Where is all the nickel going? London Metal Exchange (LME) stocks of nickel are falling at an unprecedented rate.

Another 8,898 tonnes left the exchange’s warehouse system on Tuesday, meaning stocks have slumped by almost a third in the last two weeks.

Headline inventory of 108,624 tonnes is the lowest since 2012.

Strip out metal awaiting physical load-out, and “live” stocks of 49,494 tonnes are the lowest since 2008.

Disappearing stocks are adding fuel to the bull fires that were lit when Indonesia announced at the start of September it would bring forward to next year a ban on exports of nickel ore. LME three-month nickel is trading around $17,600 per tonne, up over 60% on the start of the year in sharp contrast to the rest of the base metals, which are mostly in negative territory due to global manufacturing weakness.

The stocks exodus is now creating a rolling squeeze on the London market.

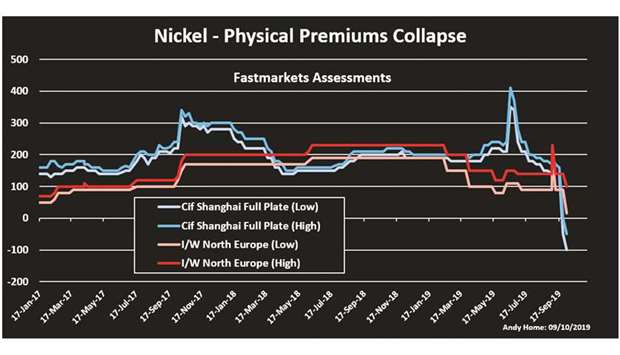

This does not reflect physical supply-chain tightness. Buyers are backing off from the high price with physical premiums imploding.

But it is clear that someone is betting big that the Indonesian ban will generate a supply hit causing real-world tightness in the not-too-distant future.

The super-fast decline in LME inventory is perpetuating the most acute time-spread tightness in over a decade in the London market.

The benchmark cash-to-three-months spread flexed out to backwardation of $240 per tonne earlier this month and the cash metal premium was still valued at an elevated $104 at Tuesday’s close.

The exchange’s positioning reports show a dominant long holding 40-50% of the rapidly depleting “live” stocks.

The spread tightness is supporting the elevated outright price with each daily exchange stocks report reinforcing the bull circle. But there is no current shortage of nickel.

That much is evident from the fact that the backwardation has already sucked in almost 50,000 tonnes of metal since the start of September.

More may be on its way given the negative impact of high outright price and backwardation on physical buying.

Premiums are collapsing, with that for full-plate nickel delivered to China crashing from $140-160 per tonne over LME cash nickel in the middle of last month to a current discount of $50-100, according to Fastmarkets.

The import arbitrage window with the Chinese market has also been slammed shut. China’s imports of refined nickel totalled 28,600 tonnes in August, the highest monthly tally in almost two years.

However, most of the flow, 20,800 tonnes, was classified as “entrepot by bonded area”, implying the metal has made it only as far as Shanghai’s bonded warehouses rather than to a mainland physical buyer.

This LME stocks grab isn’t a reflection of current market dynamics but is rather about potential future market tightness resulting from the cut in the flow of Indonesian ore to China’s mainland stainless steel producers.

It is no secret in the nickel market that a Chinese company has been snapping up LME stocks. Tsingshan Holding Group was the driver of falling stocks in July and is the name in the frame again this time.

The stainless steel producer sits at the heart of the supply conundrum thrown up by Indonesia’s accelerated ban on ore exports. It has led the charge to build out processing capacity in Indonesia.

It is not only the largest producer of nickel pig iron (NPI) in the country but has also built a state-of-the-art stainless steel plant. Indonesia would like more operators to do the same, which is why it has brought forward the export ban to next year.

If nickel miners want to keep operating, they will have to build processing capacity in the country.

Choking off the supply of nickel ore to China’s mainland stainless producers will generate a supply shock to a market already worrying about whether there will be enough metal to meet the expected needs of the electric vehicle battery sector. Calculating the likely impact of that shock is difficult, though, given the number of moving parts in the equation.

How much can Indonesia’s miners ship before the ban comes into force in January 2020? How much can Philippine producers lift their production to compensate? How much stock are China’s stainless producers sitting on? Will higher Indonesian production of processed NPI help fill any supply gap and when? Tsingshan, for one, seems to be betting there will be disruption at some stage of the production chain, generating more demand for the sort of refined metal held in LME warehouses.

It is by no means the first player in the market to take a view on nickel’s bull narrative by hoarding physical stocks.

Ever since LME inventory started falling in 2018, there has been a broad market consensus that some of what has been leaving has simply moved to off-market storage.

n Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.

.