A graduate of the National College of Arts, where he majored in painting (whilst also pursuing printmaking and sculpting), Ansari found the Midas touch in photography thanks to an innate ability to reflect on life and explore the hidden.

Based in Islamabad, Ansari, 31, likes to focus on places off the beaten path and passionately, pursued the unseen side of Pakistan as well as getting up, close and personal with both national icons and unsung heroes for the world to see — a result, he says, of a mission to change the negative portrayal of his country.

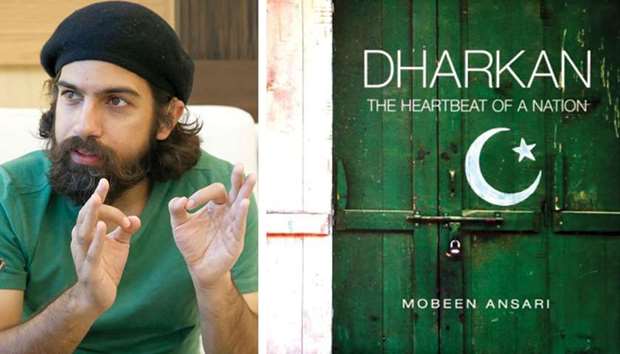

He has brought out two books — the third is in the works — and also produced an award-winning short film. But it is the subject matter that merits closer attention. Dharkan: The Heartbeat of a Nation, his first, is a collection of stunning portraits and landscapes. His second work entitled White in the Flag is an intimate look at the minorities of Pakistan. The third is a continuation of the Dharkan series. Hellhole, the short film he directed and produced, is an ode to the sanitary workers who go to work at great risk to their lives so that the citizenry could breathe easier.

Ansari, who, was in Doha last week as part of a bilateral photography exhibition with Haya al-Thani entitled Beautiful Pakistan, Amazing Qatar, has also exhibited his work in the US, Italy, China, India and Iraq.

Clad in a green tee, the two-time TED talk giver, who, has also produced work for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and featured in Newsweek to mention a few reputed names, opened up on his calling and the full gamut of photography during a special sitting with Gulf Times.

Tell us about your initiation into serious photography.

Art has always been an innate part of me; it has always been my passion. Since a very young age I’ve been very observant of my surroundings — mostly because of my hearing impairment. They say when God takes away something, He gives something in return and I believe that is something that has happened with me also. This observation has catapulted into my photography and sculpture.

It all began in 1998 when my family went to the Khunjerab Pass near the Pakistan-China border; I saw my father, who was an IT engineer, take pictures which he later stitched to form a panoramic view. This fascinated me and got me interested in photography. It must have been in the genes — both my grandmother and grandfather also did photography in the pre-Partition era. Part of the inspiration came from their work.

In my school days, my father bought a digital camera, which I would also take to school and take lots of pictures. This became an unsuspecting opportunity to bring out my inner passion for photography.

One day, a classmate of mine got into a fight over a girl and lost; he then retreated to the basketball court to vent his humiliation. Incidentally, I was at the court with my camera and thought to myself — I could either let the moment pass or give respond to the urge to capture the raw emotion. Impulsively, I did the latter and, in hindsight, developed a very strong connection with human nature.

What equipment is your first love? What are the essentials of photography as refined as yours?

Actually, all tools complement each other, but I have a liking for two lenses; one is the wide angle lens which I use extensively everywhere I go now and zoom as well. I got my first DSLR in 2005 and still use the same lens.

Having said that, let me say that it doesn’t matter how much you upgrade your equipment. What matters is how much you improve your aesthetics, and practice.

About essentials, well, this is something I keep asking myself. Every once in a while, I like to reinvent my style to break the monotony. There’s no one template I adhere to.

What particular genre appeals to you the most? How do you figure out the colour and black and white choices?

All of them have a different appeal; portrait because it allows me to understand the subject better — you need to follow the body language. It is like a silent communication. Landscape, on the other hand, is something you can never fall out of love. It has a charm of its own. You can’t really choose between the two; I have tried to, but really can’t!

As for choosing between colour and black and white, I’d have to quote Ted Grant, a veteran Canadian photojournalist, who famously said: “When you photograph people in colour, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in black and white, you photograph their souls!”

Having said that, there are of course, technical aspects involved. For me, the best time would be late afternoon when the light is good for a portrait. I like to use the iconic Rembrandt’s lighting techniques to give my portraits a painterly feel.

I love black and white and would prefer my subject to be near a window with light seeping in so that I have more control. It enables to hide flaws as well.

When did you first make a mark of your potential?

It was back in 2007 — my first year at the National College of Arts — when I did this portrait of a Bedouin on the outskirts of Islamabad for the Blue Chip magazine, which made it to the cover.

Difficult as it may be for an artist to pick, what would you reckon is your favourite image?

You know what the famous American graphic designer and painter Paula Scher said about “best work”? Well, she might have been marking out the guiding philosophy for me when she said: “I’m driven by the hope that I haven’t done my best work yet”. Am not shying away from picking, but that’s where I pretty much rest my case at the moment!

Give us an insight into your most famous work todate — Dharkan: The Heartbeat of a Nation.

I was in my final year at NCA and in the midst of this self-inquiry; questioning the very purpose of my being. I’d wish I could contribute to making my part of the world a better place. I thought of doing these images, which could hopefully, change the negative narrative about Pakistan. At the time, the security situation wasn’t so good. So I thought to myself — I must find the inspiration amongst her resilient people. I wanted to put Pakistanis from all shades into one spectrum and so got into photographing both the renowned and the unsung heroes. It wasn’t planned as a book, but eventually, it did take shape into one. It is a continuing series. There were portraits of 98 individuals in Dharkan-1 and so far, I’ve done 74 in Dharkan-2.

