Chinese companies, with ever more cash tied up in stocks and unpaid bills, are facing their tightest liquidity crunch in a decade, according to a Reuters analysis, forcing some into more costly and less secure borrowing to stay afloat.

The analysis of Chinese listed companies that have reported 2015 earnings shows it takes them almost 170 days to turn working capital – broadly the net amount tied up in stocks and bills payable and receivable – into cash.

For the 141 of the companies that have been around for at least a decade, the figure is 130 days, compared with roughly one month 10 years ago, and both the amount clients owe them and the amount they owe suppliers are at the highest level since at least 2006.

The figures demonstrate the growing strains on Chinese companies as banks, chastened by a doubling in bad loans last year, become increasingly reluctant to lend into China’s slowing economy.

Banks prefer to lend to state-owned enterprises, rather than the smaller businesses that provide 80% of urban employment and 60% of GDP, so rate cuts and monetary easing steps from China’s central bank are not making life much easier for them.

“The last two years, people often say things are okay, but then don’t pay up,” said a manager at Shandong Wansheng Stainless Steel in eastern China, who gave his surname as Wang.

“It has a big impact; it means we don’t have enough capital and have to find other channels.”

The squeeze is particularly acute for small businesses like Gangye Machinery in Suzhou, eastern China, which have less clout with suppliers and lenders alike.

Pan Zhengqiang, who owns the firm, said his clients are taking two to three months to pay, up from one to two months a year ago, and his bills are piling up and his staff still need paying.

He wants a bank loan, but says the banks have too many conditions for people like him, and they always find a reason to turn him down.

“If I can’t get a loan there, then I have to go to relatives or friends,” said Pan. “If I can’t even borrow from them, then the only options left are microcredit firms and loan sharks.”

The unmet needs of people like Wang and Pan are fuelling a boom in alternative lending such as online loans brokered on peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms, in a country where regulators are already fretting about the hidden risks in its sprawling shadow banking industry.

P2P loans shot up in the first two months of the year to hit 243bn yuan ($37bn), versus 69bn yuan for the same period in 2015.

They quadrupled in 2015 to 982bn yuan, according to industry data provider Wangdaizhijia.

P2P loans are more costly than bank loans, but they are quick, and speed can be critical to businessmen facing a cashflow crunch.

“They run a business and don’t need to wait for three months before you are able to tell them that they are qualified (for a loan) or not,” said Soul Htite, chief executive of online lender Dianrong.com, echoing complaints from small firms who say they struggle to borrow through regular channels.

Dianrong.com now has 2,700 employees, and its loan volumes grew over tenfold last year against 2014, Htite said.

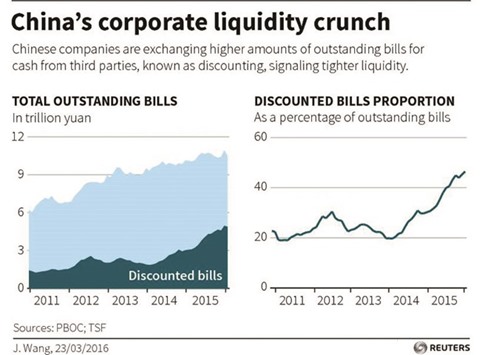

Businesses are also increasingly resorting to selling their unpaid bills to a third party, suffering a discount on the face value of the debt but getting immediate access to cash.

Discounted bills now amount to 46% of the total, up from 20% at the end of 2013, according to research firm CreditSights – its highest level since monthly data began in 2011.

With China’s growth set to slow further from its 25-year low in 2015, and wary consumers paring back their spending, the cash crunch for businesses can only get worse.

GMM Nonstick Coatings, which has a plant in Guangdong province making coatings for rice cookers and saucepans, said its China sales, which account for 10 to 20% of its total, are down 15% so far in 2016.

“When consumer (appetite) starts to dip, stuff isn’t moving off the retailer’s shelf,” said CEO Ravin Gandhi.

“As soon as the retailer sees that, they take their foot off the gas pedal for their suppliers.”

That is already having consequences for GMM’s trade debtors; it is now imposing a 45-day payment period on domestic buyers, down from 60 days at the end of 2015.

“It ripples all the way down the line,” said Gandhi.

..