How do you inspire kids living in impoverished neighbourhoods to rise above their circumstances?

When you’re on the road with the author Dwight Watkins, the answer might include an HBO film crew, presentations by a neighbourhood nachos czar and an internet radio personality, a free lunch and boxes filled with 1,000 copies of the author’s newly released third book, We Speak for Ourselves: A Word from Forgotten Black America.

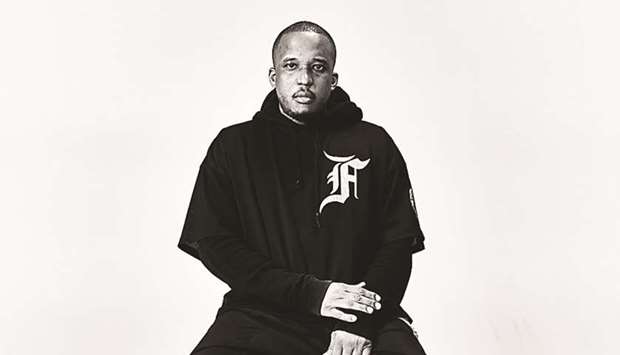

“Reading every day is the only way you can guarantee success for your life,” the 38-year-old author recently told a classroom full of teens in Kerry Graham’s English class at Patterson High School.

“It’s the only way you can grow as a critical thinker. When you learn how to think critically, you learn how to make good decisions. When you learn how to make good decisions, you can do the right things with your life.”

We Speak for Ourselves contains 15 essays about the social ills from underfunded schools to police corruption. It also is Watkins’ attempt to rectify what he says is a serious oversight by other authors who address those topics.

Too often, he writes, intellectuals take “a drone approach” when commenting about economically disadvantaged communities. In his view, these middle-class pundits — some black and some white — hover from above. Rarely do they visit the neighbourhoods whose problems they attempt to analyse or speak to anyone who actually lives in the falling-down rowhouses.

Watkins said he’s not attempting to be the voice of his community, but he feels qualified to be a voice. He grew up and still lives in East Baltimore. He has written about the murder of his older brother and of the period of his life when he ran a successful drug operation. He has described falling in love with books and using that passion to transform himself into the college professor and best-selling author he is today.

Essays with titles such as I’m Sick of Woke and Intellectually Curious or Racist? might seem targeted more toward an adult audience than toward middle and high school students.

But Watkins thinks kids are starved for books by and about people like them, books that address the conditions under which they struggle. It’s terribly important to him to show young people that there are other options than those leading to prison, a life of poverty or an early death.

So he organised his own “book tour” of a dozen city schools aimed at helping students start personal libraries. He brought lunch — supplied by his friend Eric Williams, owner of Nacho Bangers — and he brought along an entourage of East and West Baltimore residents to share their own success stories. Williams, for instance, is 22 years old and bought his business three years ago. Last year, he said, he made a profit of $500,000.

DTLR radio personality and model Tiara LaNiece talked about the importance of finding a career you love and sticking to it. She joined the internet radio station in 2000 at the age of 15 to earn money to purchase the Jordan sneakers she craved.

“Later, I developed my own radio show and after that I did the Nike campaign,” she said. (A photo on Instagram shows her wearing her usual hijab — adorned with the Nike swoosh.) “You can start small and end up big.”

And the HBO crew wielding a great, big boom microphone? They were trailing Watkins for the day in connection with an upcoming and mysteriously vague documentary being directed by Sonja Sohn. (She’s the actor/director best known for portraying Detective Kima Greggs on the Baltimore-based HBO drama, The Wire. Neither she nor anyone else at HBO would reveal the documentary’s topic.)

But chances are that even without the TV crew, the kids in Graham’s class would have been eager to hear what the author had to say.

“D previously gave us 25 copies of his memoir, The Cook Up, and within weeks, every single one had vanished from the classroom,” Graham said. “They disappeared. They were just gone.”

A boy in a hoodie admitted: “I think I might have taken two by accident.”

Graham raised an eyebrow in mock outrage. “By accident?” she said. Then she smiled.

“It’s OK,” she said. “If you’re going to steal something, steal books.”

This mission of getting the right books into the right hands is so important to Watkins that he goes to unusual lengths to accomplish it. On a recent Friday, he crisscrossed the city, squeezing in visits to four schools in four hours.

That was all the time he had to spare. The night before, Watkins had celebrated the official launch of his book at Union Baptist Church and then was at his desk at the University of Baltimore by 8am. the following morning, where he put in two hours crafting a new essay.

Then he was hustling out the door and on his way to his first school. On Friday, he crisscrossed the city with his entourage, squeezing in visits to four schools in four hours. After winding up that day’s book tour at The National Academy Foundation, he bolted for Penn Station, where he was taking a 3:30pm train to Philadelphia where he had an evening book event. He wasn’t staying overnight because the following day he had a meeting in Washington.

With memoir The Cook Up, Watkins takes us deeper into his former life.

It was difficult not to contrast Watkins’ immersive donating style with that of the author of another highly-publicised literary acquisition by Baltimore’s public schools.

Unlike Mayor Catherine Pugh, who reportedly made $800,000 from her Healthy Holly children’s book series, Watkins didn’t profit from his contribution. He said that his publication contract includes a provision that 1,000 copies of We Speak for Ourselves be given to local students for free.

In addition, Watkins made sure that the schools wanted the books before he showed up at classroom doors. In November, he launched a social media campaign inviting teachers and students to compete for copies by submitting poems, essays or posts explaining why their school should receive the books. After receiving a few hundred submissions, Watkins said, a dozen city schools were selected.

During a question and answer session at City Springs Elementary/Middle School, 7th grade student Durius Walker raised his hand.

“What inspires you today?” he asked.

Watkins thought for a second. Then he began to speak very fast, as he does when he feels strongly about what he’s saying.

“You do,” he said.

“You inspire me. I was once your age and trying to figure out the world like you. I needed big brothers and homies to look out for me. Sometimes I had that, and sometimes I didn’t.

“When I have rough days, I know there’s kids running around the city who are being inspired by the work I do so I have to keep going. When you see a young person and you look out for them and they start to succeed — when they are smart and get into great colleges and start their own companies — that is the biggest blessing.”

— The Baltimore Sun/TNS

(Reading is) the only way you can grow as a critical thinker. When you learn how to think critically, you learn how to make good decisions. When you learn how to make good decisions, you can do the right things with your life u2014 Dwight Watkins