A look at Russia’s books suggests Vladimir Putin is preparing for war, though not necessarily the kind involving the invincible hypersonic missiles and nuclear torpedoes he’s been bragging about for a year.

Putin’s quietly built a financial fortress that government officials and Kremlin advisers say will safeguard the economy from the escalating salvos they see coming, all while keeping the US and its allies guessing about Russia’s military capabilities and intentions.

It’s a goal Putin’s been pursuing since he rose to power at the turn of the millennium, one that’s gained urgency with each new crisis with the West. During the global credit squeeze a decade ago, Russia’s main stock index lost three-fourths of its value. Five years ago, the rouble halved against the dollar in the wake of collapsing oil prices and the imposition of sanctions over Ukraine, triggering the longest recession of his rule.

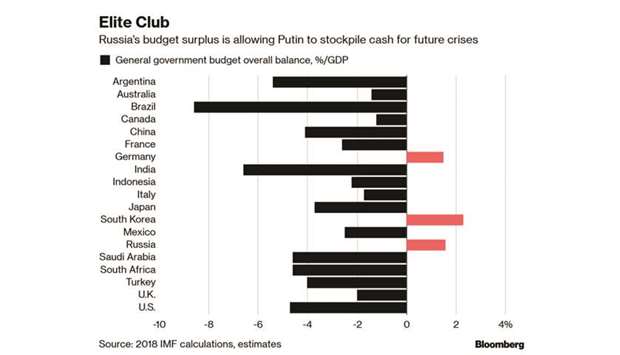

Now Russia is growing again despite adopting one of the most tightfisted budgets of any major economy. This year’s total spending bill, about $270bn, is less than half the Pentagon’s – and Russia is collecting more roubles than it’s disbursing. The country was one of only three in the Group of 20 to run a surplus last year and its debt burden is by far the lowest in the club.

The turnaround can be traced to a decision Putin made at a closed-door meeting with his economic advisers in the fall of 2016 that surprised even the most fiscally hawkish among them, according to three people familiar with the matter. Russia was about to codify a requirement to sequester all oil revenue above a particular price point and Putin chose the most pessimistic scenario presented to him – $40 a barrel, less than half the average for the previous decade.

Instead of loosening the purse strings to appease the competing domestic groups that undergird his system of governance, he yanked them tight. Putin cut spending across the board – including defence – to replenish Russia’s rainy day fund. At the same time, the central bank was refuelling its reserves after abandoning a costly defence of the rouble to focus on amassing gold and yuan, liquidating most of its US Treasury bills without warning.

“Putin is accumulating savings because they give him power,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a political analyst at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “He needs money to fight the West, to deal with intensifying sanctions and to address future economic crises.”

Debt-rating services and financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund are applauding, albeit with caution in light of repeated threats of more punitive action from Washington and Brussels. Moody’s this month followed S&P in restoring Russia’s credit score to investment grade, saying the country’s balance sheet has become bulletproof enough to absorb the likely impact of the additional sanctions its analysts are expecting.

The cost-saving measure was widely opposed in a country where most people were born under communism, leading to a rare outbreak of protests. A hike in the value-added tax is further eroding purchasing power, stoking a rise in consumer debt and deepening public discontent.

“The leadership of our country decided on a highly conservative scenario: save up as much as possible and spend as little as possible,” said Yaroslav Kuzminov, the dean of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. “The goal now is to preserve what’s been achieved, macroeconomic and budget stability, even at the expense of spurring growth.”

A favourite Putin metric—the central bank’s reserves—has risen by about $125bn in the past four years to $475bn. The stockpile, the world’s fifth largest, is still well shy of the $598bn peak reached in 2008, when oil flirted with $150 a barrel. Russia’s sequestration mechanism and wealth fund are modelled on Norway’s system for hedging against fluctuations in crude prices and ensuring future pensions.

But unlike Norway, which rarely taps its $1tn hoard in Oslo, officials in Moscow drain Russia’s pool whenever times get tough, according to Karen Vartapetov, a debt analyst at S&P.

“All previous cancellations of the budget rule were linked to some force majeure,” said Vartapetov. “Russia is now accumulating funds a bit faster that the current oil environment would assume because of the probability of other shocks, including new sanctions.”

To keep the expansion going, Putin is relying more on businesses for investment and less on the multiyear, budget-funded infrastructure projects like those he ordered up for the 2014 Winter Olympics and 2018 World Cup.

He’s made it clear to constituents that he sees Russia as being under siege, both from Western financial centres and Nato forces, but he’s also said that he won’t make the same mistake as the Soviet Union and be goaded into a disastrous spending spree.

Graph 22