The first six times I met Richard Holbrooke, I needed to introduce myself. The seventh time we met was in 1983, shortly after I had been named the Wall Street Journal’s managing editor. He not only knew who I was but recalled all our prior meetings. After a mutual friend assured me it wasn’t personal — that Holbrooke was known for always looking over the shoulder of whomever he was speaking to — I decided to ignore the slights and see what happened.

The result was as rewarding as it was improbable. By the time of his death in 2010, our friendship had been real for decades, having endured years when one of us or the other had a big job — or no job. We met frequently in Washington, Connecticut, where we both had weekend homes, and in Washington, D.C. We shared a love of news, diplomacy and international relations. While at the Wall Street Journal, I laughed at his clumsy attempts at becoming an investment banker. He laughed harder when, after years of covering business and finance, I proved myself incapable of running a business of my own. He wrote frequently for Time when I was Time Inc.’s editor in chief. Every assignment was a negotiation. If we agreed to his writing an 800-word, one-page essay, we both knew he would turn in 1,200 words, hoping it would force us to run the column, perhaps including his photo, over two pages.

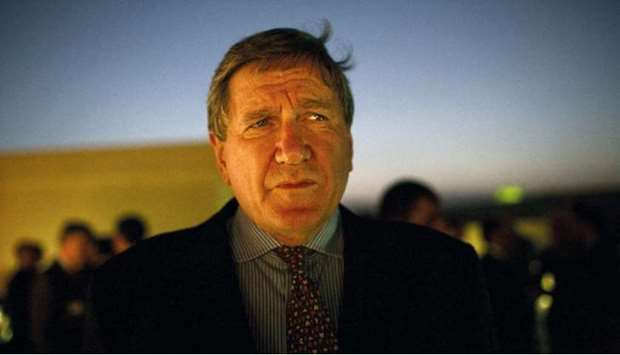

As I read Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century, George Packer’s riveting biography of the diplomat, this memory and others came roaring back to life.

Between 1999 and 2001, when Holbrooke served as America’s ambassador to the United Nations, he made himself and the job seem far more relevant and important than was the case. No matter that it was a consolation prize, bestowed by President Bill Clinton after he denied Holbrooke’s bid to be named secretary of state. The array of guests and the conversation at dinners hosted by Holbrooke and his wife, Kati Marton, made attendees feel that the embassy’s Waldorf-Astoria residence was a true centre of power, and in some respects it was.

Holbrooke also persuaded me to become president of the American Academy in Berlin, the centre devoted to academics and policy that he had established and chaired after serving as America’s ambassador to Germany. I accepted the job after consulting Henry Kissinger, who wisely said, “Whenever Richard asks you to do something, it is less painful to say ‘yes’ than to say ‘no.’” I stayed in the job for two years following his death because every time I sought to quit, I heard his voice, arguing against my doing so.

Packer opens the book with a similar experience: “Holbrooke,” Packer writes, “yes, I knew him. I can’t get his voice out of my head … calm, nasal, a trace of older New York, a singsong cadence when he was being playful, but always doing something to you.”

In Our Man, Packer, who recently joined the Atlantic after years writing for the New Yorker, conducted more than 200 interviews and had exclusive access to Holbrooke’s diaries and private papers. The result is a chronicle of the diplomat’s brilliance, ambition, arrogance and duplicity.

Through his reporting, writing and brilliant personal digressions, Packer delivers a pitch-perfect portrait of Holbrooke the diplomat — from his early years in Vietnam, through his stints as a midlevel State Department official, to his work for President Clinton bringing peace to Bosnia as a special envoy, and his final years trying and failing to gain Barack Obama’s support as a special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan. So too Packer captures Holbrooke’s personal failings as a husband and in his treatment of friends and rivals.

Packer’s asides about Holbrooke’s brilliance are overwhelmed by the lengthy descriptions of the flaws and weaknesses that defined his professional and personal lives. Packer accurately describes, for example, some of the more painful toasts delivered at a dinner at New York’s 21 Club to mark Holbrooke’s 50th birthday. He omits, however, that the evening ended with Holbrooke’s brilliant and extended reply, done from memory and without notes, in which he responded to each toast with humour and grace.

But by the end of the book and of Holbrooke’s life, the reader almost understands why, despite his obvious shortcomings, thousands of mourners, including Presidents Obama and Clinton, and scores of ambassadors and CEOs felt compelled to attend memorial services in Washington or New York for a diplomat who never attained a Cabinet position.

What is harder to accept are the assumptions implied in the book’s title, Our Man, and its assertion that Holbrooke’s life and death symbolise “the end of the American Century.”

Packer’s prologue asserts that as a nation, “Our confidence and energy, our reach and grasp, our excess and blindness, they were not so different from Holbrooke’s.” Yet everything about the book makes clear that Holbrooke, unlike most of us, was so much larger than life that his brilliance, his ambition and his blind spots were singular in nature.

The title Our Man would have been apt were he describing Holbrooke’s relationship with those of us in the press who wrote about and covered him. Packer begins a chapter about Holbrooke and the Obama White House by referring to a profile in the New Yorker that he says missed the mark because it “was too close to Holbrooke’s view of himself.” You have to go to the footnotes to learn that Packer was the author of that New Yorker piece. Holbrooke, who edited Foreign Policy magazine for several years in the 1970s, was that rare diplomat who understood journalists and what drives us. The symbiotic relationship also reflected that many editors thought he was often right on the big issues affecting geopolitics and policy. And he could be great fun, even when he was lobbying for himself. That combination of humour and high purpose also helps explain why so many people who worked for him remained so loyal.

Packer is right in saying that the American Century began with the Second World War, as did Holbrooke’s life. But it is problematic to suggest that the American Century ended with Holbrooke’s death. It is also, at best, an overstatement to assert that anything Holbrooke did — or didn’t do — had that much impact on the decades in which he lived. The “American Century” has been as much about the assertion of democratic principles and the rule of law as about the American exceptionalism that Packer suggests Holbrooke represents. The importance of an Atlantic community has diminished as a Pacific community has risen, but America, despite the best efforts of its most recent two presidents, remains at the centre of the world. Should that change in coming decades, it will be more because of the growth of Asia than the demise of the United States. — Los Angeles Times/TNS

u201cBy the end of the book and of Holbrooke’s life, the reader almost understands why, despite his obvious shortcomings, thousands of mourners, including Presidents Obama and Clinton, and scores of ambassadors and CEOs felt compelled to attend memorial services in Washington or New York for a diplomat who never attained a Cabinet positionu201du2014 Norman Pearlstine