Agencies/New Delhi

|

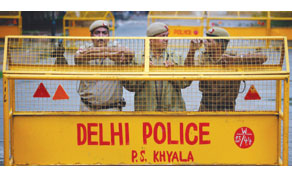

| Policemen stand guard behind a barricade at the site where veteran social activist Anna Hazare is scheduled to start his fast in New Delhi. Hazare renews a fast to the death in New Delhi today to force tougher laws against corruption, to the dismay of the embattled government as it grapples with scandals and a slowing economy |

Veteran anti-corruption campaigner Anna Hazare headed for a showdown with police yesterday when he vowed to court arrest after being banned from beginning a hunger strike in New Delhi.

Hazare had planned to begin a “fast unto death” today at a park to pressure the government to add more teeth to a new anti-corruption law that is under consideration in parliament.

“We have denied permission because the issue is that of timing,” police spokesman Rajan Bhagat said.

“The Central Public Works Department which owns the park has said the park was available for only three days and Mr Hazare must give an undertaking that his programme will not exceed that time-frame,” Bhagat said.

Police had also asked him to ensure that no more than 5,000 supporters would gather at the protest site.

Kiran Bedi, India’s first woman police officer, who speaks on behalf of the campaign, said Hazare and anti-graft supporters would defy the ban.

“We will court arrest tomorrow,” she said, meaning that the protesters will offer themselves to be taken into custody.

“These conditions are unconstitutional. You cannot limit our fast. You cannot limit our fundamental rights,” Bedi told reporters.

“You can do that only if our protest turns violent. If it is not so, then you cannot interfere,” the former police officer argued.

Hazare, a 74-year-old devotee of Mahatma Gandhi, staged a 98-hour hunger strike in April which led to the government allowing him and his supporters to help draft the new anti-corruption law, called the “Lokpal” bill.

The April protest caught the country’s attention and was widely supported by celebrities at a time when anger over corruption is high after a string of scandals affecting federal and state ministers.

The proposed new anti-corruption law will create a new ombudsman tasked with investigating and prosecuting politicians and bureaucrats, but Hazare wants the prime minister and higher judiciary to come under scrutiny.

Under the draft law, the premier and top judicial figures will be excluded from the purview of the ombudsman.

“Those who don’t agree with this bill can put forward their views to parliament, political parties and even the press,” Primei Minister Manmohan Singh said in his Independence Day speech yesterday.

“However, I also believe that they should not resort to hunger strikes and fasts unto death.”

During his April strike, Hazare called for corrupt ministers to be hanged, telling a cheering crowd that “sometimes you need to resort to violence.”

Hazare’s campaign, fanned by social networking sites and a raucous TV and print media, will be another headache for the ruling Congress Party when government resumes work today, the day after India celebrates the 64th year of independence from British rule.

“As soon as the government listens to the majority’s demand, we will stop our fast,” Suresh Pathare, Hazare’s personal assistant, said.

But this time around, Hazare’s fast may not have the same impact as his previous efforts. He has sparked a backlash of his own, with critics saying his methods are tantamount to blackmailing an elected government into changing policy.

“Manmohan Singh remains as weak as he has been,” said D H Pai Panandiker, head of New Delhi-based think tank RPG Foundation, but “the response to Anna Hazare may not be as strong as he anticipates.”

In a sign of how Hazare has made the government nervous, ruling party officials over the weekend launched aggressive attacks on the social activist, saying he too was involved in graft cases.

Congress spokesman Manish Tewari told local media that Hazare was surrounded by “armchair fascists, overground Maoists, closet anarchists... lurking behind forces of right reaction and funded by invisible donors whose links may go back a long way abroad.”

Those attacks may backfire among a public increasingly critical of the government.

Accused of being a “lame duck”, Singh has struggled to regain the policy initiative after scandals, including allegations of bribery and conspiracy in a $39bn telecoms scam that has sent two coalition politicians to trial.

Reforms such as making it easier to acquire land for industrial projects - the kind of investment India needs to sustain its 8% growth momentum - are slow to move.

Singh’s image took another beating after police, using batons and tear gas, broke up another fast led by yoga guru Baba Ramdev in June, prompting the Supreme Court to question the intervention.