A sharp fall in Japanese physical premiums for fourth quarter shipments is the latest sign that aluminium is not immune from the demand weakness that is sapping the industrial metals complex.

The timing, however, is ironic. Years of chronic overproduction appeared to be coming to an end with global output actually falling so far this year and large off-market stocks finally starting to diminish.

Demand hasn’t been a problem for aluminium in the past, thanks to its growing usage in an automotive sector focused on light-weighting vehicles.

That has changed over the course of this year.

Physical market premiums are confirming what a bombed-out London Metal Exchange (LME) aluminium price has been saying.

Growth in aluminium usage is braking sharply and analysts are starting to downgrade already low price forecasts.

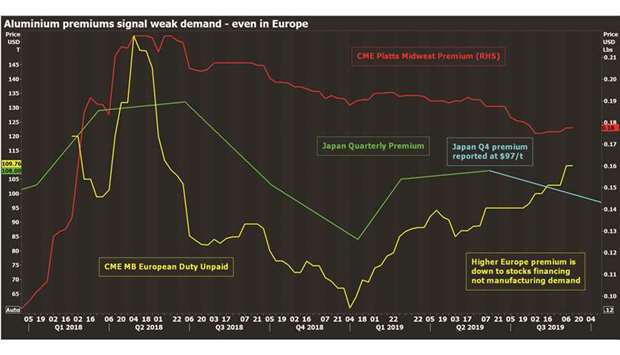

The first reported deal for aluminium shipments to Japan in the fourth quarter has been signed at $97 per tonne over the LME cash price, down from $108 in the third quarter.

Whether that becomes the benchmark deal for regional premiums next quarter remains to be seen, given other Japanese buyers are still trying to negotiate an even lower premium with producers.

The direction of travel, however, is clear.

The premium is going to be set at the lowest level since the first quarter of this year. And this despite the fact that China’s aluminium export surge is abating.

Exports of semi-fabricated products, which jumped by more than 20% last year, rose by just under 6% over the first seven months of this year.

Rather, it’s poor demand in Japan itself that is the main driver of a falling premium. Japan’s domestic shipments of flat-rolled products, extrusions and foil fell by 4.2%, 2.2% and 8.3% respectively in the first half of the year, according to the Japan Aluminium Association.

US premiums have been drifting lower as well, although from a much higher base due to the impact of tariffs.

The CME’s Midwest premium cash contract, indexed against S&P Global Platts’ assessment of the local market, is currently trading just shy of 18 cents/lb ($396 per tonne) compared with over 19 cents ($420) in May.

Here too, product shipments have been sliding to the tune of 1.6% in the first half of the year, according to the US Aluminum Association.

Only Europe appears to be bucking the trend, with the CME’s duty-unpaid premium contract rising to a one-year high of $110 per tonne over LME cash prices. Rather than implying stronger demand, though, higher European physical premiums reflect the re-emergence of stocks financing deals, which reduce the amount of metal available to the spot market.

LME nearby prices are trading at a sizeable discount to further forward prices. The three-month price closed on Thursday at a $31.75-per tonne premium over cash metal. Such a contango structure on the forward curve means easy profits for stocks financiers who “earn” the difference between the two.

In fact, profits just got a bit easier still thanks to the US Federal Reserve cutting interest rates in July for the first time in a decade. LME contango is also a sign of metal availability, even if that’s not immediately apparent from falling LME stocks.

Exchange aluminium stocks, however, have long stopped generating any useful signal about the market’s fundamental dynamics.

They are more a function of storage mechanics together with LME spread gyrations.

The key takeaway is that the European premium is rising on financial not manufacturing demand.

Indeed, stocks financing thrives during periods of surplus metal not supply-chain tightness.

* Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.