Mine closures and employment losses have left deep economic, social and political scars on the main coal-producing regions of the United States and the United Kingdom. Britain’s former coal min ing communities remain among the most deprived in the country decades after the pits closed as they have struggled to attract new industries. Perhaps as a result, there was a close correlation between former coalfields and some of the highest percentage votes for Leave in the 2016 Brexit referendum.

In the United States, the eastern coal regions have above well above average poverty rates and worse outcomes for health and mortality.

Coal communities voted overwhelmingly for candidate Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election, in part because he promised to bring back coal jobs.

Former mining communities in the United Kingdom and the United States tend to blame politicians for the destruction of their industries and economies.

UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1979-1990) and US President Barack Obama (2009-2017) are often held responsible for job losses and their political parties remain deeply unpopular in coal country.

Former coal communities and their economic problems are one of the major battlegrounds in the forthcoming UK general election, and President Trump is relying on them for his re-election campaign in 2020.

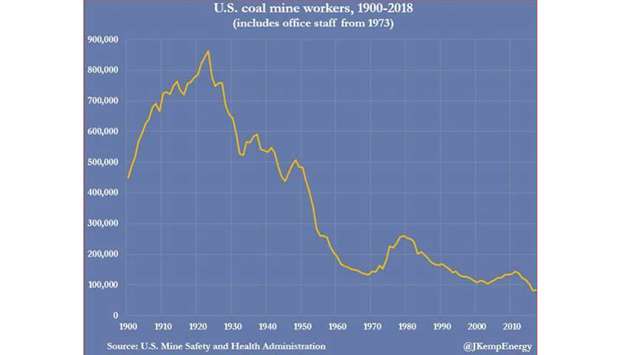

But the historical record shows coalfield employment had been declining for decades before either leader came to power.

Neither leader made much difference to the long-run trend. Increased mechanisation in coal-cutting and loading coupled with other productivity improvements boosted output per hour and reduced jobs rather than political decisions.

British coal employment peaked at 1.25mn in 1920 and had fallen by more than 81% to just 235,000 by the time Thatcher came to power in 1979.

In the United States, coal employment peaked at 863,000 in 1923 and had fallen by more than 84% to 134,000 by the time Obama came to power in 2009. Before 1914, Britain’s coal was almost all cut and loaded by hand, and productivity had actually fallen since the 1880s (“Fifty years of coal-mining productivity: the record of the British coal industry before 1939”, Greasley, 1990).

Mechanisation had started on a very small scale but accelerated rapidly in the inter-war period and throughout the 1950s and 1960s. In 1990, just 1% of British coal was being cut mechanically, but that proportion rose to 13% in 1920, 64% in 1940 and 92% by 1960, according to government statistics. After the Second World War, less than 4% of coal was being power loaded, but that had risen to more than 37% in 1960 and over 90% by 1970.

Mechanisation reduced the number of mining jobs sharply even when output remained steady, and the collapse in employment continued once production started to decline.

In the United States, the sharp rise in the price of fuel oil and natural gas during the 1970s and again in the early 2000s provided a temporary boost to mine employment.

Electricity generators commissioned new coal-fired power plants and idled oil-fired and gas-fired power stations that had become increasingly expensive to run.

But the decline in US gas prices during the 1980s and then the renewed decline after 2008 as a result of the shale revolution brought a shift away from coal-fired generation and a return of coalfield job losses.

In the United Kingdom, the discovery of North Sea gas in 1959 heralded a similar shift away from coal, first in heating in the 1960s/1970s and then in power generation in the 1980s/1990s, with associated job losses. Coalfield employment had come to depend on increasing consumption to help offset the impact of productivity improvements on the number of workers needed to produce each tonne of fuel. Once consumption stopped growing and went into decline, job losses were severe.

Coal employment was lost to a remorseless combination of mechanisation and the natural gas revolution.

In the United States, job losses were accelerated by the shift from small high-cost underground pits in the eastern part of the country to much larger, lower-cost and more mechanised opencast mines in the west.

Coal communities were already experiencing above average levels of deprivation in the middle of the 20th century as employment ebbed away and they failed to attract new industries.

In the United States, the economic problems of one coalfield were detailed in the Report of the President’s Appalachian Regional Commission, originally requested by President John Kennedy and delivered to President Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

n John Kemp is a Reuters market analyst. The views expressed are his own.

.