Well after the coronavirus pandemic has passed, Europe could find the most damaging economic legacy is not the vast piles of government debt but the hundreds of billion euros in liabilities that have landed on companies.

Businesses were driven to bank loans and bond issues – made affordable by state guarantees and central-bank stimulus – to survive the shutdowns that cut off their cashflows this year. When that crisis support ends, their finances risk being stretched to breaking point, and small firms are already sounding the alarm.

Politicians are being asked to help viable companies clean up their balance sheets, or let them grapple with debt burdens that could cripple investment and job creation for years to come.

“With every week that goes by, the chances of survival for closed businesses are thinning,” said Germain Simoneau, head of the finance committee of French small firm federation CPME. “We’ve never seen a crisis on this scale with systemic risks looming in the background.”

The risk extends beyond the companies themselves. Battered balance sheets could spark a cycle of defaults and bankruptcies that would hit the banking sector and deepen the downturn.

Corporate vulnerabilities “increased sharply” in the wake of the pandemic and were only kept in check by extensive monetary and fiscal support, the ECB said in a pre-released report from its Financial Stability Review, which is due on Wednesday. “An abrupt end to support measures could lead to an increase in financing and rollover risks, thus driving overall corporate vulnerabilities above the level observed at the height of the global financial crisis.”

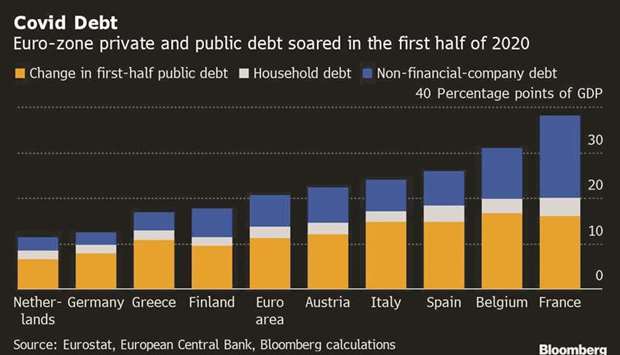

Euro-area companies added more than €400bn ($475bn) in debt over the first half of this year, compared with €289bn in the whole of 2019, according to European Union data. The European Commission warned last week that “servicing debt could be challenging particularly in sectors impacted by the pandemic in a more lasting way.”

Eurochambres, a trade group, found this month that the repayment of debt accrued over the pandemic is the second-biggest concern for businesses. Economists at UBS Group AG reckon default risks among European companies remain elevated despite the exceptional fiscal support. In Germany, which has so far come through the crisis better than most of its peers, the Bundesbank predicts that insolvencies will rise by more than 35% by the first quarter of next year. A survey by SME United, another lobby organisation, showed around half of small and medium-sized businesses in France and Italy are worried about failing.

Economists at Euler Hermes estimate that Italian and French small businesses alone will need €100bn in recapitalisation, on top of liquidity aid.

Ultimately, the solution is probably to persuade European companies to reduce their reliance on bank loans, which they use to a much greater extent than US businesses.

The commission and the European Central Bank have long called for a Capital Markets Union to make it easier to tap alternative funding. ECB President Christine Lagarde said on Friday that such a union is “no longer a ‘nice-to-have,’ it is a ‘must-have’.”

In the medium term though, proposed solutions require government support. That includes tools to improve corporate solvency so viable firms aren’t buried under their debt.

For the smallest firms, that could mean direct fiscal transfers to cope with fixed costs, according to Gerhard Huemer, SME United’s director of economic policy. For the bigger ones, subordinated loans or equity injections would be more appropriate.

Such ideas have struggled though. An EU “solvency support instrument” failed to get enough backing from governments at a summit in July even as they hammered out their blockbuster €750bn recovery fund.

Now the focus is on securing similar kinds of support through the European Investment Bank and other EU programmes, along with national solutions, according to Huemer.

In France, which has seen the biggest surge in corporate debt, from already high levels, the government is preparing a mechanism it hopes will channel around 20bn euros in partial equity to small companies. Backed by a state guarantee, it would involve banks distributing equity loans, mostly refinanced by dedicated investment vehicles.

French banks and the state are still trying to work out how to keep costs low while ensuring returns are high enough to get funds involved. The programme also needs to limit the risk borne by the government, and respect EU rules on state aid.

Spain has a 10bn-euro fund to support larger, strategic firms with subordinated loans, equity and convertible bonds. In Germany, the government is supporting businesses who were forced to shut down with direct cash payments. In fact, Italy and Germany stand out in their use of grants and other aid that doesn’t need to be paid back, according to the EU’s competition chief, Margrethe Vestager.

The European Commission recently loosened its rules on subsidies again so that governments can cover as much as €3mn of companies’ fixed costs. That could be one small step toward an extensive overhaul that reshapes corporate finance for the post-pandemic era.

“Much as the lesson drawn coming out of the 2008-2009 crisis was that banks should be better capitalised and have less leverage, there’s going to be a lesson from this crisis that the same holds for non-financial Corps,” said Michala Marcussen, chief economist at Societe Generale SA.

graph