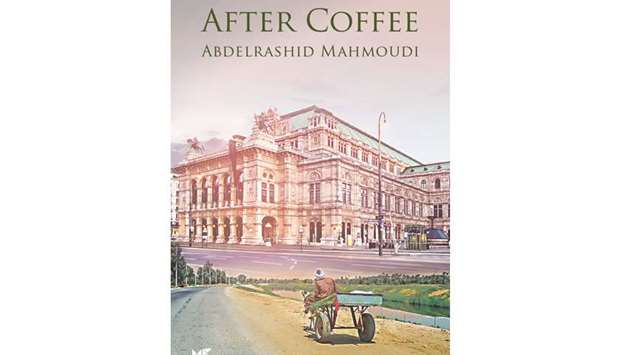

The novel has a long ephemeral story, through a four-decade journey, and reviews the march of its expatriate hero, who was born and raised in a village in northern Egypt, and received his primary education in Ismailia, one of the cities of the Canal, and then moved to Europe, on a long diplomatic career in the country of classical music and international symphonies, Austria, the birthplace of Beethoven and Mozart.

The novel is 421 pages of medium pieces, and is a related narrative trilogy, the first part of which is called the Wolf Killer, in the village of Qawasima in the province of Eastern Egypt, while the events of the second part named the Lost Lamb in the space of the cities of Ismailia and Abu Kabir , the third part, called the Proof, opens in Vienna, capital of Austria.

The author of the novel is the Egyptian writer and novelist Abdelrashid Mahmoudi, a poet, narrator, novelist, translator and researcher in the fields of philosophy, criticism and history of literature, has published a poetry collection and three story collections, and the novel After Coffee is his second novel, after the novel, When the horses cry. At HBKU Press we are committed to providing both our English and Arabic-reading audiences exceptional works of literature,” explains Senior Editor at HBKU Press, Fakhri Saleh in a press statement.

“The translation of this book is especially important as we are highlighting an award-winning literary work in Arabic that spreads knowledge and ideas that are coming out of the Arab world.” he added.

He continued: “This type of cross-cultural communication through translations from Arabic to English is essential as it allows non-Arabic readers the chance to become immersed in the highest level of Arabic literature.”

The event, hosted by OWRI Research fellow in the School of Languages, Cultures, and Linguistics at SOAS, Dr Nora Parr, in a panel discussion on the intertextual exploration of belonging, of Egyptian society, and the Arabic literary past.

The focus was on the books unique investigation of contemporary (post-2011) Egypt that is not ‘dystopian’ or futuristic but rather a story that looks to the past (and not the future) in order to make its commentary on the present.

The translation, however, allowed Nashwa Gowanlock a little more creative license. “I reviewed her Gowanlock’s version wherever she had queries with regard to the original Arabic,” says Mahmoudi. “My comments and revisions were given as mere proposals; and it was left to her to produce the final version. So far, the initial reactions to the translation have been favourable.”

For Gowanlock, staying true to the original text while explaining potentially unknown idioms, phrases, and ideas in a way that English language readers would understand was definitely a challenge. “This is a case of working to maintain the spirit and tone of the work I’m translating,” explains Gowanlock,” focusing on transporting the meaning across, even if that requires taking so-called liberties, or using whichever expressions or turns of phrase are more congruent with the meaning expressed in the source text.