Mario Draghi chose a curious time to end the European Central Bank’s flagship stimulus programme.

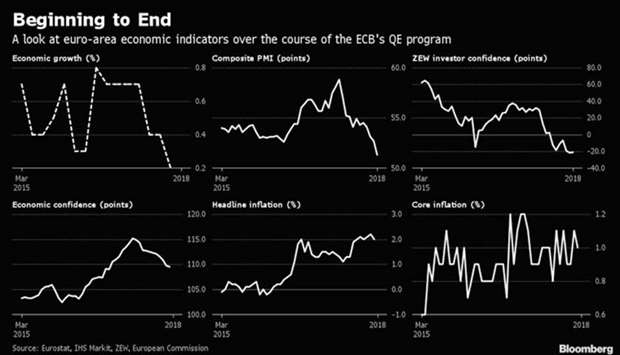

Some of the eurozone’s key economic indicators, including data released on Friday, are worse than they were before the €2.6tn ($3tn) of bond purchases started. Others have barely improved.

While the ECB president can – and does – claim that QE erased the threat of deflation, underlying price pressures are still where they were in mid-2015, just a few months into the programme.

Speaking to reporters on Thursday after announcing that his monetary experiment had run its course, Draghi was asked if the programme had been effective. He admitted that “I’m kind of biased” and said there’s still time to make a fuller assessment – but yes.

“In some parts of this period of time, QE has been the only driver of this recovery.”

When the ECB first announced in June that QE would end this year, it said the programme would add a cumulative 1.9 percentage points each to GDP and inflation from 2016-2020.

Erik Norland, an economist at CME Group, puts the growth contribution a lot closer to zero, noting there was no obvious impact when the central bank slowed the pace of buying.

Research from the Bank for International Settlements suggests the impact diminishes over time.

The ECB has also become increasingly dominant in financial markets, reflected in a scarcity of debt in some parts of the region.

“The time for fire-fighting is over and QE has been brought to an end. Interest-rate guidance is now the active policy tool, talking the yield curve up or down to fine-tune monetary conditions in the euro area,” says Jamie Murray, Bloomberg Economics. Read the latest economic analysis.

QE began months after the US Federal Reserve’s own programme stopped, and the end couldn’t come soon enough for some members who said buying sovereign debt allowed governments to put off fiscal and economic reforms.

Germany’s Jens Weidmann, one of the harshest critics, urged fellow governors this month not to lose any more time in normalising policy. Executive Board member Sabine Lautenschlaeger, also German, as well as Austria’s Ewald Nowotny and Klaas Knot of the Netherlands have likewise called for a speedy unwinding of stimulus.

Yet even as officials unanimously opted to end QE, they cut their economic forecasts for 2019, said risks are “moving to the downside,” and acknowledged threats from protectionism, Italian public finances, and financial-market volatility.

“To justify ending its net purchases, the ECB may have been inclined to downplay the current downside risks to growth,” said Berenberg economist Florian Hense.

“That the ECB had set a high bar for considering an extension of net purchases, and looming German bond scarcity issues, may well have added to the arguments.”

With QE capped but the economy fragile, attention is turning to alternative monetary measures. The top candidate is new long-term loans for banks, which Draghi said were mentioned at Thursday’s meeting but not discussed “in any substance.” He said that will be a topic at a later point.

Graph