A shortage of experienced nature and conservation staff in Britain could threaten the country’s efforts to accelerate nature restoration and play its part in meeting global climate and biodiversity targets, according to sector insiders.

Workers from government, charities and businesses told the Thomson Reuters Foundation there are crucial gaps in the labour force, with intense competition for specialists such as ecologists and hydrologists.

“The productivity of the organisation is compromised because we can’t recruit or retain the sort of people that are needed,” said an industrial regulator at the government’s Environment Agency, speaking anonymously because of the sensitivity of the issue.

An August survey of more than 500 Prospect union members working in the sector, including in the Environment Agency, found that more than half identified a reduction in expert staff as one of the largest barriers to doing their work effectively.

Sally Hayns, CEO of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM), said a drop-off in conservation projects — often connected with infrastructure development — following the 2008 financial crash has contributed to the shortage of staff.

“Nowadays, there aren’t enough ecologists with sort of 10 years’ experience, and so they are like gold dust,” she said.

Meanwhile, she said, agencies and charities struggle to compete with the wages offered by private-sector organisations, which means they are losing people, including those in senior roles with specialist expertise.

A spokesperson for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) said the government “is going further and faster for nature than any other” and has boosted funding for the Environment Agency and Natural England, its advisory body on conservation.

Natural England’s chief officer of business management Kirsty Carter-Brown said the organisation’s headcount has grown by 40% over the past two years and it has a relatively low annual turnover of 9%. The organisation is directing more money towards staff well-being, she added.

The government published an updated Environmental Improvement Plan setting out a series of bold targets at the start of 2023, including proposals to protect 30% of land and seas and raise £1bn ($1.24bn) of private finance for nature per year by 2030.

That came after countries met at United Nations COP15 talks last December in Montreal to agree a global deal to protect and restore nature, as the loss of crucial biodiversity continues due to factors like deforestation, wetland drainage and pollution.

Many in the sector are concerned that staffing could prove a roadblock in Britain. Insiders cite shortages in the number of consultants with experience managing conservation projects, ecologists to advise local governments, or experts to monitor water quality.

This is all the more critical as Britain is set to roll out major policies like the Biodiversity Net Gain requirements for real estate in England — where new developments will need to ensure they have a net-positive impact on habitats. This will require local government to have greater access to expertise.

According to job site Conservation Careers, which posts more than 15,000 jobs worldwide each year, specialist positions like senior ecological consultants are becoming harder to fill — even for big, well-known conservation organisations.

“It’s a massive delivery risk for the Environmental Improvement Plan,” said Richard Benwell, chief executive of the charity Wildlife and Countryside Link.

“There are shortages of skills and labour across the environment sector, not just in those government agencies,” he said.

Insiders in government agencies said low pay, a cost-of-living crisis and internal job moves were responsible for a lack of experience and expertise — with some staff moving to private companies or leaving the sector for higher wages.

The Prospect Survey of major government agencies and charities found that about 38% of respondents earned £30,000 or less, despite being highly skilled, and 35% between £30,000 and £40,000. It also said low pay “disproportionately affected” women.

Earlier this year, Environment Agency CEO James Bevan told a parliamentary committee that some staff were using food parcels, and others were being forced to leave for financial reasons.

Bevan said his organisation had been able to recruit more than 1,000 staff in the last year, but they tended to be younger people or workers from different industries who required training and would take time to deliver results.

A civil servant working on policy in Defra said another problem is that gaining a promotion is not straightforward, so workers are incentivised to move across departments, leading to a high turnover within government and fewer chances to specialise.

“It takes longer to do things, there’s less institutional memory, you’re working with constantly changing teams and very variable levels of experience and expertise,” he said.

“You end up having the same conversations again.”

Although many nature and conservation projects are implemented by non-governmental organisations — who hire the most people in this area — and the private sector, government is crucial in areas like policy-setting and project approval.

“We do entirely rely on the machinery of government working for us to be able to deliver things,” said Mike Blackmore, director of operations at Wessex Rivers Trust, an environmental charity.

He said a lack of specialist knowledge and experience at government agencies often causes delays in permitting, which can jeopardise projects like river ecosystem restoration that can only be done in a specific time window.

Blackmore added that the 2008 crash and subsequent government austerity meant experienced people in government roles retired and were not replaced.

