Bond investors are looking for orientation points this week in a fog of panic that’s paralysed parts of the world’s biggest and safest debt market.

Roughly $340bn of Treasuries are on the way. That burst of supply could help a market starved of high-quality securities if it lands in less chaotic conditions.

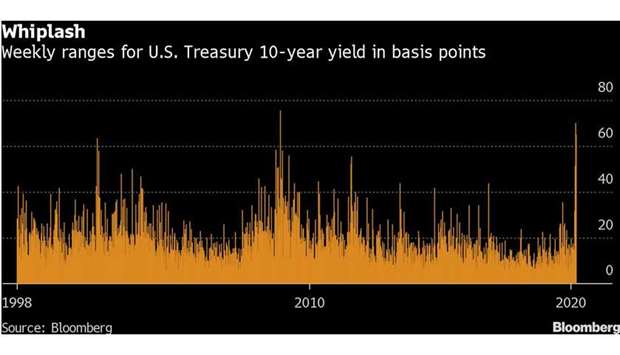

But there’s hardly any guarantee of that: The 10-year yield, a benchmark for global borrowing costs, swung in a range of more than 50 basis points in each of the past three weeks, a phenomenon that hasn’t been seen in the past two decades. Rates-market volatility is not far below a post-2009 high reached this month, and illiquidity still reigns, as seen in shrinking futures open interest.

The days ahead are unlikely to bring much in the way of settling news. Yields pitched lower Friday as more governors ordered residents to stay home to curb the spread of the coronavirus. And investors are also braced for data that will help them piece together the economic fallout. Forecasts for the coming quarters are alarming – Goldman Sachs Group Inc. sees a “sudden stop for the US economy” that will cause an unprecedented 24% contraction in annualised growth next quarter.

“The market is stuck not just because of general illiquidity, the market is stuck because people want to trade on macro fundamentals, and those are still very, very difficult to define right now,” said Seth Carpenter, an economist at UBS and a former Treasury official.

The picture taking shape is one of a rapidly crumbling US economy. Reports on both manufacturing and services are expected to show contraction in March. Thursday brings jobless claims, which are forecast to have more than quadrupled from the previous week to a record above 1mn.

The market’s reaction will be a useful gauge of how much damage traders have already priced into rates, said Lauren Goodwin, an economist and multi-asset strategist at New York Life Investments.

The 10-year Treasury yields 0.85%, after tumbling about 30 basis points Friday in its biggest one-day decline since 2009. It’s still up from a record low of 0.31% set March 9 as global governments pledged trillions of dollars of economic stimulus, and as some investors unloaded even the safest assets to generate cash.

One consolation for investors coming into this week is that central banks have pulled out all the stops. The Federal Reserve has rolled out a series of actions to help stave off a liquidity crisis. Just since last Sunday, its steps include slashing interest rates to near-zero, injecting billions of dollars into funding markets, purchasing $272bn of Treasuries and reviving a string of crisis-era programmes to help companies and banks get cash.

Goodwin doesn’t doubt the ability of monetary authorities to keep funds flowing through the financial system. But she’s concerned the volatility that’s caused a stampede out of corporate bond markets could trigger insolvencies.

“Central banks have signalled very strongly that they are all in,” she said. “The Fed is trying to heal the central nervous system of the market, but the crisis didn’t start there, the crisis started in the real economy because of this shutdown.”

That’s why all eyes are on US lawmakers, with investors looking toward a potential vote this week on a much-anticipated economic rescue package.

“One of the biggest calming impacts on the markets will come from the fiscal policy side,” Goodwin said.

Lawmakers take the spotlight, with a vote looming on a promised spending package. And the push and pull of Treasury auctions and Fed purchases will keep traders busy.

Treasury market graf