Talking of portraits, which is your forte, what kind of emotion do you think makes the close-up talk? Is there a template to make this work every single time?

The basic principle is respect; you’ve got to respect your subject, your craft. There is a general tendency to be commercially driven, but I think apart from the element of design and bringing harmony to the proceedings, it is about respecting the art.

You have made outstanding portraits of the who’s who of Pakistan. Who was the most intense, the most fun and the most difficult?

It was all pretty engaging though Shahid Afridi seemed a hard catch at the time with much toing and froing in a madcap race to catch him courtesy third party sources. Finally, when we did manage to get through to him directly, we were given just 4 minutes to get it over with! That was challenging to say the least. But he was busy as you would expect from someone of his stature.

As for fun, Behroze Sabzwari nailed it. Comical in an inimitable way, he reprised his famous character as Qabacha in that much followed mid-80s TV serial Tanhaiyaan. Another standout, for me, was (the folk musician) Arif Lohar, who brought out a very colourful visage in what was actually a black and white portrait!

There were others, who took a very long time to be persuaded to come forward for Dharkan — (the famous Vital Signs member and Coke Studio founder) Rohail Hyatt and (premier filmmaker) Shoaib Mansoor, for instance. I explained to them that this was not a commercial venture; rather, it was a celebration of iconic Pakistanis, and which would serve as a historic reference material for future generations.

During the course of your work, you must have met tens of dozens of people and trekked the country up and down. Who and what inspired you the most?

I have five favourite Pakistanis. (World renowned philanthropist) Abdul Sattar Edhi is on top of that list. No words I say can do justice to the kind of service he rendered for humankind.

Journalist Ardeshir Cowasjee was one of our bravest people. He abhorred privilege and would write on sensitive issues with uncompromising might. He was always on the right side of the common man. A gentleman, he would extend loans to students privately to help them and not take back when the time came.

Documentary filmmaker and rights activist Samar Minallah is another favourite. She is incredible. She has made taken up and documented issues related to the tribal areas, which is not everyone’s cup of tea. She has dealt with subjects like swara and vani — tribal customs that subjugate girls and women — with such compelling force that it led to the official banning of those anti-social practices.

Sayed Gul Kalash is an archaeologist, who is pursuing PhD in Kalasha — an indigenous and the smallest ethnoreligious community of Pakistan. She is working to preserve their identity, heritage and culture with such dedication.

Bapsi Sidwa, our accomplished novelist of Parsi descent, rounds up the list. Sidwa brings the country such honour. She is also my ‘adopted’ grandmother!

How was White in The Flag conceived? How much of an impact did it make compared to Dharkan?

Actually, the idea was conceived even before Dharkan during my forays into Karachi as a final year NCA student. It was done parallel to my work for Dharkan; sometimes I would do 15 shoots at a time to make it!

The response to both the works was more or less the same, but paradoxically, different too, because the audience was different. Dharkan was more personality based. White in the Flag has more insight in that it covers Pakistan’s rich minority landscape.

You have also directed and produced the short film Hellhole. How did it come about? Will you be doing more such fare in the near future?

It was a chance encounter with a sanitary worker (Akram Masih) whom I happened to see from a distance bob up and down a dirty manhole in Karachi back in 2010. There was dirt all over him as he went about his paces with muddy water splashing up and down and gas fumes renting the air. I’d never seen anything like it. For a paltry sum, he would undertake such a risky path to earn his bread so that people like us could move on with our lives. Later, I learnt that their life expectancy is 42-45 years. It all impacted me greatly.

Hellhole is a silent film; there are no dialogues in it, but it has this universal theme. Am currently, engaged in another short film, but on a different subject. It’s about birds.

Who has inspired you the most? Amongst your contemporaries, which one would you mark as noteworthy?

American photojournalists Steve McCurry — famous for his 1984 “Afghan Girl” portrait for the National Geographic — and Esther Bubley, who specialised in photography of ordinary people, in the era of illustrated magazines long before even our parents were born. Their art of portraiture is something I’ve tried to follow. Esther’s use of light and images of railway stations were incredible. She did intimate work on the black community.

Amongst contemporaries, photojournalists Haseeb Amjad, Danial Shah, who is also a filmmaker, and Khaula Jamil (best known for her work for the ‘Humans of Karachi’) are doing fantastic work. It’s a coincidence that all of them belong to Karachi.

Has it all become too convenient to live by smartphone photography? Do you think with all its user friendly tools, it is eating into the art?

We have to remember it is the age of social media, where a certain culture of ‘likes’ dominates, which sort of prevents critique. Yes, the tools are better today, but I think what is lacking is constructive criticism in terms of feedback. I, too, upload pictures to even flickr — which once upon a time was the go-to platform — for feedback. I still talk to my seniors, asking them if, and where, I’m going wrong and how to improve.

There are still people who do photography the old-fashioned way and there is still a line between professionals and hobbyists. Having said that, I wouldn’t really blame smartphone photography, for, there are enthusiasts who do a great job of it, too — sometimes even better than us. Even I do it, but very occasionally. Sometimes it just depends on circumstances where you have to capture a fleeting moment — at a moment’s notice. Smartphone photography, that way, gives you that flexibility.

What advice would you give aspiring photographers — to ‘real’ photographers, not their smartphone cousins?

(Laughs) to everybody, really. Passion is the key. Always think you still have to create your best work. Always. Because that keeps you driven. The moment you think your best work is done, you lose motivation — as is true of life itself. Keep an open eye and an open mind; do not be afraid to express yourself. Most important of all — this is something I’ve learnt in the last two months or so — Don’t be afraid of your inner child. Always be curious; you know how a child keeps raising questions. You have to keep asking these questions!