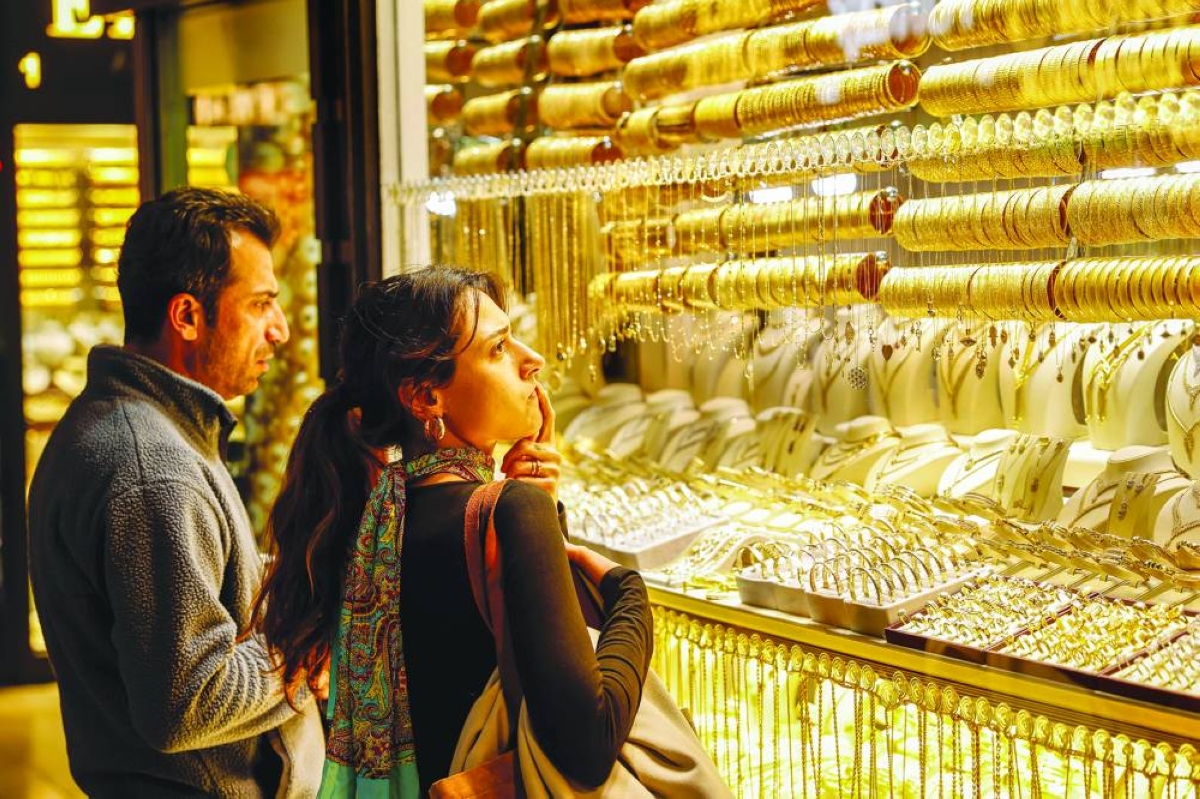

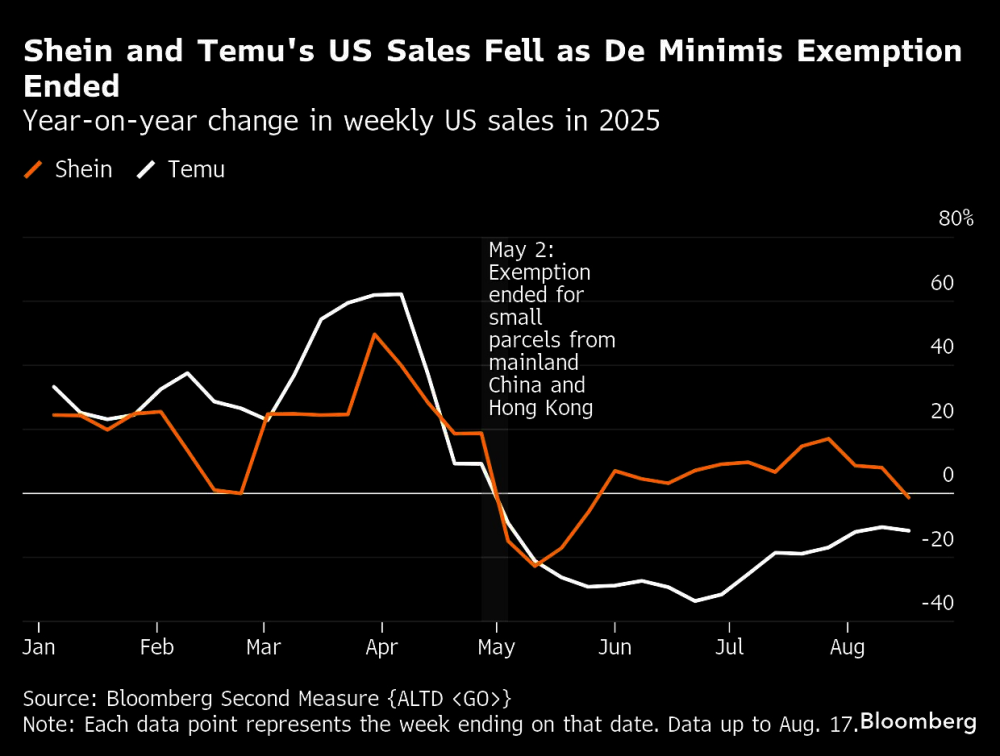

A Latin term that used to be little-known outside the world of customs brokers has become the stuff of headlines this year. That’s thanks to a decision by US President Donald Trump to end the tariff-free treatment of “de minimis” merchandise that had been in place for almost 90 years.The phrase — which loosely translates as “too small to matter” — refers to small packages shipped directly to consumers from abroad, millions of which arrive in the US every day. Qualifying as de minimis came with a huge perk: no customs declarations and no duties.This worked to the advantage of Chinese dis-count marketplaces such as Shein Group Ltd and Temu, which have tapped Americans’ appetite for buying cheap clothing, toys, electronics, and more, online. But the tariff exemption came to an end for packages from mainland China and Hong Kong on May 2, and ceased for the rest of the world on August 29.US consumers now face the prospect of higher prices and a longer wait for their orders. Ahead of the de minimis changes taking effect in August, many postal operators paused US-bound parcel shipments, citing a lack of clarity over how the tariffs will be collected.What was the US de minimis exemption?For a package to qualify, it had to have a re-tail value of no more than $800, which was high compared with other countries. The threshold in Canada is C$150 ($109) for parcels from the US and Mexico to be exempt from customs duties and C$20 ($15) for those from elsewhere, while in the European Union it’s €150 ($175). China, for its part, generally waives duties on packages worth up to about $7.The exemption in the US dated back to 1938, when Congress tweaked tariff rules to drop duties on low-cost items to avoid unnecessary expense for little reward, or, as one former Treasury official put it, “spending a dollar to collect 50 cents.” The exemption started at $1, where it stayed for decades before rising to $5 in 1990, $200 in 1993 and then jumping to $800 in 2016 during the Barack Obama presidency.What do the new rules mean for US consumers?The end of the de minimis exemption doesn’t mean Americans can’t order small packages from abroad. What’s changed is that the goods will be channelled through customs and incur levies.Sellers could absorb the additional costs or they could pass them on to consumers — either indirectly through a higher retail price, or directly by making buyers pay the duty.Shein and Temu raised prices on a wide range of products — from dresses to kitchenware — ahead of the tariffs kicking in on May 2. The average price of 98 products listed on Shein tracked by Bloomberg News increased by more than 20% by early May from two weeks prior.Elsewhere, South Korean beauty retailer Olive Young — which has been capitalising on the social media-fuelled popularity of Korean skincare products among American consumers — said it would add a 15% duty to all US orders at the checkout from August 27.The end of the de minimis carve-out could dis-proportionately impact lower-income households in America. Almost 75% of direct shipments imported by the poorest zip codes were de minimis, compared to 52% for the richest zip codes, according to analysis from the National Bureau of Economic Research using data from 2021.Could the end of the de minimis exemption cause supply chain disruption?Mail