Australia should consider a “like for like” replacement of its ageing coal plants, the country’s energy minister said yesterday, blaming a turn towards wind and solar for compromising grid reliability.

The comments by the minister, Angus Taylor, are the latest apparent pro-coal push by the government of Scott Morrison, which has embraced the fuel as a key driver of Australia’s economy and a source of reliable power at home and abroad.

They also put the nation’s leadership further at odds with climate-change advocates calling for the closure of the country’s fleet of 21 coal-fired plants and with a business community increasingly funding renewables.

“Record investments in renewables are associated with falling reliability and rising prices,” Taylor told an energy conference in Sydney.

The states of Victoria and South Australia were in the “danger zone,” where dispatchable generation capacity had fallen below levels required to meet peak demand.

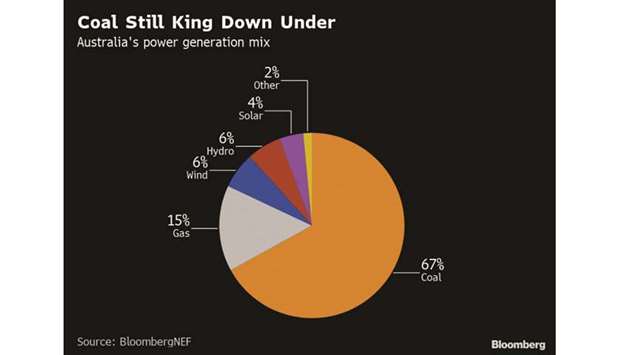

Australia gets around two-thirds of its power from coal, and with several ageing coal plants scheduled to retire over the next decade, the nation either needs replacements that offer the same level of reliability and affordability, or life extensions for existing plants, Taylor said.

“The objective is clear,” he said, adding on the sidelines that he’s focused on cost-effective outcomes, rather than supporting specific technology or fuels.

Australia is likely to need around A$400bn ($270bn) in new utility-scale generation assets over the next 30 years, according to a report Tuesday by the Grattan Institute, a public policy think tank.

The industry broadly agrees that more dispatchable power is needed to back up renewables, but has been frustrated by the lack of clear policy directions from government to promote investment.“A decade of policy inertia” has made it difficult for boards to commit to investing in long-dated assets, Origin Energy chief executive officer Frank Calabria said at the same conference. “Right now, the price of firming energy is not enough to ensure that what we need to make the system reliable will be built.”

Calabria added that the government’s “big stick” energy legislation, which was re-introduced to parliament last month and carries the threat to break up companies that combine retail and generation, was acting as a “hand-brake” on much-needed investment.

Kerry Schott, chair of the Energy Security Board, which was set up by national and state governments to oversee energy market reform, said adding new “flexible and firm” generation should be a priority, but coal wasn’t the answer.

Inflexible coal-fired power stations, which have to keep running during the day even amid abundant solar power, were “dinosaurs” that would become increasingly redundant in the transition to clean power.

The government is backing two major energy infrastructure projects aimed at boosting grid reliability: the A$5bn Snowy pumped-hydro project and a new transmission link between the island state of Tasmania and the mainland.

It also plans to underwrite a raft of new generation projects, most of them either hydro of gas-peaking plants.

Audrey Zibelman, head of the Australian Energy Market Operator, had some sympathy for Taylor’s position: “Governments cannot handle, because people cannot handle, a power system that’s uneconomic or not delivering reliability,” Zibelman told the conference.

It was important to develop an energy market that puts a value on providing flexibility and system security, to help give greater certainty to investment in dispatchable generation, she said.

AEMO, with government backing, is working on plans to develop a day-ahead market to improve price transparency and firm up on-demand capacity.

Under such a system, for instance, a wind farm contracted to supply AEMO with a certain amount of power would have to pay to cover any shortfall if it fails to deliver.

The wind farm could hedge against that risk by entering a supply contract with a gas-fired power plant.

.