It’s three years since Britain voted to leave the European Union, but the Brexit saga drags on. Departure day has been postponed twice, and what kind of divorce the UK really wants isn’t yet clear. Parliament is deadlocked, having repeatedly rejected the withdrawal agreement negotiated by Prime Minister Theresa May. Now May is on her way out, and the political turmoil is about to get more intense. The risk of a messy no-deal split remains real, and companies continue to spend millions preparing for the worst.

1. Where’s this drama going?

May was trying one more push to get her unpopular Brexit agreement through Parliament. She had offered lawmakers some incentives — including a pledge to let them vote on whether to hold a second referendum if they back her deal — but it looks set to fail. Members of Parliament on all sides of the debate are vowing to reject her latest offer. Euro-sceptics say it’s not a real-enough break from the EU, while europhiles say the split she proposes will be too damaging. May announced her departure yesterday.

2. What’s the endgame?

The next chapter in the drama is a leadership battle inside the Conservative Party — a process that could run all through the summer. There’s a good chance that a pro-Brexit hardliner who wants to rip up May’s deal and even try to lead the UK into a no-deal split could win. That’s because the new leader will be chosen by the 120,000 Conservative grass-roots members, most of whom want a hard Brexit. Former London mayor and Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson is the favourite for now.

There’s also a growing sense that a general election might be needed to break the impasse. By October, Britain could be faced again with the choice between leaving without a deal, asking for another extension or calling the whole thing off. The EU would probably allow another extension but it’s by no means certain.

3. Why the delay and what does it mean?

On April 10, EU leaders granted May a second Brexit extension to October 31, though the UK could leave the bloc earlier if Parliament agrees on a deal. The government says it still aims to exit the EU in the summer. The postponement means Britain will participate in elections for the European Parliament — three years after it voted to leave the bloc. May’s Conservative Party is bracing for a drubbing at the hands of the new Brexit Party, founded by veteran anti-EU campaigner Nigel Farage. May seemed to be hoping that a poor result for her party will encourage Tory members of Parliament to get behind her deal and put an end to the delay that has left voters exasperated. It’s unlikely to work.

4. Can the whole thing be called off?

Yes, and the delay could make that more likely. But there are still major obstacles. At least for now, there isn’t a majority in Parliament behind proposals to hold a second referendum. Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition Labour Party, has come out in favour of another plebiscite, but with reservations. May was adamant that a re-vote would undermine faith in democracy and rip the country apart; she was offering a vote on a second referendum only to win cross-party support for her deal. In any case, it’s not clear what the result would be: Polls indicate that support among voters is now more in favour of remaining in the EU than leaving, but that’s what surveys showed last time, too. Leave ended up carrying the 2016 referendum with 52% of the vote. The UK does have the legal right to cancel the divorce, by revoking the so-called Article 50 notification that triggered the exit process.

5. Could the UK still leave without a deal?

There’s still a chance Britain could crash out of the bloc with no agreement or grace period, though the UK Parliament has voted against that and the EU indicated earlier this year it doesn’t have the stomach for it. May has said she wouldn’t lead the country out without a deal unless Parliament agreed. A hardline pro-Brexit successor to May might try, however. That would leave the UK lacking legal arrangements to smooth trade and other transactions with its neighbours, snarling cross-border commerce. Bottlenecks could bring shortages of everything from food to drugs to manufacturing components. Both sides are preparing for the worst, for example taking steps to prevent a financial-markets meltdown. But while the measures can mitigate some of the more catastrophic outcomes — such as flights being grounded — they won’t address the obstacles to trade that would suddenly emerge.

6. What’s the fallout?

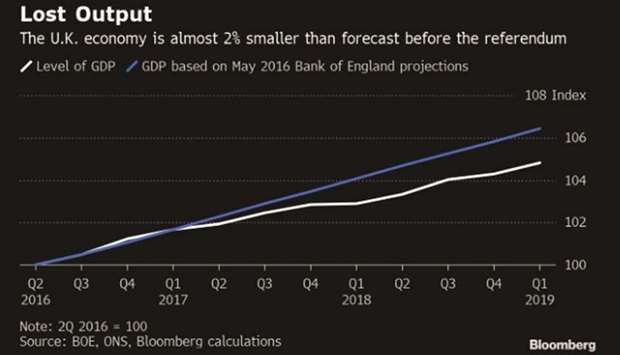

Companies operating in Britain have bemoaned the lack of clarity over Brexit’s impact, warning that unanswered questions about everything from trade policy to immigration laws are throttling hiring and investment decisions. The prospect of Brexit has already prompted global banks to move operations, assets and people to Frankfurt, Paris and other cities. Manufacturers and broadcasters have also started moving facilities, while companies and households have been stockpiling.

7. Why did May’s deal fail?

She faced opposition on all sides: from the pro-Brexit and pro-EU flanks of her Conservative Party, from the Northern Irish party that props up her government and from most of the opposition Labour Party, which wants to maintain trading ties to protect jobs. The main objection was from her own Tories and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party to guarantees that a new physical border wouldn’t emerge between Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK, and the Republic of Ireland, which is in the EU.

Critics say this so-called backstop provision risks binding the UK to EU rules forever. They argue that May caved in to the EU and betrayed the electorate’s call to regain sovereignty, while treating Northern Ireland differently to the rest of the country.

8. What did May’s deal say about future ties?

Alongside the proposed divorce treaty was a non-binding political declaration on what future ties between Britain and the bloc should look like. The declaration was vaguely worded, an intentional move designed then to help May get her deal through a divided Parliament. But that vagueness became a liability as lawmakers complained May was asking them to sign off on a “blind Brexit” — a departure from the EU without a clear sense of what the future would hold. A permanent deal on economic and trading ties was meant to be thrashed out during the 21-month transition that was supposed to start the day Britain left the EU. The political declaration is still on the table and could be tweaked in the unlikely event a new consensus emerges in the UK The EU has said it’s willing to redraft the political declaration but won’t touch the divorce deal — the bit that contains the Irish backstop.

Brexit drama