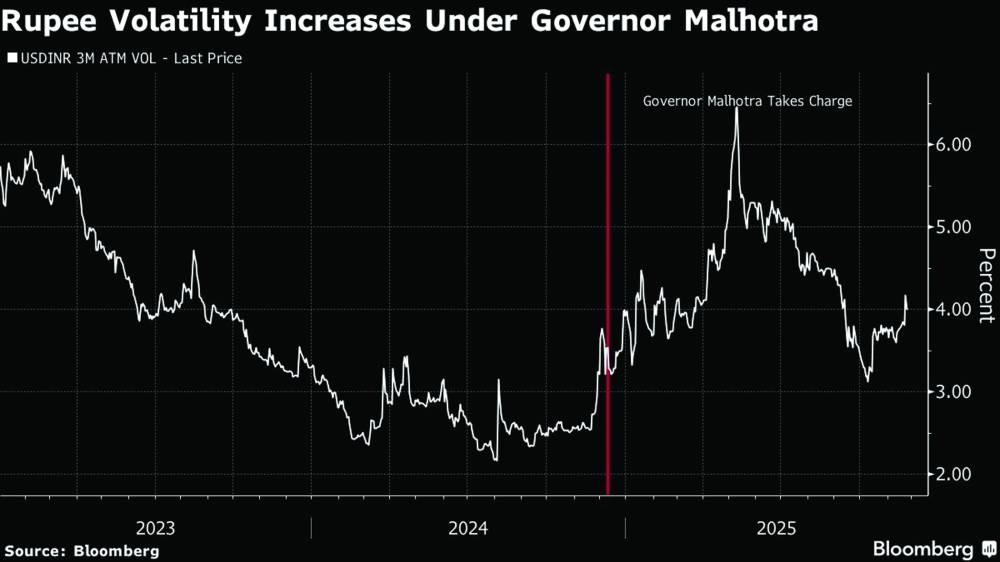

The US-India trade deal has blown away clouds over the unloved Indian rupee and is probably enough to pause relentless foreign selling in stocks, but investors say earnings growth must rebound and fundamentals improve for sustained buying. The long-awaited deal sparked a surge in the stock market and the rupee’s best rally in seven years on Tuesday, as it signalled improving diplomatic and trade relations with the USThat, however, was just one of the factors hanging over the currency and stock markets which have underperformed regional and global peers by a wide margin since the beginning of last year and seen foreign allocations dwindle to a two-decade low. Although near record peaks, Indian equities are vulnerable to disruption from artificial intelligence and, without any companies in the sector, have been left behind in the rush to AI.Details of the trade deal also remain sparse, even if they do allow companies to at least start planning capital spending. “I’m not convinced tariffs have an immediate impact, but it certainly feeds into sentiment — that’s probably the best way to think of it,” said Michael Bourke, head of global emerging markets for equities at M&G Investments. “Just because tariffs have gone down, do you suddenly see earnings surge? (I’m) not yet convinced that’s a line I would draw,” he said. The deal is meaningful for markets, but primarily for sentiment and valuation rather than near-term earnings uplift, said Naomi Waistell, fund manager in the emerging equities team at Carmignac, which manages $48.5bn in assets. “The deal does not resolve some of the recent issues surrounding Indian equities: still-elevated valuations... relatively lower forward earnings growth versus EM peers and a lack of globally scalable AI-beneficiary businesses.” Foreign investors have pulled roughly $23bn out of Indian stocks since the start of 2025, although they poured in $580mn on Tuesday. Vikas Jain, head of India fixed income, currencies and commodities trading at Bank of America in Mumbai, said there should be some revival in the near-term for foreign investor flows. “The underweight investors will come to immediate neutral position. Going overweight will depend on growth revival and the kind of policies that are announced by the government.” Analysts and traders say that the deal should also offer respite to India’s battered currency. The rupee has been the worst performing Asian currency in the past 12 months, requiring the central bank to consistently come to its defence as it slid from near 88 per dollar when the tariffs were imposed to a record low of almost 92 in January. Heightened appetite among firms to hedge against the rupee weakness and the central bank’s inclination to bolster FX reserves are among the factors traders say could stand in the way of an extended rally in the currency. “Tariffs on Indian goods had created a balance-of-payments risk for India, contributing to INR depreciation. The trade deal breaks this loop... encouraging foreign investors to evaluate Indian equities more objectively,” said California-based Peeyush Mittal, portfolio manager at Matthews Asia. India’s benchmark index has risen a respectable 10% in the past 12 months but pales in comparison to South Korea’s Kospi’s 118% surge and Taiwan stocks’ 42% gain in the same period. The risks from lacking obvious AI winners was at play on Wednesday as well with Indian IT firms’ stocks down over 6% after AI firm Anthropic launched workplace productivity tools, raising concerns of disruption across the sector. To be sure, some investors remain bullish on India and view it as a compelling trade. Sam Konrad, investment manager for Asian equities at Jupiter Asset Management, was slightly underweight India for most of 2025 but has been adding to his fund’s holdings over the past few weeks. M&G’s Bourke has also been a recent buyer of Indian financials, although remains underweight. Bigger allocations may take longer. Profit growth for Indian companies has remained in high single digits for six straight quarters, well below the 15%-25% growth recorded between 2020-21 and 2023-24.

Tuesday, February 17, 2026

|

Daily Newspaper published by GPPC Doha, Qatar.