By Darim Al Bassam

As the birthplace of the 2011 Arab uprisings, we can consider the Tunisian experience of democratic transition as a reference model of political change in the Arab region. In spite of the rough road and tensions that emerged in the first few years that followed the revolution, Tunisia was able to ensure a dynamic public sphere and vibrant freedom of press, to create a pluralist political arena and to establish a civil state based on a democratic constitution adopted by the people’s deputies assembly. Its successful transition did not come from a vacuum.

The country has benefited from several structural advantages, including inheritance of deeply historical modern reforms and associated political culture, a homogeneous population, a politically neutral republic military and security forces, a strong labour and women movements that assure public liberties, and active civil society organisations capable of exercising societal accountability that hold public officials and service providers to account for their action and performance.Based on the above, Tunisia’s democratic transition appeared to benefit from a strong cushion of pragmatism and consensus over the past eight years. The remarkable Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, made up of four civil society groups, was awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for successfully negotiating a way out of a grave political crisis in 2014 when the transition was close to collapse.

The soft landing transition and the absence of violence, however, should not be mistaken for stagnation or a gradual return to the status quo as some politicians thought they can do. Tunisia continues, instead, to experience a deep and meaningful revolution. Since the 2011 uprising, the Tunisian political landscape has shifted significantly as electoral coalitions have been made and unmade, and as established political parties have fractured into smaller parties or collapsed amid leadership disagreements. In this context, the recent rise of the two presidential candidates who won the first round reflect less party platforms and affiliation and more the ambitions of self-styled charismatic figures.

Sociologically speaking, the sweeping changes in the political landscape that the recent 2019 presidential election was able to introduce is similar, in my opinion, to the ‘‘coloured revolutions’ that happened in the former Soviet states more than two decades ago. They all have in common a proposed socio-political transformation intended to introduce ‘democracy from below’.

Although differing in content, they share a common strategy: rebel against the political establishment, mass protests/revolutions occur within the constitutional framework to widen forms of public participation in governance: they are legitimated as a movement for ‘greater democracy’. Additionally, they are all targeted on removing the incumbent political leaderships; and their constituency is formed from a mass base of young people, particularly university students.

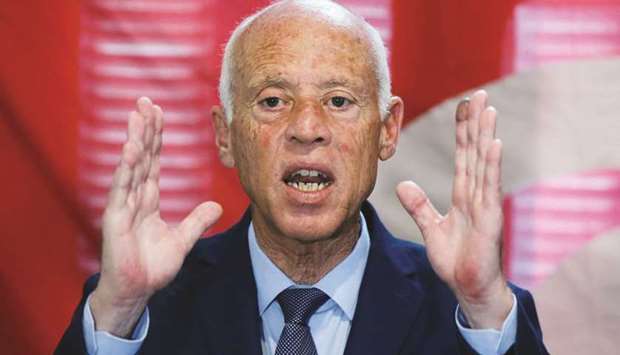

After his landslide win of 72.7% votes, the newly elected Tunisian President Kais Saied said that youth had helped “turn a new page” and promised to “try to build a new Tunisia. Some 90% of 18-to-25-year-olds voted for Saied, according to estimates by the Sigma polling institute, compared with 49.2% of voters over 60. Also, the new president had described his projected victory as a “revolution within the constitutional legitimacy”.

In comparison with traditional political changes, one can notice a novel feature of mobilisation of collective identity and collective action in this generation of political changes. It is done by the orchestration of events through the use of modern media technology – the Internet, mobile phones and assistance from local and foreign media..

More importantly, coloured revolutions have the distinguishing characteristic of a high level of horizontal public participation. They do not fall into the category of vertically ruled classic revolutions because they have no political theory of major social change. The political objective is replacement of elite rather than the substitution of a new ruling class for the existing one and the transformation of property relations.

When we endeavour to analyse this new post election political space in Tunisia, cataclysm, atypical, and rupture are a few words to describe the situation after the results the recent presidential election. Populism is in the national mood as the Arab world’s lone democracy joins the global trend of anti-establishment populism.

Tunisians are looking for leaderships seen as not part of the system and who can promise new ideas, because it hasn’t worked out with those that went before them. Eight years into the Arab Spring, Tunisia’s successive governments had failed to deliver on the primary demand of the revolution: economic opportunity for the underprivileged and horizontal social inclusion of deprived regions. These inequitable and difficult economic conditions have contributed to frustration with not just the ruling parties but the entire political system. This situation has provided ground for the emergence of populist outsiders from the formal political establishment.

