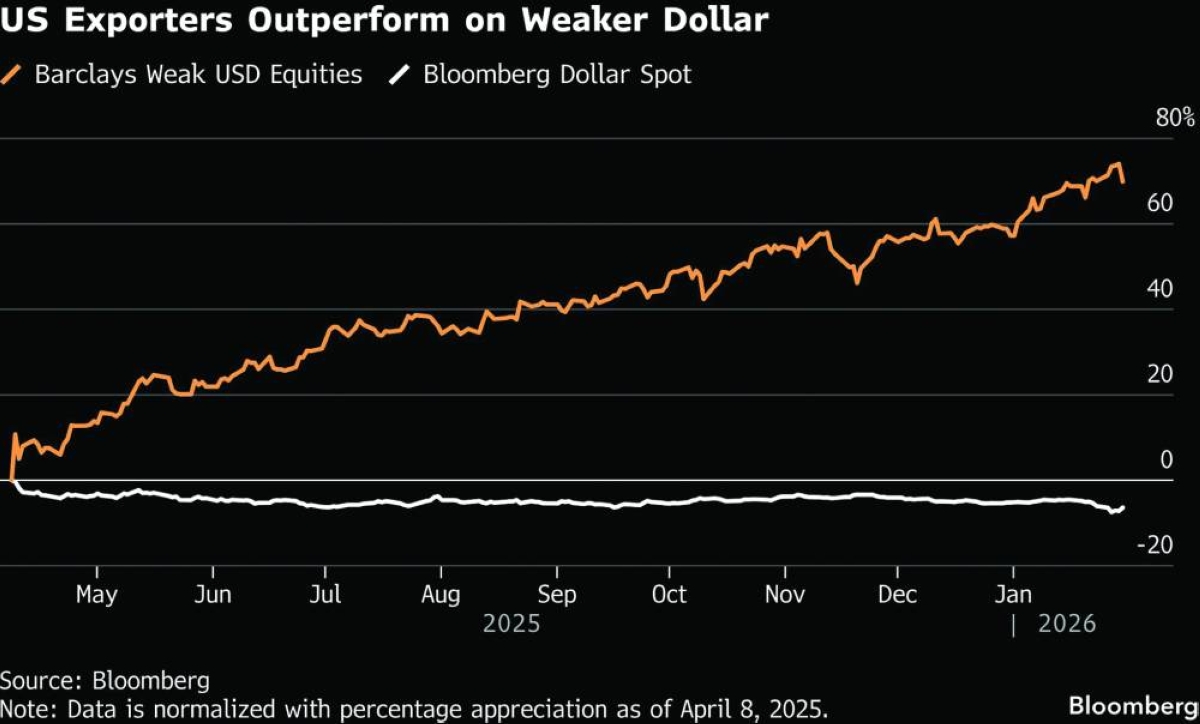

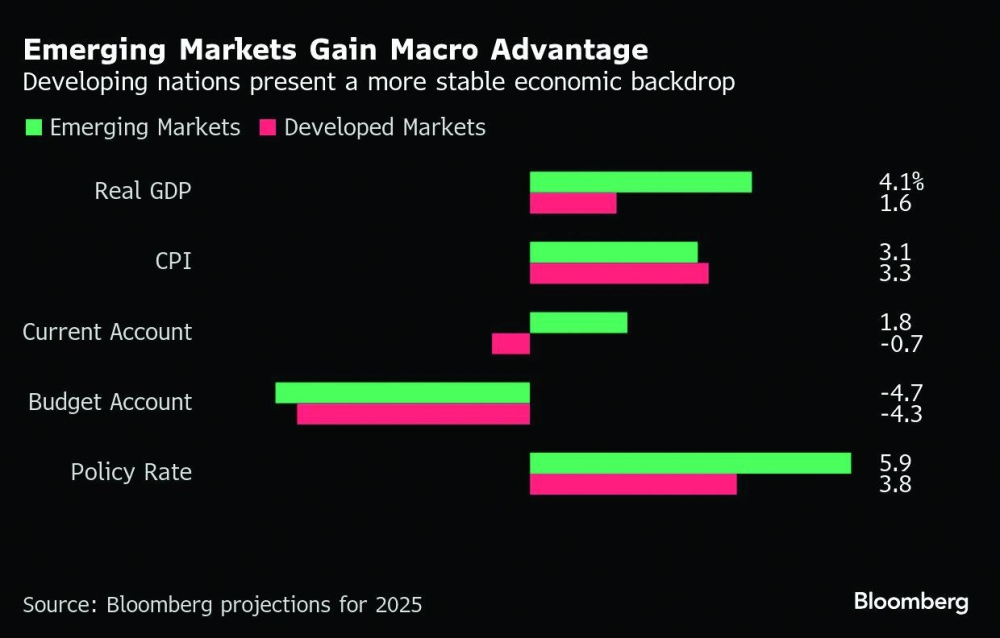

To President Donald Trump, the dollar is like a yo-yo that he can make go up and down. To equity investors, the toy looks broken — and a weaker dollar is now the latest obstacle they have to contend with when valuing stocks.The calculus is not easy, since a slumping dollar is hardly straight poison for the US stock market. Exporters will more readily find buyers, multinational companies will benefit from stronger overseas revenues.But it has drawbacks. American assets become less attractive, slowing the flow of funds into US companies and driving money to international markets. US manufacturers have to pay more for input materials produced abroad, potentially importing inflation for end products sold at home.The president insists he’s not worried about the dollar, no matter its latest slide — a comment that spooked forex traders and, eventually, led Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to reiterate the long-standing policy that Washington favours a strong currency. The greenback jumped Friday by the most since May, but still, it remains sharply lower than a year ago, and that has implications for equity traders.“Having a weakening dollar is a net negative for the US stock market,” said Chris Zaccarelli, chief investment officer at Northlight Asset Management.He expects investors to reorient their portfolios to overweight export-oriented US stocks. And why not? Since the market bottomed on April 8, a Barclays Plc basket of companies that benefit from a weak dollar has soared 70% compared with 39% for the S&P 500. A basket of firms that benefit from a strong currency is up just 11%.The weak-dollar group includes Lam Research Corp, Freeport-McMoRan Inc and News Corp, all companies that get the bulk of revenues abroad. It’s up 8.1% just this month, as Bloomberg’s dollar index slid 1.3%. That bodes poorly for stocks like Dollar General Corp, Nucor Corp and Union Pacific Corp, which are among those that benefit from a strong greenback.The weak dollar is also sparking a rotation from US stocks into international equities, where returns in local currencies have starkly beaten American indexes.The S&P 500’s 1.4% gain in 2026 is not far behind the Stoxx Europe 600’s 3.2% gain. Factor in the dollar’s drop, though, and the US index is a bigger laggard. Europe’s benchmark is up 4.4%, stocks are 7.2% in Japan and an eye-popping 17% in Brazil.“There’s a lot of people both domestically in the US as well as internationally thinking about opportunities outside of the US because you’ll get the opportunity of a lower valuation and potentially the tailwind of currency on your side,” Zaccarelli said.The same dynamic played out last year, when many of those markets outperformed the S&P 500 in local currencies – and absolutely clobbered it when adjusted for the dollar.The relative performance can have a self-perpetuating effect. As overseas investors see their US holdings lose value in local currency terms, they become more inclined to pull money from American companies.