For decades, the pilotless flying devices known as drones were the purview of the military and a cadre of hard-core civilian hobbyists, since they were prohibitively expensive and exceedingly difficult to operate. But an explosion of cheaper computing power, motion sensors and batteries changed all that. Now, inexpensive four-rotor drones have automatic stabilisers that make them easier to fly, and millions are sold worldwide each year. The advent of high-definition cameras and laser-based radar has made them an increasingly tempting bird’s-eye-view tool for farmers checking their crops and insurance adjusters surveying storm damage. Technology behemoths such as Amazon.com Inc and Alphabet Inc are racing to develop drones capable of delivering packages to people’s homes. US federal and local governments are grinding away on rules to accommodate both the swelling demand and the sometimes contradictory need to protect the public’s privacy and safety. Of special concern: roughly 70,000 manned aircraft flights a day in the skies over the US.

The Situation

The US is the largest civilian market for drones and leads the rest of the world by far in investment. Some 944,000 hobbyists have registered at least one drone since the US Federal Aviation Administration began tracking owners in 2015. Another 110,000 people licensed to fly the gadgets commercially have registered 236,000 additional vehicles. The FAA estimates that 1.6mn civilian drones will be sold in 2018. Regulations generally require that they be flown during the day and kept within 400ft (122m) of the ground, within sight of the operator. They’re also generally restricted around airports, military bases, hazardous conditions such as wildfires and sports stadiums during events. Nasa is working on the framework for a low-altitude air-traffic system; some elements, such as the FAA’s capability to grant rapid approvals for flights near airports, are already in place. After complaints from companies that regulations were hindering innovation, the US granted waivers in May at 10 locations to allow tests for uses ranging from inspecting hard-to-reach infrastructure to delivering defibrillators to heart-attack victims.

The Background

Drones can be traced back to World War I. The 1917 Kettering Aerial Torpedo, known as the “Bug,” was designed to fly in a straight line until a timer cut the engine, dropping the plane and its bomb wherever it happened to be. Germany’s V-1 rocket worked much the same way, with better navigation. Military drones can now linger over terrorist dens in places such as Afghanistan for hours at a time and launch missiles — all while under the command of a pilot halfway around the world. It’s one thing to fly in the empty skies of a remote war zone and quite another in the busy airways over the US. In February, a helicopter pilot told investigators his attempts to avoid a civilian drone caused him to crash in South Carolina; the drone pilot was not found.

The Argument

Fears of what drones could do drive the debate over how to regulate them. Security and law-enforcement officials worry about terrorist or criminal attacks with them, anxieties that were heightened after an assassination attempt on Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in August that used two drones rigged with explosives. Government agencies want a mandatory system to identify and track unmanned vehicles. Shenzhen, China-based SZ DJI Technology Co, the world’s largest manufacturer of small drones, supports such a system but wants regulators to track vehicles through their existing radio transmitters, to make compliance simple and cheap. Many commercial operators would prefer adding new transmitters that allow for longer-range tracking. For companies trying to realize delivery-by-drone, such technology will be needed for law-enforcement monitors and automatic collision-avoidance systems. For their part, civil rights groups worry about threats to privacy, which could range from nude photographs taken through bathroom windows to police spying. They have called for rules limiting law enforcement agencies to using drones in emergencies, to collect evidence of a crime or with a warrant. Meanwhile, a legal advocate for states is questioning the federal government’s role. The FAA has historically controlled all manned and unmanned flights and has jealously guarded its authority. The Uniform Law Commission, which promotes standardised statutes for states, has proposed giving land owners the right to airspace above their properties up to 200 feet. This would allow property owners to sue for trespass into their airspace. Some operators say this could penalise commercial uses, such as a real-estate photographer deploying a drone over a property to capture a neighbouring lot.

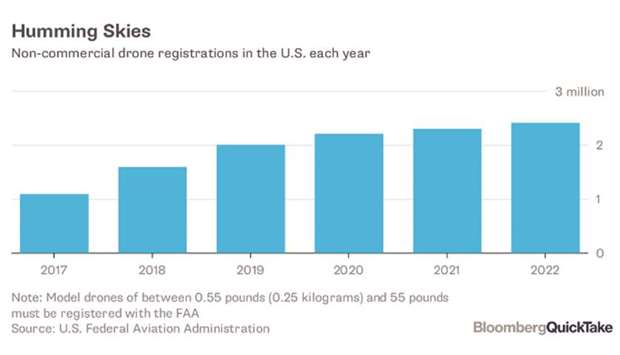

graph