But we should be aware that unlike the identity politics or xenophobia emerging in American and European political discourse, these anti-politicians are pitching something uniquely Tunisian: a populism rooted in moral politics of recognition among the youth, in battling poverty, tackling corruption, and empowering local grass root people.

Putting all of this self–triumph aside, the Tunisian experience which belongs to the fourth generation of democracies should be sociologically scrutinised in its trajectory in order to go beyond simplistic interpretations of the dynamics at work. Social science researchers need to put themselves to work in order to investigate the diverse political reconstructions at play in Tunisia. Politics’ bipolarisation has driven rival discourses and rival truths.

I am inclined to label the case of Tunisian emerging trend of populism as “electoral populism”. Populists under this category, like the newly inaugurated president, do not engage in extensive organisation-building activities in either the partisan or civic spheres. They mobilise voters in electoral campaigns without encapsulating them in party organisations, labour unions, or other large-scale secondary associations. The relationship between the leader and populist constituencies is thus direct and largely unmediated by representative institutions. Political loyalty is generated through some combination of emotional attachments, charisma or personal leadership qualities, discursive attacks on established elites, and the promised power transfer to people and distribution of individual or collective benefits.

In order to understand the impact of social dynamics of this new trend, political sociology theories tell us that populist cycles typically occur during periods of political and economic transition that shift or loosen the social moorings of party systems. Populist leadership thrives when social groups, mainly the youth are becoming detached from existing parties and available for electoral mobilisation by political newcomers. This detachment may be attributable to the emergence of new personalities and groups who have never been politically incorporated, or to the rupturing of bonds between voters and established parties. These are precisely the conditions that have existed during the last election in Tunisia.

Consequently, most of the emerging leaders identified as “neopopulist” have mobilised electoral support among atomised or loosely organised popular sectors, and made little effort to penetrate or organise civil society.

Conflict sensitive analysis in Tunisia can inform us that in recent years political challenges to the neoliberal model followed by the ruling collision have grown since it worsen economic and social conditions and was not able to meet social demands that triggered the 2011 uprisings. Meanwhile, the populist discourse of the Marxists leaned Tunisian Left was dogmatic and was not able to produce a well-defined economic alternative. Such dire situation provided opening of political space for new forms of popular mobilisation. Given its organisational malleability and policy flexibility, populism is likely to thrive under these conditions and will remain a central feature of Tunisia’s political landscape for years to come. Far from running its course, the cycle of populism appears to be in full swing in the country.

Moreover, the correspondence between political eras and the level of populist organisation is not uniform, however, suggesting that different patterns of populist mobilisation are influenced but not directly determined by underlying structural and institutional conditions. Whether or not populist leaders organise their constituencies is heavily conditioned by the political alignments and conflicts engendered by their reforms.

To prove this thesis, we can see that in the recent Tunisian election an independent professor of constitutional law achieved a resounding victory in a presidential run-off that could chart a new course for the young democracy. It is a major and rare development for an independent to come out of ‘nowhere’ to overtake candidates from the well-entrenched major parties. In light of this surprising development, many observers have commented that Saied’s success represents a punishment of the major parties and political personalities that have occupied the scene since the Tunisian revolution of 2011 without fulfilling much of the promises made to Tunisians.

The election of Saied marks an end to a hard-fought election cycle that saw political outsiders surge over establishment figures that were blamed for years of socio-economic problems.

Internationally, the new president of Tunisia belongs to the new generation of leaders who advocate participatory and bottom-up democracy. We can see some progressive leaders in Latin America that advocate this line of democracy. “Throughout the world the era of established parties is over,” Saied argued. He proposed devolving power to elected local councils that will decide local spending priorities, with each representative held accountable by the possibility of recall elections.

He is fighting for social change and pushing the democratic imagination to new levels. His populism seeks democracy from below as the real people power. For him, elected representatives seem to provide no real alternative. “Broadening our democratic imagination in this way”, he says, “helps build local movements that are capable of overcoming the inequities existing in our country”. In this regard, the new president has made no secret of his ambitions to amend the Constitution. He has argued for the need to inject forms of direct democracy into Tunisia’s parliamentary system, for instance by choosing representatives from popular Congresses active at the local levels.

