His dad did 2,000 sit-ups and trained three times a day chasing his track dream around the world. His mom ran her lungs out chasing hers and made national history.

So when their oldest son was 10, his parents delivered a message.

“We’re not paying for college for you,” they told Noah Igbinoghene, the Miami Dolphins’ first-round draft pick.

They gave something more valuable, if used properly.

“He got our genes,” his father, Festus, said. “And he got our work ethic.”

Just for the moment, let’s not talk about who a rookie can be or how he fits this franchise’s future. Let’s talk about how he got here. Because if you see how Igbinoghene arrived to the Dolphins, you can see where he might go.

The genes he inherited helped his parents to international track stardom in their native Nigeria. Faith won a bronze medal at the 1992 Olympics in a sprint relay — the first Olympic medals in Nigerian history. Festus, who also competed in the Olympics, won a bronze in the long jump at the 1990 Commonwealth Games.

As for the work ethic:

“I had a guy come to me recently and say he wanted to be like Noah,” said Festus, who coaches youth sports. “I said, ‘OK, I’ll put you through the workout he does.’ “

The plyometric drills centred on jumping. The sprints. The hopping up and down every other stadium step. The endless drills that became a part of his life since youth sometimes for two, sometimes three sessions a day. “That guy did one day of work and didn’t come back the next day,” Festus said.

These habits haven’t dipped in this odd period where the Dolphins meet by Zoom and their draft class’ first NFL practices were cancelled by the new coronavirus. If anything, Igbinoghene is spurred by pre-draft talk that his cornerback skills were raw due to only playing the position two years.

The switch from receiver at Auburn didn’t surprise him. His barber and pastor mentioned it to him even before Auburn coaches. It took only five practices at the new position as a sophomore to become a starter.

He learned enough that this past year Alabama receiver Jerry Jeudy, the 12th pick in April’s NFL draft, couldn’t get off the line against Igbinoghene and caught just 26 yards of passes in a 48-45 shootout. But he’s still circled some weaknesses to hone the past few months in Atlanta parks with a trainer.

“I’m not the same player I was in my last game (at Auburn),” he said. “I’m better. I’m working hard, still working on things I need to work on. But the player some of the media talked about before the draft — I’m better than that now.”

This work ethic, the one even has his parents telling him to rest on occasion, is his best ally he thinks. “There’s a point where everyone has those genes, everyone runs 4.3s and 4.4s, everyone’s going to be equal to you that way,” Igbinogehene said. “How’re you going to differentiate yourself?

“I really don’t think at this level the game is how fast or how big you are. It comes down to the details and you perfecting your craft. Everyone can run. How do you work?” He grew up running a training hill behind his mom. Faith Idehen was a world-class sprinter who heard in high school there was a chance to gain an American college scholarship.

That became her goal, and she attended Alabama. Her 4x100-meter relay team that won Nigeria’s first Olympic medals came with an on-track celebration that remains on YouTube. Her medal became a show-and-tell prop for her children in elementary school.

She knew Festus from their Nigerian schooldays. He, too, was told he could go to the United States on a track scholarship, but that wasn’t an immediate goal. “I didn’t even know where the US was,” he said.

He attended Mississippi State. Like Faith, Festus became a nurse, sometimes working up to four jobs at a time to help the family. But if the new Dolphins cornerback got speed from his mother and jumping ability from his father and work ethic from both, there’s one piece of genetic inheritance that didn’t transfer: His father’s mouth.

“Noah’s more quiet than I was,” he said. “I competed against (long-jump and triple-jump stars) Carl Lewis and Mike Powell in France. I was talking crap. You win, fine, I’ll shake your hand, but I talked a lot.”

Before an SEC meet, Festus once approached University of Florida long jumper Dion Bentley, who then held the college indoors record. “I said, ‘We’re gonna kick your ass,’ “ Festus said. “That was it. He was done.”

One of the father’s routines actually was passed on when Noah competed in track, winning a national high-school competition in the long jump and competing at Auburn despite football’s demands.

His father clapped his hands over his head before jumping to bring the crowd into his performance.

“One time I told Noah, you truly believe in yourself to get 90,000 people in a stadium clapping and focused on you,” he said. “I didn’t think he would do it. But starting in high school he did.”

As Auburn’s kicker returner, he copied the idea to get fans involved, too. There he was, at the Outback Bowl in his last college game, clapping before returning a kickoff 96 yards for a touchdown.

He was 17 years old when he first started returning them for Auburn. Even now he’s just 20. Raw? Well, he’s young. That’s one of the buying points for the Dolphins. Two more? His parents for the genes they brought, the example they set.

Their disciplined ways sometimes rubbed a teenage Noah wrong. No late nights. No running around. A protected upbringing. And, no, they weren’t going to pay for his college knowing he could work his way there.

Now on the edge of an NFL career, he knows just what he has to do. It’s what he’s always done.

“It’s time to go to work,” he says.

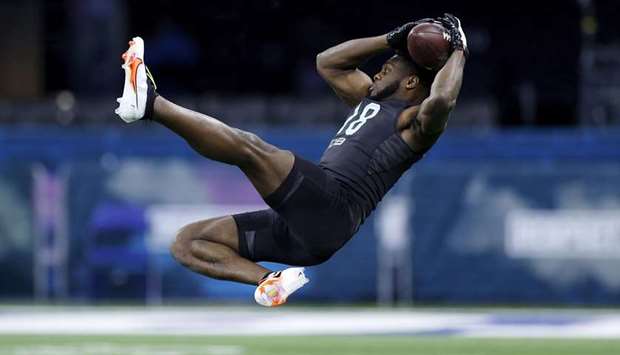

Defensive back Noah Igbinoghene of Auburn runs a drill during the NFL Combine at Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis on February 29, 2020. (TNS)