Not since the days of fugitive oil merchant Marc Rich has the commodities trading industry faced so much global scrutiny. The biggest independent oil and metals trading houses, including Vitol Group, Trafigura Group, Glencore, Mercuria Energy Group and Gunvor Group, are facing bribery and corruption investigations in jurisdictions ranging from Brazil to Switzerland and, most importantly, the US.

The multitude of investigations echoes the early 1980s, when then-US attorney Rudy Giuliani prosecuted Rich, founder of the company that became Glencore, for tax evasion and buying oil from Iran in defiance of sanctions. The saga, which brought Rich infamy beyond the obscure world of commodity trading, has long haunted public perception of the industry.

Commodities trading executives now fear US authorities including the Justice Department and Federal Bureau of Investigation are zeroing in once again, according to a dozen interviews with industry officials, bankers and consultants.

The US commodities futures regulator, which hasn’t traditionally enforced foreign bribery laws, has also signalled that it could step into the arena. This month, its enforcement head highlighted what he said was the problem of foreign bribery in commodities markets.

The industry insiders privately worry that law enforcement may seek to make an example of companies that are based in Europe, but operate around the world. There are also concerns that the reliance on middlemen to secure deals in risky countries may have to change. None of the companies have been charged with wrongdoing.

Still, it’s an issue that goes to the heart of the business model of commodities trading. Succeeding in the field has historically meant expertly navigating the unstable nature of resource-rich countries, where corruption is often prevalent, as well as social upheaval, war and logistical perils.

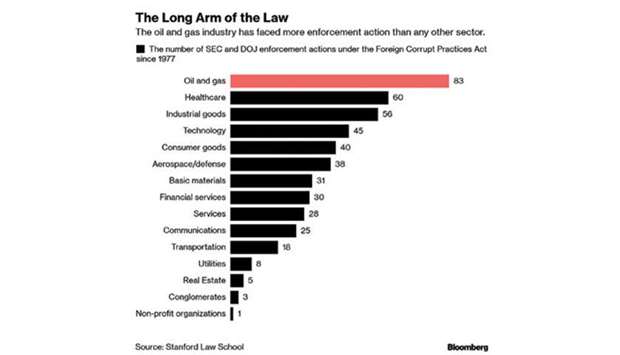

“Oil and gas is the number one industry being openly investigated,” said William Garrett, who manages a legal database tracking cases related to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act at Stanford University in California.

“What we’ve been seeing in the past few years is global cooperation between enforcement agencies, and other countries taking foreign corruption more seriously.” There are at least 17 current SEC, Justice Department and internal investigations into corruption in the energy and mining sectors. That represents a third of the 55 live probes, according to Stanford’s FCPA database.

While energy and mining covers a far wider range of companies beyond trading firms, it does highlight the level of scrutiny over the industry.

The investigations are likely to be a hot topic as executives meet for the annual FT Commodities Global Summit in Switzerland. The biggest traders have spent millions in a bid to improve compliance and become more transparent.

Bankers in commodities trade finance say that the latest round of investigations is a serious issue and may provoke changes. They provide access to the billions of US dollars in short-term loans that fund traders’ day-to-day operations.

The bankers are sensitive to the industry’s legal scrutiny as many of their own institutions have been fined for money laundering and other offences. What are some of the current investigations?

The Justice Department, FBI and Brazilian authorities are studying whether Trafigura, Vitol, Glencore and Mercuria used middlemen to facilitate bribes to win contracts at Petroleo Brasileiro. No charges have been filed against Mercuria, Vitol, or Glencore or any of their executives by Brazilian prosecutors.

Two former executives of Trafigura were charged with bribery. Glencore, the world’s biggest commodities trader was subpoenaed in July by the Justice Department relating to dealings in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Venezuela since 2007.

Switzerland is investigating whether the company failed to properly supervise employees. Last year, a former Gunvor trader was given an 18-month suspended jail sentence after admitting to bribing public officials to secure oil cargoes from the Republic of Congo and Ivory Coast.

Representatives of Vitol, Trafigura and Gunvor declined to comment. All three have said they have a zero-tolerance policy on bribery and corruption. A Glencore spokesman declined to discuss any specific investigations and said the company has an anti-corruption policy and code of conduct. A spokesman for Mercuria declined to comment.

The director of enforcement at the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission said in a speech earlier this month to the American Bar Association that the agency is investigating overseas fraud and manipulation under the Commodities Exchange Act.

“I want to talk about one type of misconduct that can undermine our domestic markets: violations of the CEA carried out through foreign corrupt practices,” James McDonald said in New Orleans. He listed bribes, benchmark manipulation and false reporting among other crimes.

The remarks were meant to put lawyers on notice that the CFTC wants their clients to self-report any potential misconduct in exchange for leniency, said a person familiar with the agency’s thinking. The CFTC plans to create a new initiative to investigate corruption outside the US, copying the Justice Department and SEC, which have had similar teams for years.

The legal trouble is also expensive. For example, Glencore said it spent $24mn in legal fees in just six months last year, from July to December, linked to the Justice Department investigation.

Speaking under the condition of anonymity, one chief executive said that, regardless of the outcome, the investigations are forcing trading houses to rethink their business models, particularly the role of agents.

The industry has long relied on these middlemen, usually local intermediaries who work on commission. The agents can wine and dine well-connected business and government officials in emerging countries with the goal of securing commodity trading deals.

graph