Airbusô finishedô lastô yearô asô theô worldãsô largestô aircraftô manufacturerô byô deliveries.ô Boeing,ô however,ô hasô reclaimedô somethingô itô hasô notô heldô forô mostô ofô theô pastô decade:ô Theô leadô inô annualô orders.ô Thatô splitô tellsô youô almostô everythingô youô needô toô knowô aboutô whereô theô duopolyô standsô atô theô endô atô theô startô ofô 2026,ô andô whereô theô realô contestô isô nowô beingô fought.

Onô oneô sideô sitsô Airbus,ô deliveringô aircraftô atô scaleô inô aô supply-constrainedô world.ô Onô theô otherô sitsô Boeing,ô stillô workingô throughô theô consequencesô ofô yearsô ofô industrialô andô regulatoryô disruption,ô butô increasinglyô successfulô atô sellingô theô future.ô Theô divergenceô betweenô deliveriesô andô ordersô isô notô aô contradiction.ô Itô isô theô definingô featureô ofô theô marketô rightô now.

Byô year-end,ô Airbusô deliveredô 793ô commercialô aircraft,ô narrowlyô exceedingô aô revisedô targetô afterô acknowledgingô itô couldô noô longerô reachô itsô earlierô ambitionô ofô aroundô 820.ô Boeing,ô meanwhile,ô deliveredô 600ô aircraft,ô itsô highestô annualô totalô sinceô 2018ô andô aô materialô improvementô onô recentô years.ô Theô deliveryô gapô remainsô wide,ô butô theô directionô ofô travelô matters.ô Boeingãsô outputô isô risingô fromô aô lowô base,ô whileô Airbusô isô grapplingô withô theô limitsô ofô aô stretchedô supplyô chain.

Whereô Boeingô surprisedô theô marketô wasô onô theô salesô side.ô Theô USô manufacturerô securedô 1,075ô grossô ordersô afterô cancellationsô andô conversions,ô edgingô pastô Airbus,ô whichô reportedô 1,000ô grossô ordersô forô theô year.ô Itô isô theô firstô timeô thisô decadeô thatô Boeingô hasô outsoldô itsô Europeanô rivalô onô anô annualô basis.ô Theô symbolismô isô significant,ô evenô ifô theô underlyingô driversô areô moreô complexô thanô aô simpleô commercialô resurgence.