carriers in more than two dozen countries, including Australia, Singapore and Norway, temporarily suspended shipments to the US ahead of the August 29 de minimis cutoff date, as they grappled with how the new system will be implemented.The restrictions imposed by Deutsche Post and DHL Parcel Germany — part of DHL Group, one of the world’s largest couriers — reflected uncertainty over “how and by whom customs duties will be collected in the future, what addition-al data will be required, and how the data transmission to the US Customs and Border Protection will be carried out,” according to a company statement.Postal services have never had to handle this amount of paperwork before. The packages that enter the US now have to have a customs declaration that details the contents of the parcel, the value, and the country of origin of the goods — not just where they’re shipped from, but where they were made.Beyond the near-term disruption from potential backlogs, many e-commerce deliveries are likely to become slower because the added costs will make air cargo — already an expensive way to move freight — a potentially unprofitable mode of transportation for low-cost goods.Rather than fly on a plane and take a couple of days to arrive, a package might instead take a three-week journey on a container ship from China to the US West Coast.Which companies will be most affected by the de minimis carve-out disappearing?Low-cost online retailers such as Temu, Shein and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd’s AliExpress used the de minimis exemption for years to expand in the US — a trend that was supercharged by the Covid-era boom in e-commerce.Cross-border online retail has been a lifesaver for many Chinese manufacturers running on wafer-thin profit margins as spending by domestic shoppers plunged during the pandemic and never really recovered.Shein pioneered the model of targeting cost-conscious Americans with $2 blouses and $10 shirts during the pandemic, and Temu jumped in around 2022 with its “Shop Like a Billionaire” catchphrase. TikTok Shop, the shopping platform of the popular video app, is a more recent entrant.The end of the de minimis exemption appears to have had a dampening effect on US demand. Shein’s weekly sales dropped by as much as 23% year-on-year in late June before staging a recovery, according to Bloomberg Second Measure, which analyses credit and debit card transactions in the US. Temu saw a deeper decline — its weekly sales slumped by more than a third year-on-year in June and had yet to rebound to the prior year’s levels by mid-August.It’s not just the bottom line of the Chinese marketplaces that will be impacted by the de minimis changes. The exposure to tariffs will also hit “dropshippers,” who use e-commerce platforms to fulfil orders and send goods directly to customers, as well as small US businesses that have been importing products in batches under the $800 threshold to avoid tariffs. Small international businesses selling into the US will be affected too, including those using marketplaces such as eBay Inc and Etsy Inc.There are fears that the end of the de minimis exemption in the US could spur a flood of cheap goods, particularly those from China, to be sent to other countries instead. Amid concerns about domestic producers being undercut, markets including the UK are reviewing their own duty-free treatment