By James Palmer/Reuters

I prefer to work alone because I’ve found from past experience it’s just easier.

Still, it was hard not to cross paths with other journalists in Syria in the late summer and fall of 2012, where you were free to roam without government restrictions.

I first saw James Foley - whom the Islamic State (IS) executed this month - at a demonstration in Aleppo, a rebel stronghold. He was standing perfectly straight and steadily holding his camera as he filmed a handful of men dancing while drums were pounded and scores of people sang.

He arrived at the ad hoc police station another day seeking an interview with one of the leaders there while I was shooting photos. We shook hands and introduced ourselves then returned to our work. Apparently, neither of us could afford the time to chat.

When a firefight broke out late during another afternoon, Foley appeared nearby. After crossing the street, he waved a third journalist and me over to an apartment building where a number of rebels were climbing the stairs. I followed them to the roof. Foley was already in position and shooting in the doorway. He moved so I could pass and I extended the same professional courtesy by squatting down in an effort to stay out of his shot.

We departed that day without any ceremony, but the next morning I saw him sitting outside a shop sipping a soft drink. He smiled and waved to me. I guessed at the time he was pleased with the video he shot the previous afternoon and was looking forward to the day of work ahead.

We never ran into each other again.

Independent journalists reporting in war zones depend on their instincts and luck. Not simply to survive but to complete their work and earn a living.

When I arrived in Iraq in August 2005 news agencies were shutting down their bureaus and fleeing the country. The money for freelancers continuously flowed in. The work was so plentiful I sometimes had to turn down assignments.

In Syria, however, I gradually realised that even companies who usually used freelancers as a cheaper alternative to staff viewed me as a liability. They simply refused to embrace the risks involved - no editor wants the blood of a dead freelancer on his or her hands.

Even the highly competitive newspapers in London declined to touch me. One editor sent an e-mail advising me to leave Syria. He was further insuring himself against any harm I might encounter.

With no US or British troops on the ground in Syria to keep them absorbed, it was clear that news executives and readers in the West had far less interest in the country than in Iraq.

Despite the financial obstacles, I spent three weeks in Aleppo - Syria’s second largest city.

Abu Ali was among the first people to greet me there. He was a tall and gangly middle-aged tailor with a wife and three kids. Even with an automatic rifle slung over his shoulder, he never seemed threatening. When I told him I was from New York, he danced a jig on the sidewalk. Whenever I passed him after that he always offered me food and a drink.

Abu Ali helped set me up that night in an apartment where a group of Western-backed Free Syrian Army soldiers were camped. But throughout my stay in Aleppo, I rarely slept under the same roof on consecutive nights. I found this was a good way to move around and work.

Most of these places had been abandoned and were occupied by the rebels or activists. Some were still finely appointed - with ornate dining tables, chandeliers, thick drapes, china, glass vases and family photos - but topped with dust.

I spent several nights sleeping on the floor alongside a dozen other men in a former school for small children, which was converted into a police station. The walls were painted with pastels and decorated with flowers and animals.

One evening I crashed in a second-floor apartment across the street from an FSA post. I usually experienced no trouble falling asleep but the guttural moans of a man as he was beaten and whipped kept me awake that night.

Another night I slept in the examining chair of a dentist’s office. When I went back a few nights later, it was gone.

This arrangement was also beneficial because it was free. And that was characteristic of my time in Syria - other than what small snacks and drinks I purchased in the shops, I was never required to pay for anything.

I tried to buy a SIM card for my cell phone, but an activist brought me to a mobile phone shop and arranged the installation of one at no cost. When I asked him why it was free, he told me the card was taken from the dead body of a government soldier. I suppose it was equally possible that it was found on the corpse of a rebel, but I thought it was in poor taste to say that out loud.

If you report any conflict for more than a few weeks, the numbers of people you meet who are later killed add up quickly. But only a few of those stick with you for good.

For me, in Iraq, it was an infant with a congenital heart defect - her small chest expanded upward as she struggled for every breath while her eyes bulged seemingly begging for relief. She died less than a week after I met her.

And in Syria, it was Abu Ali.

A boisterous crowd of men chanted in unison as his body was carried aloft through a narrow alleyway. I photographed an image of the scene from a doorway without knowing it was him. But I soon recognised who it was after joining the crowd.

Abu Ali was laid on the floor of a mosque. A white sheet covering his body was pulled back to reveal only his face. The blood stains showed where three sniper bullets entered his abdomen.

Abu Ali’s brother made it clear to me that photos were prohibited. I set my cameras down on the ground at my feet before I stood over the body.

A fight nearly broke out while transporting the dead man to a cemetery nearby. One of the activists took issue with the photo ban and ignited a shouting match. He eventually relented but protested again as the body was lowered into its grave.

I walked away at that point. There was no reason to linger.

As I left the cemetery, a teenage boy pointed me toward the corpse of an alleged government spy lying prostrate in a crater where a shell landed. The right eye of the corpse was gouged out, perhaps as a threat to anyone else who was considering passing along information to the other side.

I recorded the scene with my camera and moved on.

There was always work in Syria for a freelance journalist, if you wanted it.

-James Palmer is a former independent reporter and photographer.

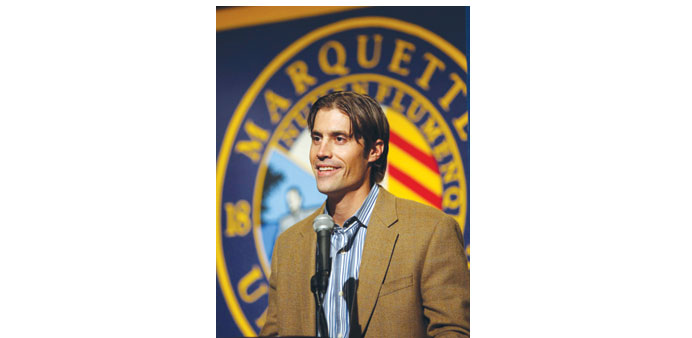

James Foley: murdered by militants