By Darim al-Basam

In a previous article I tackled the sociology of the pandemic at the individual/ micro level.

In this one my analysis mainly focus on the macro/ structural and institutional level.

With this in mind, it is difficult to resist the temptation of returning back to the French sociologist Michele Foucault when trying to make sense of the proportions of the coronavirus pandemic event.

Comprehending Foucault’s social philosophy and the terminology he coined, like the ones quoted above in the title of this article, is a challenging intellectual task in itself.

Interestingly to note, in the late 1960s Foucault went to teach at the University of Tunis.

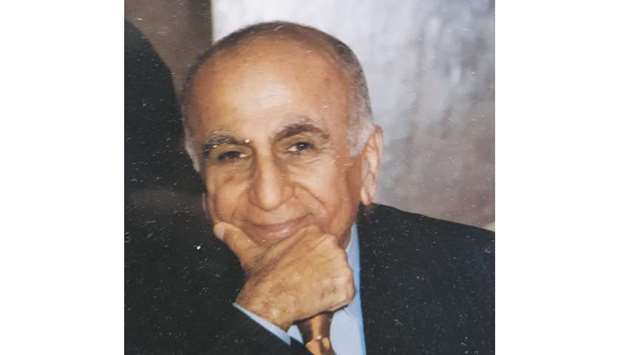

One of the Tunisian faculty members at that time and close friend of mine, the late Abdelkader Zgel told me once

“Foucault was our colleague for three years. We tried to understand his work but we failed. His reflexive thoughts can be quite difficult to define univocally”.

In his article Critique and Experience in Foucault, Thomas Lemke (2011) said: “When life itself becomes an object of politics, this has consequences for the foundations, tools, and goals of political action. No one saw more clearly this shift in the nature of politics than Michel Foucault”. I couldn’t agree more.

Foucault contributed to a critical theory of culture and power and sociology of epidemics, enlarging the scope of the analysis and transforming the methodology.

Initially, I will seek to explain, without attempting to be exhaustive, the main kinds of power relations Foucault explored in his genealogies “, “biopower” and “biopolitics”, as part of “governmentality”, with the associated terms of “sovereignty”, and “discipline, but in a manner tailored to the subsequent analysis of responses to the spread of coronavirus pandemic and the illness it causes.

Today, the human body can no longer lay claim to the radical otherness of nature as distinct from the embedding framework of social systems and culture.

Our relation to life (and biology as a science of life) is always constituted by particular historical frameworks according to Foucault.

In his book (The Will to Knowledge, 1978) he identified the historical transformation to modernity as an epoch in which death no longer bludgeons life.

The “threshold of biological modernity,” he said, lies exactly where life enters history, ushering in “the era of biopower” and “biopolitics”.

Foucault outlined the main contours of the discussion concerning biopower and established a new way to theoretically explore the tension between (make live ) and (let die). For him, the experience of plague is a vital moment in the development of new techniques of power and ways of thinking about the social world.

Plague compels state authorities to take extreme measures to control disease.

Quarantine, of the home, the city, and the nation forces assessments of issues of state power, individual liberty and medical knowledge.

Let us begin with a brief definition of biopolitics and biopower, before situating these concepts within the broader context of Foucault’s discourse and how we can apply his thoughts to explain the sociology of the current pandemic.

Biopolitics can be understood as a political rationality which takes the administration of life and populations as its subject: ‘to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order’.

It functions as strategies specifically related to human vitality, morbidity and mortality; the ways in which authorities and interventions are established that are defined and legitimised as the most effective and appropriate.

Biopower in turn is: A power that exerts a positive influence on life, that endeavours to administer, optimise, and multiply it, subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations.

It thus names the way in which biopolitics is put to work in society and involves what Foucault describes as ‘a very profound transformation of the mechanisms of power’ of the Western classic age towards the enlightenment age.

A move from politics of sovereignty to politics of society ( Rachel Adams 2017 )

Societies,as Foucault puts it, crossed such a threshold when the biological processes characterising the life of human beings as a species became a crucial issue for political decision-making, a new “problem” to be addressed by governments — and this, not only in “exceptional” circumstances (such that of an epidemic), but in “normal” circumstances as well.

