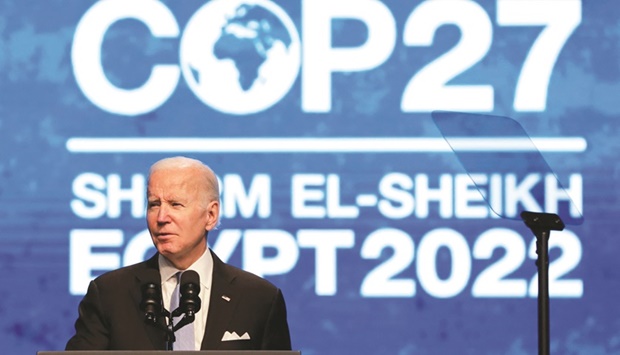

US President Joe Biden told the COP27 climate conference in Egypt yesterday that global warming posed an existential threat to the planet and promised the United States would meet its targets for fighting it.

His speech at the summit in the seaside resort town of Sharm el-Sheikh was intended pump up global ambition to prevent the worst of climate change, even as a slew of other crises – from a land war in Europe to rampant inflation – distract international focus.

A quartet of protesters briefly interrupted Biden’s speech by howling and trying to unfurl a banner before UN police removed them.

“Carbon offsetting is a false solution,” one of them – apparently an indigenous man from Latin or North America – shouted as he was escorted away from the venue.

He was referring to a US scheme whereby business can compensate for CO2 pollution by investing in developing world climate projects that reduce planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are headed toward impended climate collapse, and Jeff Bezos will not save us,” the man said.

The Energy Transition Accelerator carbon offset unveiled by US special climate envoy John Kerry this week in Sharm el-Sheikh is backed by the Rockefeller Fund and the Amazon founder through his Bezos Earth Fund.

The use of so-called voluntary carbon markets to drive down CO2 pollution remains highly controversial, with many analysts saying such difficult-to-monitor practices do not give business a strong enough incentive to reduce their own emissions.

During the 22-minute speech in COP27’s packed plenary hall, the climate activists howled like coyotes and were unfurling a banner when UN police stopped them.

It is not known whether the protesters were arrested, escorted out of the conference venue or simply released.

“The climate crisis is about human security, economic security, environmental security, national security, and the very life of the planet,” Biden told a crowded room of delegates at the UN summit.

“I can stand here as president of the United States of America and say with confidence, the United States of America will meet our emissions targets by 2030,” he said, outlining steps being taken by the world’s second-biggest greenhouse gas emitter.

Prior to his arrival, Biden’s administration unveiled a domestic plan to crack down on the US oil and gas industry’s emissions of methane, one of the most powerful greenhouse gases.

The move defied months of lobbying by drillers.

Washington and the EU also issued a joint declaration alongside Japan, Canada, Norway, Singapore and Britain pledging more action on oil industry methane.

That declaration was meant to build on an international deal launched last year and since signed by 119 nations to cut economy-wide emissions 30% this decade.

“Cutting methane by at least 30% by 2030 can be our best chance keep within reach 1.5° Celsius,” Biden said, referring to the central goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit the global temperature rise.

Biden said global crises, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, were not an excuse to lower climate ambition.

“Against this backdrop, it’s more urgent than ever that we double down on our climate commitments. Russia’s war only enhances the urgency of the need to transition the world off its dependence on fossil fuels,” he said.

The announcements come under a cloud of scepticism that world governments are doing enough to address the climate challenge.

A United Nations report released last week showed that global emissions are on track to rise 10.6% by 2030 from 2010 levels, even as devastating storms, droughts, wildfires and floods are already inflict billions of dollars in damage worldwide.

Scientists say emissions must instead drop 43% by that time to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial temperatures as targeted by the Paris Agreement of 2015.

Above that threshold, climate change risks start spinning out of control.

Many countries, including the US and members of the European Union, have also been calling for a near-term increase in the supply of fossil fuels to bring down consumer energy prices that spiked after Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine.

Washington has repeatedly said its calls to boost oil and gas production do not conflict with its longer-term ambition to decarbonise the US economy.

During his speech, Biden also promised an increase in funding to help other countries embrace the energy transition and adapt and prepare for the impacts of a warmer world.

That issue has been a sore point at the talks: wealthy nations have so far failed to fully deliver $100mn promised annually for climate adaptation.

Last year’s transfer came to only about $83bn.

“He announced a slew of new climate programmes, but he couldn’t deliver what the developing world most wants – enough money to adapt to climate extremes,” said Alice Hill of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group and a former Obama administration official.

She pointed out that Biden will need the US Congress to boost that funding, which could become more difficult after his Democratic party lost seats in this week’s midterm elections.

Harjeet Singh, head of policy and advocacy group Climate Action Network International, also criticised Biden for not providing clear support for a proposal to have wealthy nations pay for climate damage in poor countries.

“It’s radio silence on loss and damage finance,” Singh said, calling the US president “out of touch with the reality of the climate crisis”.

US President Joe Biden