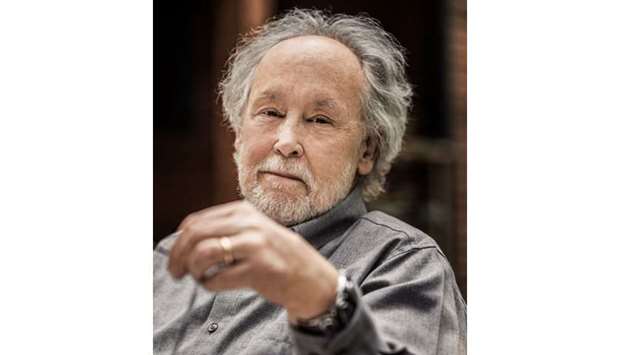

For more than 40 years, Barry Lopez has been one of our great writers on the environment and the human relationship to it.

His prose is beautiful, but what makes his nonfiction books, starting with Of Wolves and Men and his National Book Award-winning Arctic Dreams, so memorable is the sweeping reach of his mind. He makes connections you might never have thought of before, yet they seem inevitable the instant you read them.

That quality permeates his new book, Horizon. Like much of his nonfiction, it’s a book about travel, one of his lifelong obsessions, but this time from an autobiographical angle. At 74, Lopez is looking back at his own life — and forward at the survival of his species, which is not at all a sure thing.

“However it might be viewed,” he writes, “the throttled earth — the scalped, the mined, the industrially farmed, the drilled, polluted, and suctioned land, endlessly manipulated for further development and profit — is now our home.

We know the wounds. We have come to accept them. And we ask, many of us, What will the next step be?”

In search of that next step, Lopez revisits his earlier travels, looking for changes in, and new perspectives on, some of the places he has been. He writes about journeys that have taken him literally from one end of the globe to the other, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, with stops in Oregon, the Galapagos Islands, Kenya, Australia and elsewhere.

He does not travel to easy places. He joins a team looking for meteorites on the Antarctic ice shelf; he meditates on human evolution (and dodges mamba snakes) with archaeologists searching for hominid fossils in the Great Rift Valley. Both trips take him on deep intellectual dives into the past.

Others engage him in more recent history, like his third trip to the Galapagos, the archipelago in the eastern Pacific that fired Charles Darwin’s understanding of evolution. Lopez writes of the beauty he sees there — flocks of flamingos feeding along the beaches, mountainsides dazzling with orchids in bloom — but also finds political controversy over ecotourism, the all-too-common conflict between conservation and profit.

Some places take his thoughts in the direction of what is to come, like a stop at a night market along the Yangtze River in China. On offer for human consumption are “ulcerated fish” from the polluted river, live monkeys and hedgehogs, “wicker trays of dead crickets and heaps of caterpillars … beneath a kind of clothesline from which dozens of sparrow-like birds hung by their feet. This was more than the atavistic scenes of medieval meat markets that Pieter Aertsen painted in the sixteenth century. It was the future, the years to come, when we would begin killing and consuming every last living thing.”

Throughout the book, Lopez returns to the stories of two men of the 18th century, both extraordinary explorers, although one is far more famous: James Cook, the British navigator and cartographer who sailed thousands of miles through largely uncharted waters and mapped many lands previously unknown to Westerners, and Ranald MacDonald, born in what is now Oregon to a Scottish father and a Chinook mother, who in 1848 became the first American permitted to stay in isolationist Japan and teach English to its people.

They are models and touchstones for him not only because they spent their lives venturing to utterly unfamiliar places, armed with curiosity and courage, but because those lives reflect the immense difficulties of communicating across cultures — a communication he believes is an urgent necessity today.

Horizon is an epic journey for readers, 512 pages of text dense with natural and human history, adventure tales and miniature biographies, science of all kinds — biology, geology, anthropology and more — as well as personal memoir.

It’s a book to read slowly and contemplatively despite the urgency of its mission.

Lopez begins Horizon with a sweet vacation sojourn, watching his young grandson play in the waves at a Hawaiian resort. When they visit Pearl Harbour, Lopez tries to explain war to the child and finds his tongue stopped.

The boy “has not yet heard, I think, of Dresden or the Western Front, perhaps not even of Antietam or Hiroshima. I won’t tell him today about those other hellfire days. He’s too young. It would be inconsiderate — cruel, actually — pointedly to fill him in.”

Such knowledge is what we try to protect ourselves from as well. Even when we talk about climate change and environmental degradation, we seldom voice their most personal effects. If the planet becomes unsurvivable, it is not only polar bears and rain forests that will perish. It’s our grandchildren.

Horizon trembles with that message, and with its author’s boundless love for the world he travels.

“It is here,” he writes, “with these attempts to separate the fate of the human world from that of the nonhuman world that we come face-to-face with a biological reality that halts us in our tracks: nature will be fine without us.

“What cataclysm, I often wonder, or better, what act of imagination will it finally require, for us to be able to speak meaningfully with one another about our cultural fate and about our shared biological fate?” —Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida)/TNS

What cataclysm, I often wonder, or better, what act of imagination will it finally require, for us to be able to speak meaningfully with one another about our cultural fate and about our shared biological fate? u2014 Barry Lopez, author