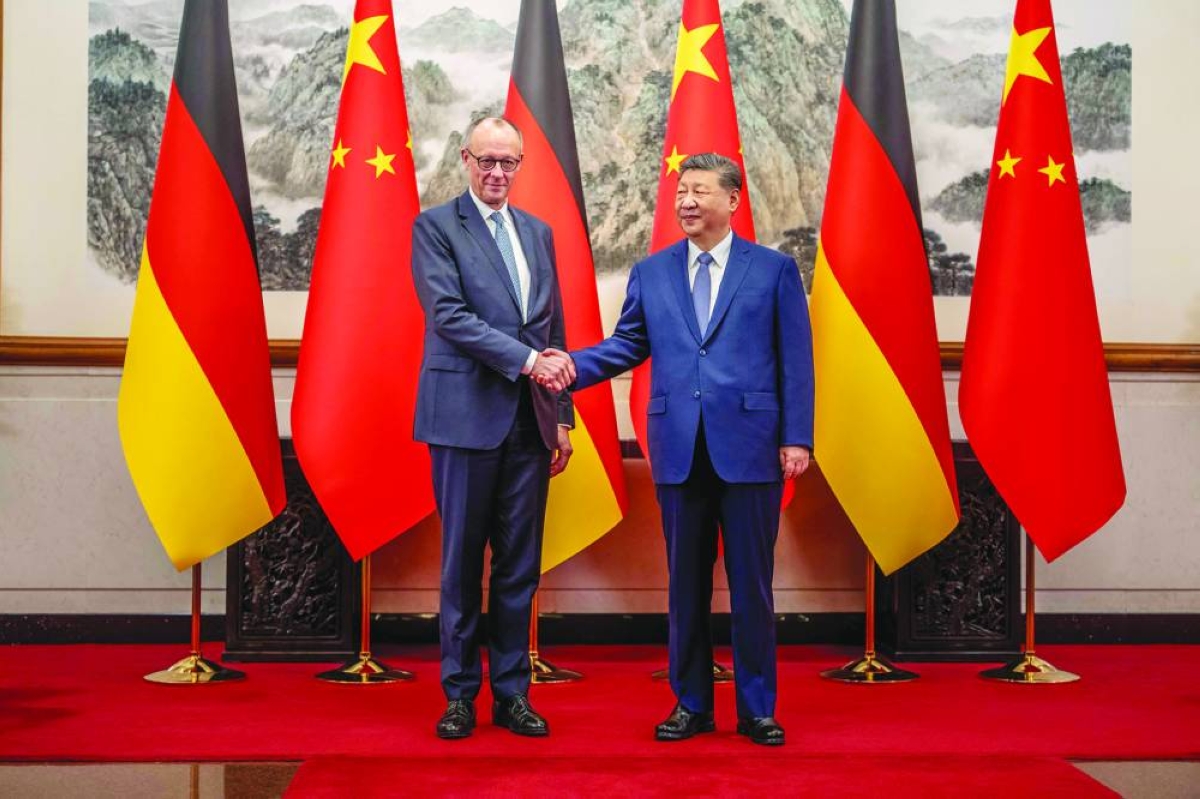

Politicsô playedô aô role,ô andô fewô inô theô industryô disputeô that.ô Governmentsô andô flagô carriersô placedô largeô ordersô forô Americanô aircraftô duringô aô yearô markedô byô renewedô tradeô tensionsô andô theô re-emergenceô ofô transactionalô diplomacy.ô Boeingô benefitedô directlyô fromô thatô environment.ô Ordersô fromô Qatarô Airways,ô Japan,ô andô Southô Koreaô wereô announcedô inô closeô proximityô toô high-levelô politicalô engagementô withô Washington.ô Christianô Scherer,ô Airbusãô outgoingô headô ofô commercialô aircraft,ô acknowledgedô publiclyô thatô Boeingô hadô enjoyedô ãpoliticalô backingã.ô Heô wasô statingô anô obviousô realityô ratherô thanô lodgingô aô complaint.

Theô Qatarô Airwaysô orderô aloneô underlinedô theô scaleô ofô thatô political-commercialô alignment.ô Theô commitmentô forô upô toô 210ô widebodyô aircraft,ô includingô largeô numbersô ofô 787ô Dreamlinersô andô 777Xô jets,ô isô oneô ofô theô biggestô widebodyô dealsô everô signed.ô Japanãsô agreementô toô purchaseô 100ô Boeingô aircraftô asô partô ofô aô broaderô tradeô arrangement,ô andô Koreanô Airãsô recordô orderô announcedô shortlyô afterô presidentialô talksô inô Washington,ô followedô theô sameô pattern.ô Theseô wereô notô marginalô campaigns.ô Theyô reshapedô Boeingãsô backlogô almostô overnight.

Atô theô sameô time,ô Boeingãsô recoveryô isô notô purelyô diplomatic.ô Underô Kellyô Ortberg,ô whoô tookô overô asô chiefô executiveô inô Augustô 2024,ô theô companyô hasô stabilisedô itsô finances,ô improvedô labourô relations,ô andô broughtô aô measureô ofô predictabilityô backô toô theô 737ô Maxô programme.ô Theô Federalô Aviationô Administrationãsô decisionô toô restoreô Boeingãsô abilityô toô issueô itsô ownô airworthinessô certificatesô forô theô 737ô Maxô andô 787ô Dreamlinerô markedô aô turningô point.ô Theô subsequentô increaseô inô theô Maxô productionô capô fromô 38ô toô 42ô aircraftô perô monthô sentô aô clearô signalô thatô regulatoryô confidence,ô whileô cautious,ô isô rebuilding.

Boeingãsô long-awaitedô acquisitionô ofô Spiritô AeroSystemsô hasô alsoô changedô theô industrialô equation.ô Bringingô aô criticalô supplierô backô insideô theô groupô wasô notô cheap,ô butô itô addressedô aô structuralô vulnerabilityô thatô hadô becomeô impossibleô toô ignore,ô particularlyô afterô theô Alaskaô Airlinesô doorô plugô failureô inô earlyô 2024.ô Theô messageô toô customersô andô regulatorsô wasô straightforward:ô Boeingô understandsô thatô controlô ofô qualityô cannotô beô outsourced.