“You want to own strengthening currencies,” said Michael Rosen, president and chief investment officer at Angeles Investment Advisors, which oversees nearly $47bn in assets.Dollar weakness is not all gravy for foreign markets, particularly for export-oriented economies like those in Taiwan and South Korea and Europe. Some of their biggest companies, like Samsung or Taiwan Semiconductor, may see margins crimped as local-currency revenues decline.Still, a softer greenback can act as a powerful macroeconomic tailwind as cheaper dollar funding eases global and local financial conditions, reducing the cost of capital for firms across the region. Key imports priced in dollars — from energy to raw materials — become cheaper, allowing companies to maintain or improve margins.“South Korea and Taiwan have traditionally been winners from dollar weakness,” said Gary Dugan, chief executive officer at Global CIO Office. “Singapore could benefit from capital flows as global investors seek strong currencies with yielding assets such as REITs.”Companies in the Stoxx 600 generate nearly 60% of their sales overseas, with many active in the US market, according to data from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. That compares with 15% to 28% for companies in the US, China and broader emerging market indexes.As a consequence, investors in European stocks have been picking companies that stay closer to home.“My strategy is to look at companies that produce locally and are not obliged to convert and repatriate earnings back,” said Gilles Guibout, portfolio manager at BNP Paribas AM. “Obviously, it’s also a strategy to favor domestic stocks that are little concerned by the fluctuation of the dollar.”An analysis by Citigroup strategists shows that a 10% rise in the euro versus the dollar could reduce European earnings per share by about 2%. Companies in the commodities, food and beverage, health-care, luxury goods and auto sectors are among the most exposed, they found.Importantly, a weak dollar is not determinative for stock prices or corporate earnings in the US. In the past 25 years, changes in the greenback and rolling annual per-share earnings growth in US stocks have had a correlation of just 0.04 on a quarterly basis, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.“Only sharp surges or selloffs in the dollar have historically mattered for index earnings,” BI analyst Nathaniel Welnhofer wrote.Arguably, stock investors are in a period of a sharp selloff — though the dollar advanced Friday after Trump nominated Kevin Warsh to lead the Federal Reserve. Bannockburn Capital Markets expects an 8% to 9% decline this year.A dollar rout of that magnitude is something traders haven’t had to grapple with in earnest for years. Washington’s official position since at least the 1980s has been that a strong currency is in the best interests of the US. Bessent reiterated that last week.Still, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index has stumbled almost 10% since Trump’s inauguration, with currency traders souring on the greenback because of the administration’s actions. Trump has renewed tariff threats, ramped up pressure on the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates and war-mongered to seek dominance of the Western hemisphere.“This is an administration that clearly wants a weaker dollar and the markets are going to give it to him,” Rosen said.

Wednesday, February 11, 2026

|

Daily Newspaper published by GPPC Doha, Qatar.