Last year zinc was the star performer among the major base metals traded on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

Might it be sister metal lead’s turn to shine this year?

The unglamorous heavy metal has already had a tumultuous start to 2017. LME three-month metal, currently trading around $2,340 per tonne, has notched up a year-to-date gain of over 16%, beating zinc into second place.

Funds have been quietly lifting their exposure. As of the close of last week the money manager net long position was equal to 18.5% of open interest, a record level since the LME started publishing such data in July 2014.

A ferocious squeeze on the London market has helped.

The LME’s benchmark cash-to-three-months spread traded out to $45.50 per tonne backwardation at one stage last month, a degree of tightness not seen since 2011.

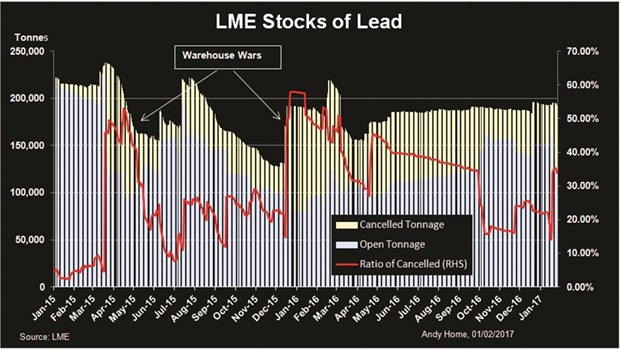

In the mix has been a dominant long position holder and a sharp rise in cancellations of LME lead stocks.

The amount of metal earmarked for physical load-out from the LME warehouse system currently stands at 67,225 tonnes, representing almost 36% of total exchange stocks.

Seasoned watchers of the London lead market might be forgiven for rolling their eyes at this point.

We’ve been here before.

There were similar squeezes on LME stocks in both March and December 2015 and neither of them had anything to do with real-world demand.

Rather, they resulted from “warehouse wars” as storage operators competed for stocks and rental revenues.

But this time might just be different because there is a growing sense that this opaque market might really be tightening up to the point that metal is now being hoarded in expectation of a physical squeeze later this year. Last month’s sharp contraction in time-spreads bore all the hallmarks of one of those periodic tussles for LME-stored lead that has enlivened an otherwise dull market in recent years. Some 15,000 tonnes of metal that were earmarked for physical load-out in the Dutch port of Vlissingen were placed back onto LME warrant.

Within days another 43,000 tonnes of LME stocks had been cancelled, primarily at the South Korean port of Busan but also across a range of European locations.

At the heart of all this stocks mayhem has been the unidentified entity gripping the nearby spreads.

At times it has controlled positions equivalent to between 80-90% of available LME tonnage. The latest exchange report shows it still there with 50-80% of stocks. Superficially, this might look like the latest round in the tit-for-tat smash-and-grab “warehouse wars” that caused similar spread and stocks disruption in both 2015 and early 2016.

LME metal would be cancelled and disappear from one location only to reappear in another, only for the original victim to turn aggressor and start the cycle again.

The long-term impact on LME stocks has been negligible. They started this year at 191,650 tonnes, little changed from 221,975 tonnes at the start of 2015.

But the word in the tight-knit lead trading community is that this time is different with traders rather than storage operators taking strategic physical positions in expectation of a looming squeeze on availability in the real world rather than paper market. The squeeze has already started upstream at the mine concentrates stage of the supply chain.

Treatment charges (TCs), which is what smelters charge miners for transforming raw material into metal, are the best indicator of what is happening in the concentrates part of the supply chain.

And, according to research house Wood Mackenzie, spot TCs into China are currently below $20 per tonne, down from $80 just three months ago and the lowest level since at least the turn of the decade.

In this respect lead is playing catch-up with zinc. The two metals are commonly found in the same deposits with lead the “ugly sister” by-product to zinc.

The closure due to exhaustion of mines such as Century in Australia and Lisheen in Ireland may have grabbed the zinc headlines but both were also producers of lead.

*Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are his own.