Reuters

Benchmark 10-year German government borrowing costs have never been lower, and while the prospect of them dwindling to zero and even below is highly unlikely, it is no longer inconceivable.

Slowing economic growth and a seemingly relentless decline in inflation across the eurozone, including Germany, has spurred buying of Bunds, meaning Berlin can now borrow for 10 years at less than 1% compared with 2% at the start of the year.

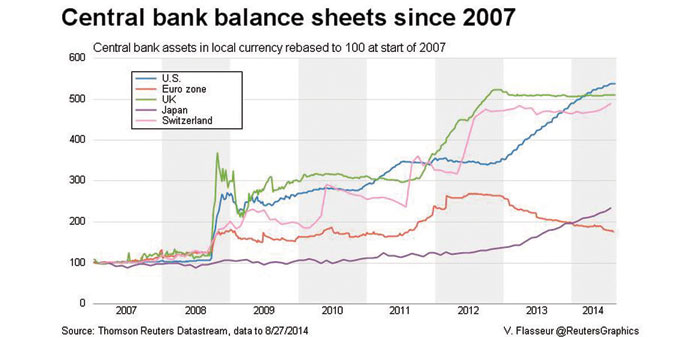

Expectations the European Central Bank will eventually succumb to quantitative easing (QE) - buying large amounts of bonds to pump money into the currency union’s limping economy – have pushed up demand from investors even as yields have dipped.

In a landmark speech, ECB President Mario Draghi highlighted a “significant” fall in eurozone inflation expectations this month, dropping his strongest hint yet that a QE programme is possible over the next year.

This has strengthened already pertinent comparisons with Switzerland and Japan, which have battled deflation and experienced ultra-low yields for prolonged periods recently -raising the question: Just how low can the Bund yield go?

Chief Citi rates strategist Alessandro Tentori and his team last week slashed their 10-year Bund yield forecast to 0.75% at the end of the year, from last month’s prediction of 1.45%.

“There’s no impediment for yields going even lower,” Tentori said. “It’s technically conceivable to have a 10-year rate at zero or below zero, but the scenarios that underlie that would be extreme.”

Draghi’s comments pushed down bond yields across the eurozone, with returns on 10-year German paper dropping to 0.926% and on two-year German bonds, already below zero, as low as -0.045%.

Two-year yields have gone negative in five eurozone countries this month, and Switzerland’s five-year yield went negative in 2012. But for a 10-year yield on a developed economy’s government bond to do the same would be unprecedented.

Japan and Switzerland have long struggled with falling prices and a strong exchange rate, a combination that can put a permanent dampener on economic growth. Comparisons with Germany are a useful, if imperfect, guide to how Bunds might trade.

The yield on 10-year Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) troughed at around 44 basis points, or 0.44%, in June 2003, while the comparable Swiss yield’s low was around 37 basis points in late 2012.

One of Japan’s main weapons was full-scale QE, with the Bank of Japan flooding banks with cash and pushing policy and market rates to zero in order to boost lending and growth.

Simultaneously, the government embarked on the biggest spending spree in modern history, sending the country’s debt soaring above 200% of gross domestic product. But despite the ballooning debt there has always been solid demand for JGBs.

Although Germany’s debt profile is much healthier - debt is at 77% of GDP and falling - many of the malign economic forces that Japan battled for so long look to be converging on Europe’s dominant economy.

It unexpectedly contracted in the second quarter, the growth outlook has dimmed, and inflation is falling alarmingly fast.

Some measures suggest investors expect German inflation to be lower than Japan’s over the long term. Ten-year German breakevens, the yield gap between conventional and inflation-linked bonds, at 1.18%, are lower than Japan’s 1.22%. Two-year German breakevens are currently negative.

And the five-year, five-year forward breakeven rate - the ECB’s preferred measure of the inflation outlook, which now shows roughly where investors expect forecasts of inflation for 2024 to be in 2019 - has tumbled.

This rate shed almost 20 basis points in August, and traders say it is close to its 2010 record lows of around 1.90%.

“Inflation expectations ... have been dropping like a stone,” said Jussi Hiljanen, chief fixed income strategist at SEB. “Downside pressure in yields will continue.” Annual eurozone inflation was 0.4% in July and data is expected to show it was 0.3% in August, falling further below the ECB’s target of just under 2%.

In respect of its status as a safe haven for investors, Germany compares more closely with Switzerland.

The Swiss franc firmed sharply as the financial crisis struck, prompting the Swiss National Bank to spend hundreds of billions intervening in the market to protect a 1.20-per-euro ceiling for the local currency.

The eurozone crisis also sent safe-haven flows into German bonds. And while investors have since rediscovered their zest for Spanish and Italian bonds, any renewed tensions will be sure to stoke demand for the bloc’s safest market of all, Germany.