There have been films and films and films on sports. So Ali Abbas Zafar’s Sultan, which captures Salman Khan’s wrestling bout in the mud-pits of Haryana with all the gloss and glamour of a Bollywood biggie, is neither novel nor captivating in a touch-my-heart sort of way.

For me, the most marvellous sports movie was — and still is — Tigmanshu Dhulia’s Paan Singh Tomar, where Irrfan Khan gives a brilliant performance as a champion steeple-chase runner, who devastated by the government’s heartless attitude towards him, turns into a “baghi” or rebel.

As a runner-up on my list of sports films is the Shahrukh Khan starrer, Chak De India!, a great piece of work by Shimit Amin — who explores religious bigotry through the game of women’s hockey. Khan essays a fallen player, who becomes a coach of the Indian women’s hockey team, and propels it towards a win in the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

Madhavan’s bi-lingual Irudhi Suttru (in Tamil and Hindi) was also about a fallen hero, a boxer, who later becomes a coach, pushing a fiery fisherwoman in the slums of Chennai to spectacular heights. But unlike Chak De India!, Irudhi Suttru by Sudha Kongara Prasad, weaves into its narrative a love story, beautifully restrained.

So, if one were to talk about a pure sports movie, Paan Singh Tomar will pip the rest at the winning post, with Shah Rukh’s Khan’s hockey adventure coming a close second.

It is in this context, that I have serious reservations against Sultan — which turns out to be a typical Bollywood bonanza with song and dance and sobbing and romance. Undoubtedly, there is a lot of do-or-die wrestling in the film wrestling which Salman Khan’s Sultan gets down to — first to impress and win over Aarfa (Anushka Sharma), a champion wrestler herself, and later to pacify an angry wife, who cannot forgive her husband for having gone away for a championship during her child birth. The baby with a rare blood group dies of complications, which could have been tackled had it got a transfusion in time. The father, whose blood group tallied with that of his child, could have saved his child if only he had been around.

Zafar tries to say a lot many things in his movie — female foeticide, male arrogance and so on — turning what might have been a simple sports film into a ragbag of syrupy sentimentality and ponderous predictability. It is given that the hero in such supersize Bollywood movie has to win hands down — even when he is beaten and brutalised literally out of shape.

Of course in India, cinema superstars have to win on screen, and off it, they have to win as well. They can do nothing wrong. The aura around them, and the halo are so powerful that they blind their fans to terrible follies. Look at the way Sultan has been pounding the box-office with a bountiful of bucks — over Rs100 crores in the first three days of its opening, and still counting. And in all this delirious merriment, when Khan’s fans are crowning him with the title of Sultan, the 50-year-old actor’s several misdemeanours will be brushed well below the carpet.

Khan has been for a long, long time Bollywood’s bad boy — since those early days when he was accused of physically brutalising his then girlfriend, Aishwarya Rai, to the most recent times, when he compared himself to a rape victim. He said he felt like one every time he finished a backbreaking schedule of Sultan. Khan’s words were met with horror by women’s groups, who wanted him punished.

But punishment is something that Sultan Salman has been evading with a cunning finesse that goes beyond the realm of the absurd. In 2002, Khan in a supposedly inebriated state ran his luxury car over pavement dwellers in Mumbai, killing one and injuring four. This accident has by now begun to look like a piece of jigsaw puzzle — the parts appearing and disappearing like magic.

Many things happened in the legal case which followed the tragedy. The police bodyguard, Ravindra Patil, who was on duty with Khan on the fateful night did reportedly tell the court that the actor was at the wheel and that he was drunk. Later, Patil was under immense pressure to change his version of the mishap. It is not actually clear whether he did do, but he was suspended from the police force, and subsequently died of tuberculosis.

Khan has also been accused of poaching black buck in Rajasthan’s Bishnoi territory. The animal is part of India’s endangered species — and is also considered sacred by the community.

If Khan has been successfully playing hide-and-seek with the law, he has also been working hard on the cinema front. Probably to clean up his image, he has been choosing characters who are simply endearing. In Bajrangi Bhaijaan, he plays a devoutly pious man who restores a small Pakistani girl — who gets lost in India — to her parents. In Sultan, he is the wrestler who earns his country honour and respect. Earlier, he had essayed a fearlessly honest cop in Dabangg and Dabangg 2.

And in the kind of immense euphoria that Khan creates through his work, all his “misdeeds” are not just forgotten, but seemingly forgiven as well.

I still remember how a young Palestinian girl, who during a group lunch at Cannes some years ago, literally flew into a rage and might have just about knocked me out, when I had criticised Salman’s alleged misdeeds. She vowed to travel to India to try and instil some sense into my head.

But what I would like to tell her in the words of blogger Honey Mehta: “To err is human, but to err and get away with it every time is Salman Khan.” Indeed, how true!

*Gautaman Bhaskaran has been writing on Indian and world cinema for over three decades, and may be e-mailed at [email protected]

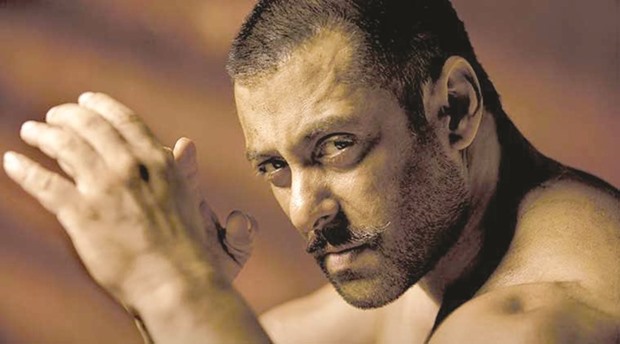

RECORD BREAKING: Salman Khan’s latest film has grossed more than INR100 crore in just three days.