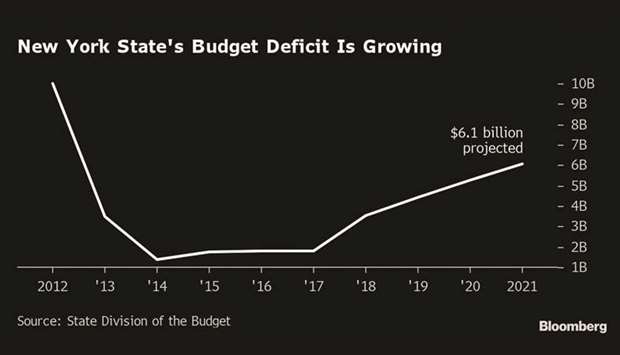

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo may be spending much of the new year explaining how he was caught off-guard by a $6.1bn hole looming in his next state budget, caused mostly by rising Medicaid costs.

It’s the largest gap since Cuomo took office. Amid New York’s recovery from recession, he closed a $10bn gap for the 2011-2012 fiscal year with cuts to health care, education and personnel. This shortfall, disclosed in a report last month, occurred during a strong economy as revenue increased. Critics say the third-term Democratic governor should have known better.

Now, as Cuomo prepares to propose a 2020-2021 budget in January, lawmakers and interest-group advocates are already quarrelling over whether to impose more taxes on the rich or cut services to the poor and middle class. If current spending trends continue, the state would face an $8.5bn deficit in 2023, of which about $3.9bn would be for Medicaid. Cuomo’s budget office says it’s looking for savings.

“While Medicaid spending is projected to grow at almost 6% a year nationally, we are developing a plan to be introduced in January that will once again limit New York State’s Medicaid spending growth and continue high quality care without raising taxes to cover the cost,” said Freeman Klopott, the state budget office spokesman.

According to Moody’s Investors Service, New York’s Medicaid burden is set to increase 6.6% a year through 2023, after five years in which Cuomo-ordered changes reduced annual growth to 2.2%. This year’s increases result from the advent of a $15-an-hour minimum-wage for healthcare workers, a 12% increase in long-term care enrolment and reduced federal aid. Describing the situation as “a credit negative,” Moody’s continued to rate the state’s credit as Aa1 stable.

The gap represents about 6% of the state’s $102bn portion of a current $175bn budget, including federal aid.

The governor should have anticipated these increased obligations, said Andrew Rein, president of the Citizens Budget Commission, a business-supported fiscal watchdog group. Rein is sceptical that Cuomo can fill the gap without deeper across-the-budget cuts, which would require legislative approval. The CBC warned Cuomo earlier this year that Medicaid costs could spike and couldn’t be permanently papered over by the governor’s recent practice of delaying billion-dollar payments into the next fiscal year. Cost controls instituted by the governor eight years ago have failed to stem recent expense increases, Rein said.

“The state’s plan to address the Medicaid-driven budget gap is one part gimmick and one part delay,” he said. “A plan to solve the budget problem need not be done entirely within the Medicaid program. Other portions of the budget also should be considered, including mistargeted aid to wealthy school districts and unproductive economic development programmes.”

Responding to the criticism, Klopott noted Cuomo’s record of cutting Medicaid costs. In 2011, when they were rising more than 13%, he created a Medicaid Redesign Team that capped annual spending growth based on a formula tied to the national medical cost of living. “New York State has kept Medicaid spending growth to less than half the national average – saving taxpayers over $19bn,” Klopott said, “and this has been key to limiting overall state spending growth.”

In the state legislature, Democratic leaders are at odds over new taxes. Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins is against them. Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie is for them. Heastie said he won’t accept cuts in services to the state’s 6mn New Yorkers enrolled in Medicaid who represent about a third of the state population. “We always believe in raising revenue,” he said earlier this month.

The battle may be joined over a revived proposal for a “pied-a-terre” tax on second-home purchases of $5mn or more. The measure, which real estate groups say will hurt an already-weak luxury housing market, would raise about $650mn, said state Senator Brad Hoylman, its chief sponsor, who first proposed it in 2014.

“They use our system of laws to protect their international investment in real estate, and I think there should be a premium on that,” said Hoylman. “This is a way to capture that purchasing power and use it for some common good.”

Spending cuts may also collide with demands for more school aid. Education advocates and teacher-union leaders say the state has failed to comply with a 2006 court order to fully fund its public schools, an obligation that may exceed $3.4bn.

.