A permanent concern which defines what Foucault also calls the “nationalisation of the biological”.

Operationally, the idea of a disease attacking life, according to Foucault, must be replaced by the much denser notion of pathological life.

Here he offers a schematic that conceives of three, coexisting levels of govermentality or, if we want, ‘diagrams’ of power relations in the body politic: (a) a sovereign and juridical power (‘system of legal codes’), (b) a power based on discipline (a shorthand term for a set of non-violent techniques and practices aimed at the regulation of individual bodies and bodily behaviours) and (c) biopolitics or the (apparatus of security). This led in the modern time to an expansion without precedent of all forms of state intervention and coercion.

From compulsory vaccinations, to bans on smoking in public spaces, the notion of biopolitics has been used in many instances as the key to understand the political and ideological dimensions of health policies.

That means, entering the age of modernity, power starts manifesting itself in human urge to control and modify life.

This takes place on two distinct levels: on the level of individuals through disciplinary techniques and on the level of population through bio-power and its techniques ie biopolitics.

Both of these modes of power are aiming to maximise and extract forces from human bodies, in other words, produce life in a given form by utilising techniques of disciplinary subjection and biopolitical techniques of reinforcing life.

But, sovereignty, discipline, biopower and biopolitics, and governmentality in all their diverse forms are in a sense constantly provoked by and in “dialogue” with actual or imagined forms of resistance and struggle. (Kasper Simo Kristensen 2013).

More deliberate and conscious forms of resistance and struggle have also perpetually haunted and called out or co-constructed by the sorts of power relations.

Biopolitics, for Foucault, entail that there is and will be constant conflict between the hegemonic and dominant powerful race and the groups/races that go against its norms inside and outside society.

Biopolitics is usually linked to different political rationalities that govern population according to different principles.

Different rationalities are in a constant state of confronting and modifying each other and this process modifies practices as well.

In the same realm biopolitics is always a politics of differential vulnerability.

Far from being a politics that erases social and racial inequalities by reminding us of our common belonging to the same biological species, it is a politics that structurally relies on the establishment of hierarchies in the value of lives, producing and multiplying vulnerability as a means of governing people.

Biopolitics in this regard does not really consist in a clear-cut opposition of life and death as Foucault put it, but is better understood as an effort to differentially organise the gray area between them.

I can call it “biovulnerability”.

“Institutional racism remains as represented in income inequalities, and all the disparities in education, healthcare and fairness and equal opportunity in general.” (Daniele Lorenzini April 2020).

The current coronavirus outbreak situation is clearly one example of a constellation in which elements of sovereignty, discipline, biopower and biopolitics, under the umbrella of governmentality are combined in uneven (and rapidly shifting) ways.

Much of what in the past was considered exceptional has already gradually entered our daily lives.

Equipped with the foregoing brief discussions of these categories, we can now finally follow up on some of the hints and allusions made above, and untangle some — though, again, not all — of the politics of the coronavirus pandemic situation.

We can begin with the basic rationality of biopower, and with Foucault’s “triangle” of sovereignty, discipline and bioplitics as main aspects of governmentality.

If biopower is structured by the alternative between “making live” and “letting die”, most biopolitics or the security apparatus through which state responses to the coronavirus have been justified publicly by a “re-biologisation” of the population, and a perceived overarching imperative to keep as many people alive as possible.

Some of the most prominent means used to pursue this general end have been the familiar tools of state sovereignty: orders and decrees, quarantining, suspending travels, locking borders, forbidding certain activities, requiring others, and the passing (or suspending) of laws in order to ensure that these measures are legally and constitutionally legitimate or adequately funded.

One aspect of the major debates in the last few months about state measures to curb the outbreak is on the use of biopower to infringe on personal freedom.

Within the logic of liberal governmentality as analysed by Foucault, the security of the population is the constitutive counterpart to its freedom.