Airbus,ô forô itsô part,ô remainsô theô strongerô industrialô machine.ô Deliveriesô continueô toô flow,ô particularlyô acrossô theô A320ô family,ô whichô accountedô forô moreô thanô 600ô aircraftô lastô year.ô Theô A350ô programmeô hasô alsoô gainedô momentumô asô supplyô chainô pressuresô eased,ô andô widebodyô productionô becameô moreô predictable.ô Yetô Airbusãô performanceô shouldô notô beô mistakenô forô ease.ô Engineô shortages,ô particularlyô linkedô toô Prattô &ô Whitneyãsô gearedô turbofanô issues,ô continueô toô disruptô deliveryô schedules.ô Cabinô interiors,ô avionics,ô andô fuselageô qualityô problemsô haveô addedô frictionô atô preciselyô theô momentô whenô airlinesô areô desperateô forô capacity.

Thatô tensionô explainsô whyô Airbusô cutô itsô deliveryô targetô lateô inô theô yearô whileô reaffirmingô itsô financialô guidance.ô Cashô generationô remainsô solid,ô butô theô pathwayô toô higherô outputô isô neitherô linearô norô guaranteed.ô Airbusãô backlogô hasô climbedô toô aô recordô 8,754ô aircraft,ô includingô aô widebodyô backlogô ofô moreô thanô 1,100.ô Theô challengeô isô notô demand.ô Itô isô execution.

Thisô isô whereô theô currentô cycleô becomesô interesting.ô Deliveriesô matterô becauseô theyô generateô cashô andô putô aircraftô intoô service.ô Ordersô matterô becauseô theyô signalô long-termô confidenceô andô shapeô theô competitiveô landscapeô forô decades.ô Airbusô isô winningô todayãsô operationalô contest.ô Boeingô isô rebuildingô tomorrows.

Investorsô haveô takenô notice.ô Boeingãsô shareô priceô roseô nearlyô 45%ô overô theô pastô yearô asô marketsô boughtô intoô theô narrativeô ofô aô slow,ô disciplinedô turnaroundô ratherô thanô aô dramaticô rebound.ô Airbusãô valuationô reflectsô steadierô performanceô butô alsoô theô realityô thatô itô isô alreadyô operatingô closerô toô itsô industrialô ceiling.

Theô widerô contextô mattersô too.ô Airlinesô areô orderingô withô aô differentô mindsetô thanô theyô didô fiveô orô tenô yearsô ago.ô Flexibility,ô fleetô commonality,ô andô long-termô supportô matterô asô muchô asô headlineô performanceô figures.ô Politicalô considerationsô haveô re-enteredô fleetô planningô inô aô wayô manyô believedô belongedô toô anô earlierô era.ô Manufacturersô areô noô longerô competingô solelyô onô productô andô price.ô Theyô areô navigatingô aô landscapeô whereô geopolitics,ô tradeô policy,ô andô industrialô sovereigntyô influenceô purchasingô decisions.

Competitionô betweenô Airbusô andô Boeingô hasô alwaysô beenô cyclical.ô Whatô feelsô differentô nowô isô theô asymmetry.ô Airbusô isô defendingô aô positionô ofô operationalô strengthô whileô managingô constraint.ô Boeingô isô climbingô backô fromô disruptionô withô theô helpô ofô politicalô tailwindsô andô renewedô customerô engagement.ô Bothô areô credible.ô Neitherô isô comfortable.

Lookingô ahead,ô theô balanceô betweenô deliveriesô andô ordersô willô remainô uneven.ô Airbusô willô continueô toô handô overô moreô aircraftô inô theô nearô term.ô Boeingô willô continueô toô rebuildô itsô backlogô andô productionô credibilityô stepô byô step.ô Theô questionô isô notô whichô manufacturerô ãwonãô 2025.ô Itô isô whetherô Boeingô canô translateô orderô momentumô intoô sustainedô industrialô performance,ô andô whetherô Airbusô canô liftô outputô withoutô compromisingô qualityô inô aô systemô alreadyô underô strain.

Theô authorô isô anô aviationô analyst.ô Xô handle:ô @AlexInAir.

ô