Tens of millions of people across Pakistan were yesterday battling the worst monsoon floods in a decade, with countless homes washed away, vital farmland destroyed and the country’s main river threatening to burst its banks.

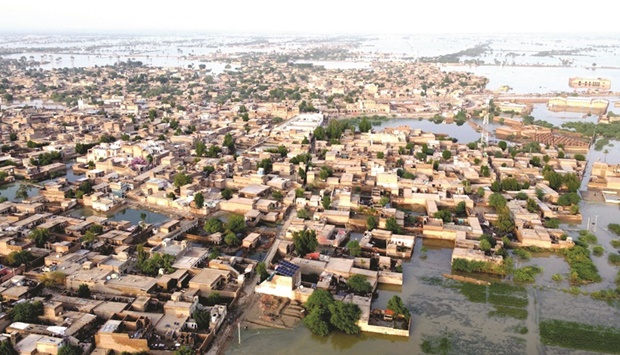

Climate Change Minister Sherry Rehman said a third of the nation was under water, creating a “crisis of unimaginable proportions”.

Officials say 1,136 people have died since June, when the seasonal rains began, but the final toll could be higher as hundreds of villages in the mountainous north have been cut off after flood-swollen rivers washed away roads and bridges.

“To see the devastation on the ground is really mind-boggling,” Rehman told AFP in an interview.

“When we send in water pumps, they say ‘Where do we pump the water?’ It’s all one big ocean, there’s no dry land to pump the water out.”

Rehman described the country being under water as akin to a dystopian movie.

She also expected the death toll to rise as many areas in the north of the country, where dozens of rivers are still in full flood, remain cut off.

Rehman renewed the government’s appeal for international assistance, while also blaming major industrialised countries for their role in global warming.

Pakistan is responsible for less than one percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, but is eighth on a list compiled by the NGO Germanwatch of countries deemed most vulnerable to extreme weather caused by climate change.

“It’s time for the big emitters to review their policies. We have crossed what is clearly a threshold,” she said.

“The multilateral forum pledges or ambitions voiced by other countries — the rich countries, that have gotten rich on the back of fossil fuels — they don’t really come through.”

Rehman said Pakistan’s economy, already in crisis, would be badly hit by the flooding.

“Sindh is half of Pakistan’s breadbasket and will not be able to grow anything at all next season,” she predicted.

“Not only will our exports be impacted, but our food security will take a hit.”

Rehman said a proper assessment of the damage caused by the flooding would take time.

“Right now, after everyone is actually rescued, we will be feeding and providing cooked meals and shelter,” she said.

“We need to also look for the spread of medical camps, because disease is always the next predator in such an environment.”

Early estimates put the damage from Pakistan’s deadly floods at more than $10bn, its planning minister said, adding that the world has an obligation to help the South Asian nation cope with the effects of man-made climate change.

“I think it is going to be huge. So far, (a) very early, preliminary estimate is that it is big, it is higher than $10bn,” Ahsan Iqbal told Reuters in an interview.

“So far we have lost more than 1,000 human lives. There is damage to almost nearly one million houses,” Iqbal said at his office.

“People have actually lost their complete livelihood.”

The minister said it might take five years to rebuild and rehabilitate the nation of 200mn people, while in the near term it will be confronted with acute food shortages.

The annual monsoon is essential for irrigating crops and replenishing lakes and dams across the Indian subcontinent, but it can also bring destruction.

This year’s flooding has affected more than 33mn people — one in seven Pakistanis — said the National Disaster Management Authority.

This year’s floods are comparable to those of 2010, the worst on record, when more than 2,000 people died.

Flood victims have taken refuge in makeshift camps that have sprung up across the country, where desperation is setting in.

“Living here is miserable. Our self-respect is at stake,” said Fazal e Malik, sheltering in the grounds of a school now home to around 2,500 people in the town of Nowshera in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

“I stink but there is no place to take a shower. There are no fans.”

Near Sukkur, a city in southern Sindh province and home to an ageing colonial-era barrage on the Indus River that is vital to preventing further catastrophe, one farmer lamented the devastation wrought on his rice fields.

Millions of acres of rich farmland have been flooded by weeks of non-stop rain, but now the Indus is threatening to burst its banks as torrents of water course downstream from tributaries in the north.

“Our crop spanned over 5,000 acres on which the best quality rice was sown and is eaten by you and us,” Khalil Ahmed, 70, told AFP.

“All that is finished.”

Much of Sindh is now an endless landscape of water, hampering a massive military-led relief operation.

“There are no landing strips or approaches available... our pilots find it difficult to land,” one senior officer told AFP.

The army’s helicopters were also struggling to pluck people to safety in the north, where soaring mountains and deep valleys make for treacherous flying conditions.

Many rivers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province — which boasts some of Pakistan’s best tourist spots — have overflowed, demolishing scores of buildings including a 150-room hotel that crumbled into a raging torrent.

The government has declared an emergency and appealed for international help, and on Sunday the first aid flights began arriving — from Turkey and the UAE.

It could not have come at a worse time for Pakistan, where the economy is in free fall.

Prices of basic goods — particularly onions, tomatoes and chickpeas — are soaring as vendors bemoan a lack of supplies from the flooded breadbasket provinces of Sindh and Punjab.

The meteorological office said the country as a whole had been deluged with twice the usual monsoon rainfall, but Balochistan and Sindh had seen more than four times the average of the last three decades.

Padidan, a small town in Sindh, was drenched by more than 1.2m of rain since June, making it the wettest place in Pakistan.

Across Sindh, thousands of displaced people are camped alongside elevated highways and railway tracks — often the only dry spots as far as the eye can see.

More are arriving daily at Sukkur’s city ring road, belongings piled on boats and tractor trollies, looking for shelter until the floodwaters recede.

Sukkur Barrage supervisor Aziz Soomro told AFP the main headway of water was expected to arrive around September 5, but he was confident the 90-year-old sluice gates would cope.

The barrage diverts water from the Indus into 10,000km of canals that make up one of the world’s biggest irrigation schemes, but the farms it supplies are now mostly under water. The only bright spark was the latest weather report, with the met office saying there was little chance of rain for the rest of the week.

Pakistan will consider importing vegetables from arch-rival India to mitigate floods fallout, Finance Minister Miftah Ismail said yesterday, as food prices have risen significantly.

“We can consider importing vegetables from India,” the minister told local Geo News TV.

Turkey and Iran could also be other options, he said.