You can’t touch me ‘cause I’m untouchable, Michael Jackson sang on his last real studio album, and for years that appeared to be true.

By the time Jackson released Invincible in 2001, he’d spent nearly a decade dodging suspicions of child sexual abuse. Evidence of his questionable behaviour seemed to abound; a boy accused him of molestation in 1993 before settling the civil case out of court for a reported $23 million.

Yet in many ways nothing seemed to stick to Jackson, perhaps the biggest pop star the world has ever known. Though Invincible didn’t achieve the omnipresence of his earlier work — global smashes like Thriller and Bad, whose influence can still be heard today — the album topped the Billboard 200 and was certified for double-platinum sales.

A second charge of abuse, of which Jackson was acquitted in 2005, failed to dampen enthusiasm for a series of 50 sold-out concerts he planned to perform in London starting in 2009. And his shocking death that year at age 50 only bolstered his appeal, as demonstrated by the success of several posthumous records and shows, including a Cirque du Soleil production on view as we speak at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas.

Now that invincibility may finally be weakening.

On Monday night, HBO concluded its two-part broadcast of Leaving Neverland, director Dan Reed’s searing documentary in which two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, detail the abuse they say they suffered as children at Jackson’s hand.

The singer’s estate has denied the allegations and strongly condemned Reed’s film; it has also filed a $100-million lawsuit against HBO, which the estate accuses of violating a nondisparagement agreement.

But Robson’s and Safechuck’s testimony is so powerful — as horrifyingly graphic as it is persuasively specific — that it’s hard to imagine Jackson gliding past their claims as he did others in the past.

In part that’s because they frame their stories in language that fans can understand.

Again and again in Leaving Neverland, the men describe the experience of being close to Jackson as a kind of hypnosis; so too do their mothers, who shake their heads at the memory of allowing their sons to be in the same bed with a grown man they hardly knew.

But who can’t relate to the idea of being dazzled by Jackson’s talent? As a singer and a dancer and a songwriter, he synthesised the sounds and attitudes of soul and pop — and of black and white — to create a new American music that even now, 40 years after Off the Wall, feels revolutionary.

Of course, as #MeToo has shown us, domination through amazement is a familiar MO among entertainers accused of abuse. Yet Jackson was operating on an infinitely higher level than that of R. Kelly or Ryan Adams; indeed, he presented himself — credibly! — as something of a magical creature, with talismans like his sequined glove and dance moves that seemed to defy earthly physics.

In the late-’80s video game Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker, his feet literally throw off digitised sparks that beat back the bad guys. And what was Neverland Ranch if not the ultimate embodiment of his fairy tale mindset?

There was more troubling stuff too, including the many alterations to his physical body. Still, even when he baffled us or tempted our pity, the effect of Jackson’s supernatural bearing is that we’ve allowed him to live — even after death — beyond a normal code of conduct.

Or at least we did.

Watching Leaving Neverland, one of the revelations that strikes you is the ghoulish yet mundane precautions that Jackson took at his ranch, according to Safechuck, who says the singer had special doors and bells in place to hide their intimate interactions from anyone who might discover them.

That’s not the doing of some otherworldly genius; it’s the sign of a predator who knew the risks of his alleged crimes.

If our perception of Jackson is changing, then, what do we do with his music?

I don’t mean strictly in a moral sense, though that’s certainly part of it. In the streaming era, when every play on Spotify or Apple Music is worth a few fractions of a penny, listeners must accept that interest is tantamount to support — a real shift from the days when problematic figures could be examined (as they should be) without being slowly enriched.

But for Jackson the question is also an aesthetic one: How do we hear his music outside the framework of his untouchability?

So much of Jackson’s catalog is rooted in the exceptionalism of a man who was groomed from childhood for superstardom — and who later, after he’d achieved it, seemed to take on some of the very qualities he’d grown up resenting in his domineering father.

Try to listen to a song like Unbreakable, that defiant Invincible cut, while thinking of Jackson as someone bound by conventional notions of right and wrong. It doesn’t make any sense; the song presupposes that the singer occupies his own moral plane. In a way, though, the same is true of a much older song such as Rock With You, which practically glows with an ebullience simply out of reach for any of Jackson’s peers. The song is magic of a kind, and it’s not as though Jackson had only one trick up his sleeve; the guy made dozens of tunes that seemed to stand apart from the rest of pop, including Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough, Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’, Beat It, Billie Jean, P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing), The Way You Make Me Feel, Smooth Criminal and Remember the Time.

To hear any of them is to be reminded of the others and, therefore, of the singularity of Jackson’s career. And to consider his career is to acknowledge the outrageous leeway we felt his work entitled him to in his personal life.

Leaving Neverland may not prove Jackson’s guilt or innocence. But it demands that we start listening to him as a man, not as an icon. —Los Angeles Times/TNS

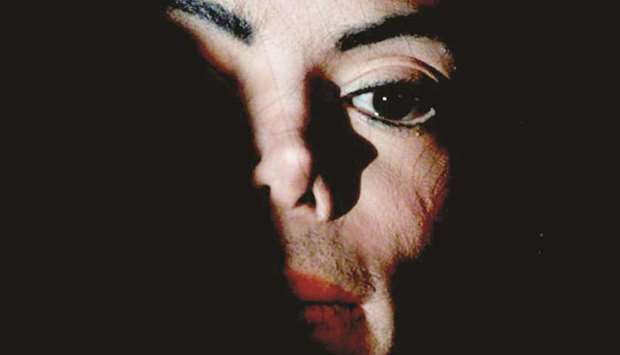

DODGY REPUTATION: Michael Jackson arrives to launch his global initiative Heal the Kids at Oxford University on March 6, 2001.