Facing cash flow problems just months before a national election, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi could have a saviour in the country’s new central bank chief.

India’s spending is exceeding its revenue, leaving the government looking for funds to help an ailing banking sector – key to boosting loans and investment and creating jobs. Finance ministry officials estimate the Reserve Bank of India has at least Rs3.6tn ($50bn) more capital than it needs, which they say can be used to help bolster the banks.

“It will be difficult for the government to meet its targets absent substantial new revenue from asset sales or as a transfer from the RBI,” said Sasha Riser-Kositsky, an analyst with Eurasia Group. “The government could also seek to defer some payments into the next fiscal year in order to paper over the deficit.”

Keeping the economic engines firing ahead of a general election next year is crucial for Modi, whose party was rocked by defeats in key regional elections last week. While using the RBI’s surplus capital to support the banks was a point of contention with former governor Urjit Patel, it may not be the case now.

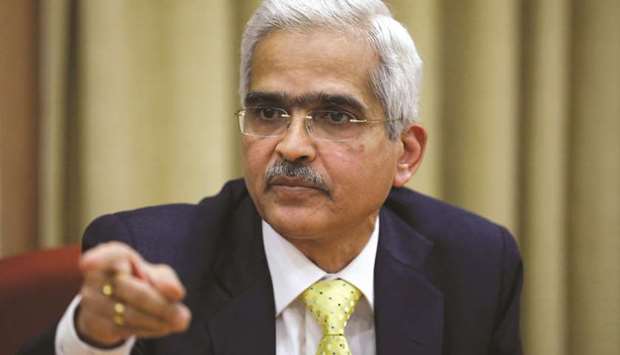

Shaktikanta Das, a former bureaucrat picked by Modi to steer the RBI after Patel’s exit, is open to hearing the government out on its concerns about the economy – whose growth slowed in the three months through September. Getting the RBI to share its capital will help the government boost growth without missing its budget deficit goal of 3.3% of gross domestic product.

While the government has denied having asked for any specific amount from the RBI, the central bank has agreed to form an expert panel to decide on the appropriate level of reserves it should hold.

The government plans to infuse about Rs420bn ($5.9bn) to recapitalise some state-run banks this month. It also has to pay for a healthcare programme and purchase crops from farmers at guaranteed prices.

Everyone agrees that more needs to be done to recapitalise state-run banks, but not all approve of how the administration is going about it. The government’s increasing involvement in the central bank’s affairs could undermine gains in the country’s banking system, S&P Global Ratings said.

Still, with the fiscal deficit having touched 104% of budget estimate in October and revenue from tax and asset sales trailing estimates, the RBI may be Modi’s best hope of swaying voters. Here’s why:

Revenue

With total revenue in April to October accounting for 45.7% of the full-year target and lower than last year’s 48.1%, pressure is mounting on tax authorities and the asset sales department to make good on goals.

Monthly collections of the new goods and services tax have trailed the Rs1.1tn target, and the finance ministry is banking on direct tax to make up for the shortfall.

Sales of stakes in state-run companies have also lagged, with only 42% of the targeted revenue realised so far.

Expenditure

Spending in April to October was 59.6% of the budget estimate. A programme to provide guaranteed prices to farmers for crops is expected to add to the food subsidy bill, while fuel subsidy has risen on higher oil prices.

The cost of a Rs120bn health care programme, which kicked off in September, is expected to be reflected in the fiscal second half. Meeting budget goals may require cutting expenditure, but that may be easier said than done in an election year.

Shaktikanta Das, the new Reserve Bank of India governor, attends a news conference in Mumbai. Shaktikanta, a former bureaucrat picked by Modi to steer the RBI after Patel’s exit, is open to hearing the government out on its concerns about the economy u2013 whose growth slowed in the three months through September.