From my experience in the development field, this is hard to implement in a situation of weak economy and a lack of appropriate local self organisation and procedural justice. For this modality to properly function, a great deal of research work is needed from Tunisian sociologists and economists to draw out an epistemologically suitable, country-specific community based development models derived from the norms and values of local people, their collectivity and their habitus.

This focus on direct democracy demonstrates the new president’s ideological flexibility. While his profile if far from the ideological world of political Islam, many analysts have recently considered him as the face of a right-wing, social conservatism in Tunisia. Indeed, in many of his positions, he is clearly an expression of the widespread – yet often largely overlooked – social conservatism that characterises Tunisian society.

This conservatism is neither necessarily religious nor rooted in any brands of political Islam according to some sociologists. Still, it is widespread and informs social relations and behaviours at the micro-level not only in rural areas but also in several urban areas which witnessed massive immigration from the interior. Yet, at the same time, he is also supported by many who were historically associated with the extreme left in Tunisia. This has made Kais Saied resemble other contemporary populists which tend to mix right and left-wing inclinations in their political messaging.

Tunisia is historically divided along socio-political (modernists vs traditionalists), and geographic (coast vs interior). Bourgiba’s modernisation system was by nature Urban centred and regionally biased. Regionalism, a widespread sentiment often not addressed openly, remains a crucial element of political, social and cultural identification. The breakeven of electoral data shows that territorial loyalty still orientated the voting behaviour of several groups, but it is slowly eroding. Saied’s victory is rooted in this erosion.

The post-2015 liberal rule by Baji Kaied Sebsi and deterioration of economic situation made the Tunisian people increasingly disillusioned, especially among the new millennial youth. Economic and political stagnation nurtured the feeling that political elites do not act. Or, they act, but only for their own interests. The presidential vote made these grievances crystal clear.

Internationally, the new president of Tunisia belongs to the new generation of leaders who advocate participatory and bottom-up democracy. We can see some progressive leaders in Latin America that advocate this line of democracy. “Throughout the world the era of established parties is over,” Saied argued. He proposed devolving power to elected local councils that will decide local spending priorities, with each representative held accountable by the possibility of recall elections.

He is fighting for social change and pushing the democratic imagination to new levels. His populism seeks democracy from below as the real people power. For him, elected representatives seem to provide no real alternative. “Broadening our democratic imagination in this way”, he says, “helps build local movements that are capable of overcoming the inequities existing in our country”. In this regard, the new president has made no secret of his ambitions to amend the Constitution. He has argued for the need to inject forms of direct democracy into Tunisia’s parliamentary system, for instance by choosing representatives from popular Congresses active at the local levels.

From my experience in the development field, this is hard to implement in a situation of weak economy and a lack of appropriate local self organisation and procedural justice. For this modality to properly function, a great deal of research work is needed from Tunisian sociologists and economists to draw out an epistemologically suitable, country-specific community based development models derived from the norms and values of local people, their collectivity and their habitus.

This focus on direct democracy demonstrates the new president’s ideological flexibility. While his profile if far from the ideological world of political Islam, many analysts have recently considered him as the face of a right-wing, social conservatism in Tunisia. Indeed, in many of his positions, he is clearly an expression of the widespread – yet often largely overlooked – social conservatism that characterises Tunisian society.

This conservatism is neither necessarily religious nor rooted in any brands of political Islam according to some sociologists. Still, it is widespread and informs social relations and behaviours at the micro-level not only in rural areas but also in several urban areas which witnessed massive immigration from the interior. Yet, at the same time, he is also supported by many who were historically associated with the extreme left in Tunisia. This has made Kais Saied resemble other contemporary populists which tend to mix right and left-wing inclinations in their political messaging.

Tunisia is historically divided along socio-political (modernists vs traditionalists), and geographic (coast vs interior). Bourgiba’s modernisation system was by nature Urban centred and regionally biased. Regionalism, a widespread sentiment often not addressed openly, remains a crucial element of political, social and cultural identification. The breakeven of electoral data shows that territorial loyalty still orientated the voting behaviour of several groups, but it is slowly eroding. Saied’s victory is rooted in this erosion.

The post-2015 liberal rule by Baji Kaied Sebsi and deterioration of economic situation made the Tunisian people increasingly disillusioned, especially among the new millennial youth. Economic and political stagnation nurtured the feeling that political elites do not act. Or, they act, but only for their own interests. The presidential vote made these grievances crystal clear.