualifying for a rate-setting policymaker in the president's view, it opened a broad debate at the Supreme Court during which both liberal and conservative justices affirmed the importance of the central bank's independence and questioned whether Trump's allegations warrant Cook's removal or the harm that would be caused by removing her. The threats against Powell, likewise, led to a global backlash, and several Republican senators indicated they'd hold up taking action on any Fed chief nomination until any investigation of Powell is resolved.The criminal probe jolted Powell from a largely passive posture towards Trump's years-long record of insults towards a more aggressive, public defence of the central bank as an institution. Powell maintained that stance when he decided to attend Cook's Supreme Court hearing last week and will have another chance to speak to the situation on Wednesday when he takes questions from reporters. With the Fed's benchmark rate around the level policymakers regard as neutral - the level at which activity is neither stimulated nor restricted - and the economy not clearly moving towards large job losses or faster inflation, "the near-term outlook is benign," Michael Pearce, chief US economist at Oxford Economics, said in a note last week.But "events outside the committee have the potential to shake up the path," as a new Fed chief takes over and particularly if the "small risk" of Cook being ousted is realised, Pearce said.Nevertheless, "our baseline is that the Fed will lower interest rates in June and September," and stop cutting with its benchmark rate still around 3%, an outlook that shows even Powell's successor may struggle to deliver the fast and deep rate cuts Trump demands, he said. "It would take a decisive weakening in labour market conditions for the Fed to deliver sooner and more aggressive rate cuts, which we think is unlikely," Pearce added.