Giorgio Agamben, the Italian philosopher who follows Foucault’s school of thought believes that one of the most terrible consequences of a pandemic is the establishment of a state of exception, when the temporarily introduced emergency regime under the pretext of a virus or other emergency event is extended for an indefinite period, and eventually becomes an integral part of the relationship between the state and the population — that is, with constant control and supervision.

Society, according to Agamben, for security reasons, condemns itself to life in an eternal state of fear and insecurity, eventually getting used to it.

Thus, concludes Agamben with reference to Foucault, with strict measures to curb the coronavirus, there is a tendency to use an exceptional position as a normal power paradigm — creating heavy restrictions on freedoms and human rights.

Thinking differently, is Roberto Esposito another Italian philosopher who has written intensively about biopolitics.

In his assessment, it is an exaggeration to talk about the risks to freedom and human rights in the current pandemic crisis.

Most people are doing that willingly.

He believes that the link between politics and biological control has been established long ago, and that there is nothing new here.

The medicalisation of politics is already a fact, as is the politicisation of medicine. ( geopolitica April 2020).

He also proposes to separate Foucault’s discourse from the current specific situation.

In his vision, the situation of tough measures against the coronavirus, especially in Italy, Spain and the United States does not speak of a totalitarian seizure of power, but rather, given the complete confusion before the epidemic, demonstrates the collapse of the current state authorities.

For Fransis Fokoyama, the virus, however, can be considered not only as part of the biopolitical sphere.

It can be seen as something other than the collapse of liberalism and increased control over the population: When the pandemic subsides, the world will have to abandon the usual dichotomy of “democracy VS autocracy”. He believes that it will rather be “some high-performing autocracies VS some with disastrous outcomes.” The main criterion will be not the type of state, but the question of trust. (geopolitica April 2020).

The trust was obvious in the case of Sweden where biopolitics from below was replacing state power and biopolitics from above.

The virus security apparatus was handed to individual citizens in a social responsibility pact.

However this issue is couched, it will bring us to the debate about the second issue that I would like to raise in this article: The “ethics of biopolitical valuation”. We can ask, to the extent that the health and wellbeing of a human population and the individuals making it up continue to be important “ends” of biopower, how exactly are these ends understood?

The term “ends” could conjure up the Kantian ethical principle that human beings are never to be evaluated as “means” but as singular “ends in themselves”.

A contrasting ethical perspective is that of utilitarianism, whereby the good of a population would be understood as the greatest good for the greatest number of people. At its most extreme, utilitarian thinking can inform a Malthusian willingness to let “weak” segments of a population die.

The rationality of biopower could be interpreted according to either of these ways of valuing a population. (Matthew Hannah April 2020 ).

The far right president of Brazil, who is marked by the denial of the scale of the threat, could only muster an impatient shrug last week when confronted by reports about the countries more than 5,500 confirmed coronavirus death in slum areas.

So what? he said. I’m sorry. What you want me to do?

Obviously, it is a ‘let die’ approach and the statement is loaded by racial, colour and white supremacy tone.

We can also see a stark example with different intentions in the initial flirtation of the British government with a policy of “herd immunity”. The UK government’s strategy to minimise the impact of coronavirus “is to allow the virus to pass through the entire population so that we acquire herd immunity”. Implicit in this is the acceptance of large numbers of deaths of vulnerable people; hence Boris Johnson saying that many families will lose loved ones.

This sounds like what Malthus described in 1798 as “positive checks”. It characteristically entails a relation between ‘letting die’ and making live, according to Foucault.

That is to say strategies for the governing of life.

The measures to achieve herd immunity seem to reinforce structural inequalities based on income and status. ( The Guardian 15 March 2020).

Finally, there were some leaders putting political clout ahead of people’s life.

The lax attitude and the reluctance of US President Donald Trump at the beginning to shut down the economy was the fear that it might affect his chances for another term.

“We can’t have the cure be worse than the problem”, he said.

Later on, he realised that politics cannot continue to be politics as usual.

But at a time where the ‘let die’ cost was tremendously high.