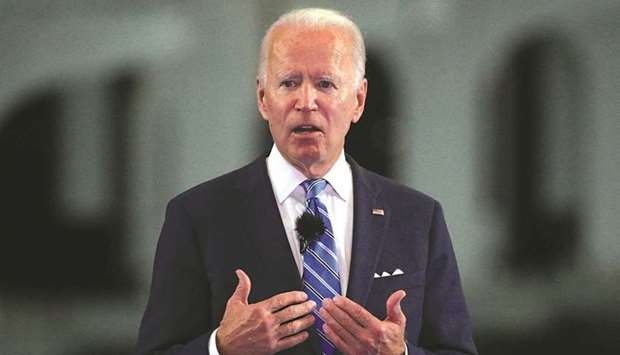

Global events have a way of forcing presidents to focus on defence — even when they’re reluctant to do so. President-elect Joe Biden is unlikely to be an exception, despite his pledge to zero in on fighting the coronavirus and healing the battered US economy.

Here are defence issues likely to confront Biden — and Lloyd Austin, his nominee for defence secretary, if the retired Army general wins Senate confirmation and a congressional waiver from a law that restricts former military officers from taking the top civilian post.

North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un may stage missile tests to compel the new president’s attention to his expanding nuclear arsenal, as he did early in Donald Trump’s term.

In an initial sign that Kim is determined to force his way onto Biden’s agenda, his regime appeared to stage a military parade this month as part of a party congress that declared the US its “biggest main enemy” and predicted that Washington’s “hostile policy” toward Pyongyang would continue.

President Donald Trump lavished Kim with the attention he craved, veering between threats of unleashing “fire and fury,” imposing “maximum pressure” sanctions and claiming that a “love affair” developed in two unsuccessful summit meetings and one brief handshake along the North Korea-South Korea border. Yet the entire time, Kim was building up his nation’s nuclear arsenal and improving on its missile technology.

Biden has criticised Trump’s “made-for-TV summits” and promised “a sustained, coordinated campaign with our allies and others – including China – to advance our shared objective of a denuclearised North Korea.”

Tensions between Washington and Tehran are also high as the Trump era ends. Critics had expressed concern that Trump could order a military strike against Iran, and Iran has made so-far unfulfilled pledges to retaliate for the US killing last year of a top general, Qassem Suleimani.

Biden has pledged to return the US to the multinational nuclear accord with Iran that Trump renounced, and then press to expand its reach. But that won’t be easy. Israel is also determined to dissuade the US from returning to the deal.

Trump’s 2017 National Defence Strategy identified “great power competition” with China and Russia as the defining theme for America’s defence policies, supplanting the concentration on international terrorism that followed the September 11 attacks. That focus is unlikely to change under Biden.

Although the new administration will seek to work with China on issues such as climate change, it also will continue efforts to counter the country’s expanding military presence in the contested South China Sea, as well as its frequent military manoeuvres around Taiwan. The new administration is likely to continue “freedom of navigation operations” at sea, which carry a risk of direct confrontation, as well as close co-operation with US allies such as South Korea and Japan.

Tensions with Russia are also likely to be an early focus after US officials unearthed a sweeping cyberattack on US government and private sector networks for which it holds Russia responsible. US Cyber Command will be central to the military’s efforts to respond to the threat, together with possible sanctions and other retaliatory measures available to Biden.

Although Trump promised to bring American troops home from “endless wars,” Biden will have to weigh the risks involved in extracting remaining US forces from combat zones.

That’s especially true in Afghanistan where, despite a fragile peace accord, an American departure would risk a return to militant rule by the Taliban and potentially a safe haven for terrorist groups including Al Qaeda and Islamic State.

Christopher Miller, Trump’s acting defence secretary, announced on Friday that US troop levels in Afghanistan and Iraq have been drawn down to 2,500 in each country.

While Biden has ruled out calls for major reductions in the military budget, defence spending is nevertheless likely to be flat at best under his administration. Progressive Democrats favour defence cuts in areas such as the US nuclear arsenal to help fund a progressive agenda at home, while fiscal hawks may look to keep spending tight after successive rounds of fiscal stimulus during the pandemic.

Speaking at a virtual event in December, General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the Pentagon’s “desired” real growth in spending of 3% to 5% isn’t likely. He said the Defence Department needs a “reality check” on its likely budgets.

Flat spending will mean tough choices over US military deployments overseas, as well whether to cut back spending on older “legacy” weapons — which have entrenched congressional cheering sections for the hometown jobs they create — in order to pursue more innovative alternatives such as autonomous vessels and robots. It also will raise doubts about the Trump administration’s plan to add 82 new Navy ships over the next five years, 37 more than previously projected.

The military also will continue to play a major role in the fight against Covid-19.

“The next secretary of defence will need to immediately quarterback an enormous logistics operation to help distribute Covid-19 vaccines widely and equitably,” Biden wrote in a December opinion piece in The Atlantic. He said Austin is especially well-suited to the task because he “oversaw the largest logistical operation undertaken by the Army in six decades — the Iraq drawdown.”

Controversy surrounding Austin’s appointment, and the waiver he’d need, highlights another thorny challenge for Biden: the need to heal civilian-military relations, which are arguably more contentious than at any time since the Vietnam War.

During the last year, military leaders resisted Trump’s efforts to call in active-duty troops to quell sometimes violent protests over racial injustice. But National Guard units played a major role in strife-torn cities.

The military’s role in domestic turmoil remains far from settled. Critics said the Pentagon was too slow to mobilise the National Guard to end the riot at the Capitol on January 6, and other Americans may be unnerved by the massive show of force mobilised to head off disruption of Biden’s inauguration.

Within the military, the next secretary of defence will face unresolved social justice questions, from the congressionally approved effort to rename military bases named after Confederate heroes to evidence of far-right extremists among the troops and persistent cases of sexual abuse. — Bloomberg News/Tribune News Service

PROBABILITY: While President Joe Biden has ruled out calls for major reductions in the military budget, defence spending is nevertheless likely to be flat at best under his administration.