The education system may also be contributing to the lack of experienced staff coming through the pipeline.

Hayns from CIEEM said tight university budgets have made it harder to teach hands-on field work, which is time-consuming and expensive, meaning that many graduates are expected to get voluntary work experience to fill the gaps.

“They’re coming out of university not necessarily with the right practical skills that employers are looking for,” she said.

Hayns warned universities are being judged on how many graduates get into related, skilled employment, which means ecology-related courses are at risk.

She said her organisation is looking to help universities provide short courses, and exploring how to create vocational routes into the sector, making it easier for people with transferable skills like project and financial management.

A paper published last year in the Ecology and Evolution journal found that students are being given far less education on plant science compared to animals.

Sebastian Stroud, a postgraduate researcher at the University of Leeds and the paper’s lead author, said more needs to be done to integrate plant teaching across the education system, as well as providing tangible experiences with nature.

“If we want to protect natural environments, people need to be exposed to them,” he said. — Thomson Reuters Foundation

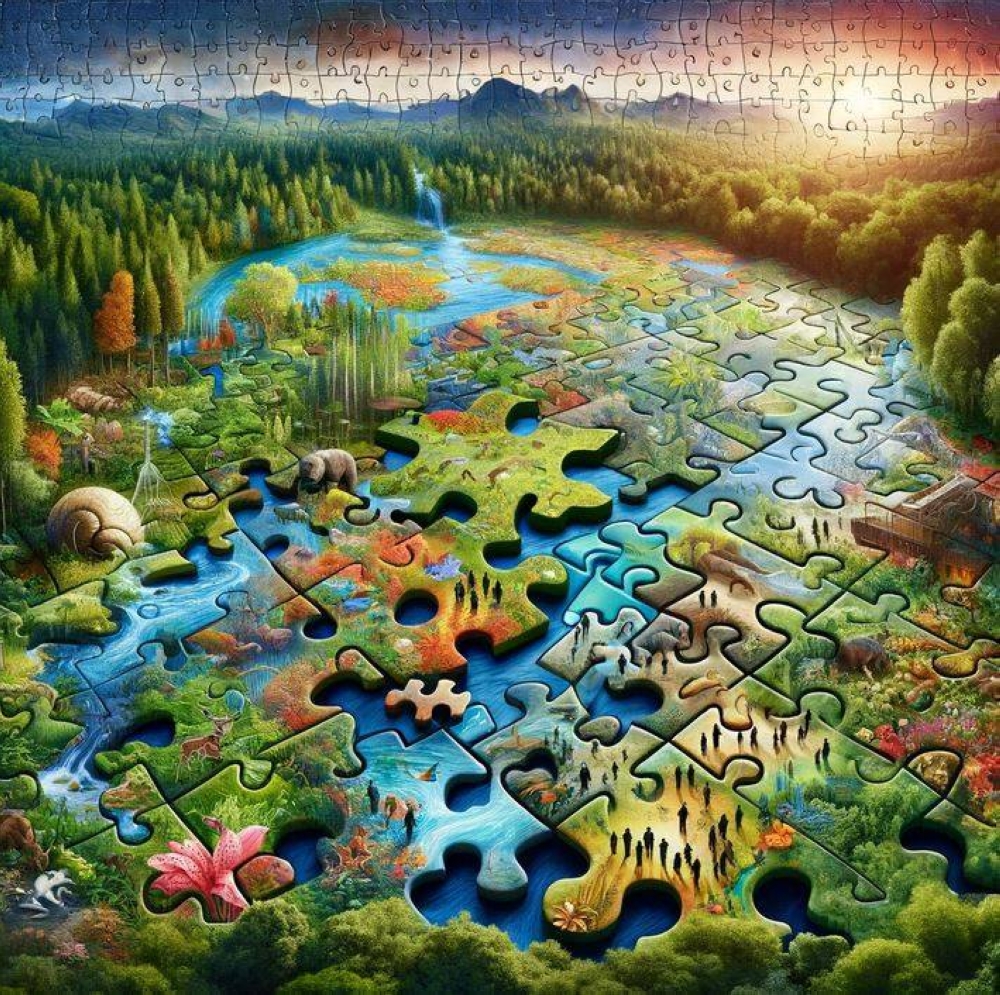

An illustration showing a puzzle of a thriving ecosystem, with missing pieces representing ecologists and hydrologists.