of low-value imports.How have Trump’s de minimis changes evolved?Within days of taking office, the Trump administration suspended the de minimis rule for mainland China and Hong Kong. However, it soon delayed the change while the US Postal Service wrestled with how to implement the policy.The suspension was effectively reimposed on May 2, hitting buyers of packages worth up to $800 arriving from mainland China and Hong Kong with either a levy equivalent to 120% of their value or a flat fee of $100.When the US and China later announced an agreement to lower triple-digit tariffs on each other’s imports, Trump signed an executive order cutting the de minimis duty to 54%, while maintaining the flat fee.Then, on July 30, Trump said the de minimis ex-emption would end for items sent from anywhere in the world, although gifts valued at less than $100 will remain duty-free. According to a White House fact sheet, starting August 29, a posted package will be taxed in one of two ways:* The importer can pay a percentage levy on the parcel’s value. This is equivalent to the pre-vailing tariff rate the US has assigned to goods from the country of origin as part of Trump’s broader trade war.* Or, for the first six months of the new policy, the importer can pay a flat duty ranging from $80 to $200 per item, depending on the applicable country-specific tariff rate.What effect has the US de minimis exemption had?With the threshold as high as it was in the US, around 4mn small packages claiming de minimis exemptions crossed into the US every day in 2024, according to US Customs and Border Protection. These parcels often went unchecked be-fore being transferred to a truck for delivery directly to the consumer’s doorstep.This helped Americans access lots of cheap merchandise sold by e-commerce retailers in China. It also strained global supply chains, raised air cargo costs and swamped border enforcement efforts.The packages are thought to be one of the ways illegal drugs such as fentanyl have been smug-gled into the US and how other goods have entered the country in violation of rules against imports from regions known for human-rights abuses.The administration of President Joe Biden was well on its way to cracking down on de minimis abuses before he lost his re-election bid in November 2024, so Trump’s decision to eliminate the exemption wasn’t a complete surprise.How much trade did the de minimis rule affect?The de minimis exemption affected quite a bit of trade in both volume and value, with both rising exponentially. Such packages used to be confined to t-shirts and small electronics, but they’ve expanded to include bigger-ticket items such as electric bikes retailing for $799.According to a White House fact sheet, the number of individual shipments to the US claiming de minimis exemptions surged to nearly 1.4bn in 2024, up from 134mn a decade earlier. While China officially reported about $23bn worth of small parcel exports to the US last year, Nomura Holdings Inc estimates as much as $46bn of US-bound packages came from the country. (There’s a discrepancy because with so many parcels, it’s hard to count all of them in official statistics.) That’s still just a small fraction of the value of total US goods imports, which last year surpassed $3.2tn. Consequently, the suspension of the de minimis ex-emption isn’t expected to have a major effect on the US economy.