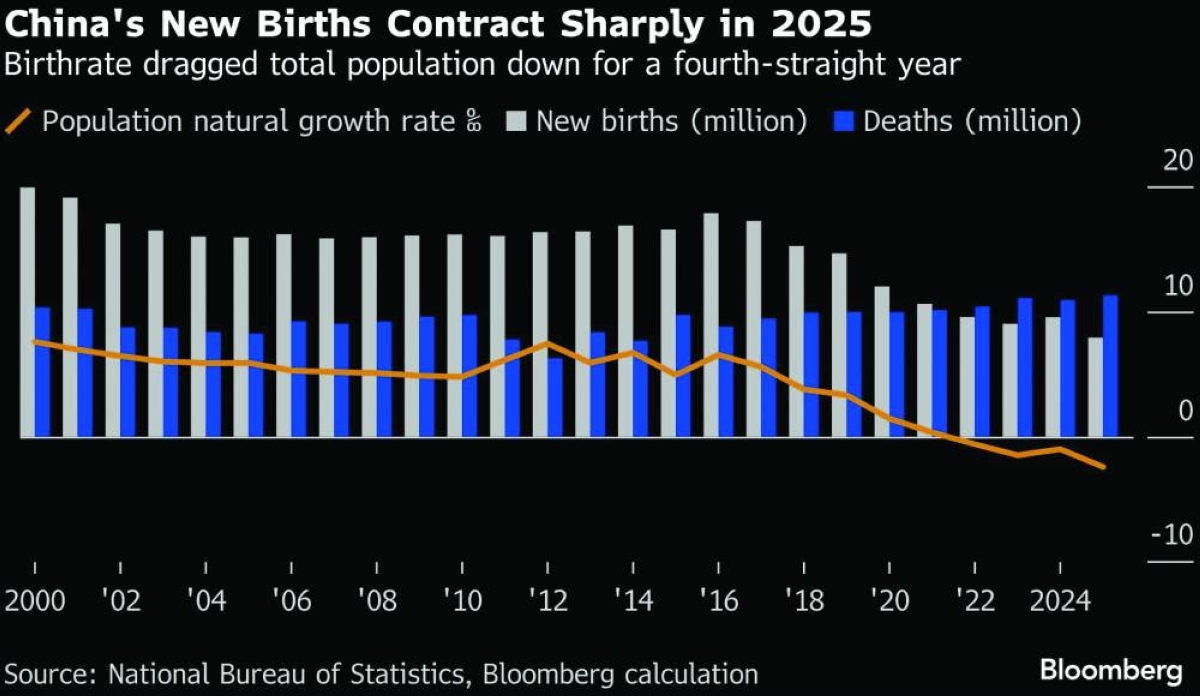

China’s population is shrinking at a pace not seen in decades — a stark reversal for a country long defined by its sheer demographic scale.After losing its crown as the world’s most populous nation to India in 2023, official figures show that in 2025 China recorded its steepest annual drop in population since the Great Famine of 1960 under Mao Zedong, as falling birthrates and an ageing society converge — despite the end of its one-child policy.The shift raises pressing questions about how much scope Beijing has to alter the trajectory that has far-reaching economic consequences. What’s happening to China’s population?A drop in the number of births and an increase in deaths left mainland China with 3.39mn fewer people in 2025 than a year earlier, according to data from the National Statistics Bureau.China recorded 7.93mn births in 2025, the lowest level since at least the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Births have fallen every year since 2016, aside from a brief uptick in 2024.Despite the end to China’s one-child policy a decade ago, a longstanding preference for sons led some Chinese families to abort female fetuses, skewing the sex ratio at birth in earlier decades. Although that ratio has stabilised at around 104 boys per 100 girls in recent years, there is still a shortage of women of child-bearing age today.China’s fertility rate, or the average number of lifetime births per woman, fell to 1.3 in 2020, far below the 2.1 needed to keep the population stable, excluding migration. Outward migration by Chinese citizens appears to have increased in recent years, further weighing on population growth.The country’s demographic problem is also visible in the workforce. The working-age population — those aged between 16 to 59 — has been contracting for years and in 2025 fell to about 60.6% of the total population, down from more than 70% a decade earlier. Projections suggest that 30% of the population will be 60 or older by 2034. What’s the impact?A shrinking population could erode China’s long-term growth potential and diminish the likelihood that its economy will overtake the US in size — especially as the US population is expected to continue growing.If China’s overall population — and working-age cohort — keeps declining, fewer people are likely to be employed, which could push up labour costs and raise the price of manufactured goods.Raising the retirement age could ease some of that pressure. For more than four decades, China kept the retirement age at 60 for men and 55 for female white-collar workers, even as life-expectancy rose. In 2024, Beijing adopted a plan to gradually delay retirement by as much as five years over a 15-year period — a move that promptly triggered public discontent.Fewer people starting families would also weigh on long-term housing demand, with potential knock-on effects for construction activity and China’s iron ore industry. At the same time, a shrinking workforce would make it harder for the government to finance its underfunded national pension system, as fewer workers pay into the system while the number of retirees continues to rise.There could also be ripple effects beyond China. A smaller cohort of young people would likely reduce the number of Chinese students studying in the US, Australia and other countries, with implications for universities and local economies that depend on them. What’s being done about the birthrate?In 2016, China’s top decision-making body, the Communist Party’s Politburo, ended the one-child policy to allow couples to have two children. In 2021, the rules were revised again to permit up to three children.The 2016 rule that allowed couples to have two kids worked at first: The number of newborns that year rose to 17.9mn, more than 1mn higher than in 2015. But births have fallen each year after that, except for in 2024.China began rolling out childcare subsidies last year. Couples are offered about $500 a year for each child born on or after January 1, 2025, until they reach the age of three. Some regions have also extended parental leave and offered tax rebates for parents, though such incentives are widely seen as too modest to meaningfully boost birthrates. Where did the one-child policy come from?After the creation of the People’s Republic and the end of the civil war, the government trained tens of thousands of “barefoot doctors” to bring healthcare to poor and rural areas. The mortality rate plummeted and the population growth rate rose from 16 per thousand in 1949 to 25 per thousand just five years later.This prompted the first attempts to encourage family planning in 1953. Even so, China’s population expanded to more than 800mn in the late 1960s. By the 1970s, China was grappling with food and housing shortages. In 1979, leader Deng Xiaoping decided to limit most couples to a single child, with exceptions for rural farmers, ethnic minorities and certain circumstances, such as when a first child was disabled.Enforcement was often coercive. According to Human Rights Watch, women were forced to have abortions. Children born outside the state plan were denied a hukou — a government registration required to access public services and other benefits. How else is China trying to fix the problem?Beijing it trying to lower the financial and time costs of raising children, as many couples say they can only afford to have one child — if any. The government has taken steps to shut down the for-profit, after-school tutoring industry to rein in education costs and has issued guidelines aimed at reducing abortions while providing more support for women raising children.Still, if the experience of developed nations such as Japan or South Korea is any guide, it’s extremely difficult — if not impossible — to radically raise birthrates, even with subsidies, free childcare and generous parental leave.

Saturday, February 14, 2026

|

Daily Newspaper published by GPPC Doha, Qatar.