Examining the public sector situation in the Arab region yields a complex picture.

Serious malfunctioning patterns emerge, and analysing them collectively can contribute to our understanding of what are the major challenges that the sector faces and what are the ways out.

The reform agenda for the public sector remains large and its full coverage goes beyond the limit space assigned to this article. In order to be more specific and limit the scope, I will focus on the dimensions of civil service reforms dynamics and the challenges they face.

Back into history and following independence, and in order to rectify social inequity, a welfare-oriented social contract between governments and the public emerged in countries throughout the Arab region. This social contract was characterised by a paternalistic view with a leading role for the state which included state planning, protection of local markets versus outside competition and a view of the state in providing welfare, social services, and even employment. Economies became heavily protected and labour markets became highly regulated, with a strong emphasis on employment protection and access to public sector jobs. Businesses developed under the patronage of governments, basically living off the State and benefiting from government contracts and preferential public procurement rules.

Within most of the non-oil Arab countries, the public sector dominated the structure of economic production ever since. Most countries have accumulated over the last decades an overly large civil service stock, especially compared to developing countries in other regions, and the state also participated directly in industrial activities through state owned enterprises.

The importance of these two branches of the public sector has direct fiscal implications in terms of a large wage bill. Indirect effects include efficiency costs arising from bloated and unproductive public enterprises subsidised through soft budget constraints, the resulting crowding out of private sector activity, and public-private segmentation of the labour force which is reinforced by distorted wage and non-wage policies.

As a result, we find now overwhelmingly low value-added employment. Government employment numbers also seem to have grown drastically, in many areas faster than required to deliver services in line with population growth. Much of this has been politically driven, as leaders have sought to reward supporters, head off popular discontent, reinstate staff dismissed by previous regimes, or use the public sector as a social protection mechanism by creating jobs regardless of need, affordability or whether expanding low productivity public sector employment crowds out private sector job creation.

Other causes for the low value added employment have been weak staff control systems, the authorisation of new recruitment outside budget frameworks, and laxly applied staff performance assessment systems, in addition to absenteeism, and the difficulty under civil service rules of disciplining and ultimately terminating poorly performing staff.

Such highly incentivised public sector employment became lately an impediment to economic growth. Many experts argue that the costs associated with a high concentration of public sector jobs will cause lower total factor productivity growth.

Therefore, traditional strategies of utilising public sector employment as a means to soak up excessive labour demands have reached their tipping point. Virtually all countries in the Arab region have civil service laws on their statute books, many of them originating decades ago. In Egypt for example, the employment law that was introduced in the ’60s and confirms the rights of Egyptians to employment in the public sector was until recently in place.

Statistically speaking, one can notice that the public sector in the Arab countries employ anywhere between 14% and 4% of all workers. Survey results show that citizens view government employees as unresponsive and unproductive, poorly trained, prone to absenteeism and with too many officials soliciting bribes in return for services.

Government wage bills are exceptionally high in the Arab region relative to countries’ state of development, whether measured as a share of GDP, or of government revenue and spending. On average, they amount to 9.8% of GDP, but in countries that witnessed the 2011 uprisings like Tunisia for example, the wage bill shot up to 14.1 percentage of GDP. More seriously is the case of Libya. The inexorable increase in the wage bill, has hit 48% of GDP, the highest rate worldwide. The rising wage bill in Libya reflects both salary increases and additional socially motivated hiring. More seriously, a large part of the rising wage bill comes as a result of the use of public payroll to pay for militias, in a context of multi-factional conflict.

As the alarming bells start ringing, the most urgent task of concerned governments in the region is thus preventing the public wage bill from further growing, to avoid destabilising budgets, adding to fiscal deficits and public debt, and undermining public sector performance. In the short run, this means freezing new recruitment (or limiting it to replacements only) and restraining pay awards, even if public sector pay for critical categories of staff remains below the private sector.

But this should go hand in hand with governments adopting income generating development policies and enabling investment environment capable of ensuring jobs for market newcomers in the private sector. In the medium term, governments may find it useful to target the wage bill share of GDP or of total revenues/spending, and aim to bring these ratios down to more sustainable levels. Development of a Medium Term Expenditure Framework would allow a more strategic approach to staffing to be adopted.

Unfortunately, the piece meal ineffective civil service reforms initiatives taking place in Arab countries did not go that way. They typically begin with an effort to review and revise the civil service law, hopefully with the engagement and support of the public service agency. This results in periodic new laws, but by and large the consensus way in which drafts are produced and the power of vested interests results in incremental change rather than a major shift in the way in which the civil service is managed.

Missing from the mix on the conventional civil service policy reviews that Arab governments usually do, is the Ministry of Finance. In most countries budgeting is strictly annual, and a medium term approach is seldom taken. Additional staffing requests are decided by the civil service agency on a needs basis, without taking into account funding availabilities, or forming a strategic view on staffing levels or priorities. Too often, the role of the Ministry of Finance is that of denier of funding. Typically, the way this impasse is resolved is either by reducing the resources allocated to either capital or non-wage operating expenses to make room for salaries, or by postponing pay adjustments, in turn making it more difficult for the government to recruit critical staff in key managerial, technical and professional areas.

In fact, an effective revision of existing civil service legislation may require amendments facilitating better Human Resource Management. This includes reforms which allow government to retrench staff, with equitable compensation, in circumstances where organisational restructuring requires downsizing and existing staff cannot be redeployed elsewhere in the public sector. Facilitating greater mobility of public officials will help match competencies and skills with actual demands across the civil service, improving government utilisation of human resources. In turn, this should enable the government to manage its payroll better. Early retirement and voluntary retirement schemes should be considered, with suitable incentives and safeguards against the loss of key staff.

In a broader perspective, a proper country-specific civil service reform program requires a systems approach and an operationally-useful conceptual framework capable of analysing the country context, power structure, institutions (formal and informal), actors, and processes. System wide reform involves activities seeking to improve the public administration of the State, its roles and functions as well as the effectiveness and efficiency of its core public service institutions in a systemic and sustainable manner.

The emphasis on systemic and sustainable is to underline that the desired socially inclusive reforms bring about enduring changes in the behaviour of public sector actors in the interests of better outcomes for citizens. When planned changes do not institutionalise new or modified behaviours and practices that lead to these better outcomes for citizens, the reforms do not qualify as systemic and sustainable.

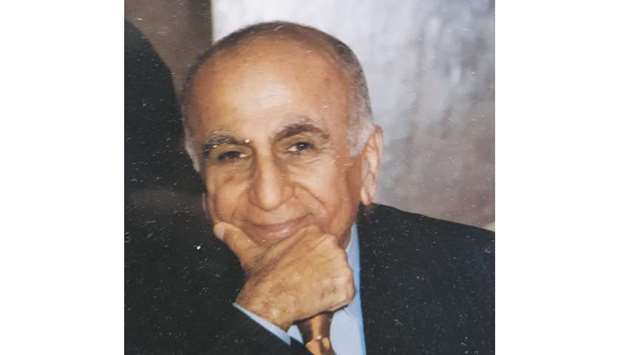

Dr Darim al-Bassam