1. Why did Patel resign?

While he cited personal reasons, the departure came days before a board meeting on governance, and the appointment of several oversight panels that would allow closer political supervision. Modi also wanted the RBI to ease lending restrictions on some troubled banks, something the central bank has opposed.

2. What was the tipping point?

In October, after the government stepped up its complaints, Patel’s deputy in charge of monetary policy warned of an “economic fire” if the bank’s independence was compromised. A few days later, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley criticised the central bank, saying it “looked the other way” while banks lent indiscriminately in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The government was also said to be examining a never-used law that could allow central-bank decisions to be overridden.

3. What’s at the heart of the dispute?

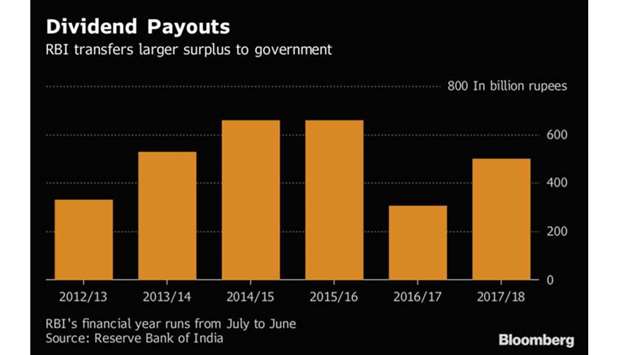

There are two key sticking points: restrictions on banks, and the central bank’s reserves. Patel had continued the bank’s push for more powers to clean up a banking system that’s saddled with bad debts. The central bank has already fenced off 11 weak state-run banks, placing curbs on lending, new branches and dividend distributions, “to prevent further haemorrhaging of their balance sheet” while they’re nursed back to health. The government — the biggest shareholder in 70% of the country’s banking system — wants some of these strictures eased in a bid to kick-start lending that it hopes will support growth. The government has also been asking the RBI to relax capital requirements for banks to free up resources for lending. And Modi’s administration was after the bank’s reserves to help fund its budget goals.

4. What’s the backdrop?

Modi is seeking re-election in early 2019 as the economy grapples with slowing exports and cooling domestic demand. Patel has a doctorate in economics from Yale University, and his term was due to end in September 2019. He rose from deputy in 2016 after predecessor Raghuram Rajan decided to head back to the University of Chicago after only one term. Rajan had faced criticism from a prominent Modi ally who accused the former IMF chief economist of keeping interest rates too high. Many bankers also complained about Rajan’s aggressive efforts to clean up bad debt at state-owned lenders.

5. What are other bones of

contention?

BAD LOANS: The RBI has long tried to get state lenders to recognise soured loans, particularly to the power sector. According to Bloomberg Opinion’s Andy Mukherjee, the Modi government hasn’t exactly co-operated. It even recently appointed an RBI critic to the bank’s board who chided the monetary authority for being too tough in its efforts to get rid of bad debts.

DEADBEATS: The central bank has been leaning on bank managers to cut off “wilful defaulters” — borrowers who have stopped servicing their debt even though they have the ability to pay. This year it introduced rules forcing lenders to declare a borrower delinquent as soon as payments were a day late. The government and power-company officials have lobbied against the rules, and in September the top court temporarily halted legal proceedings against some power producers that were declared delinquent.

TURF: The government has recommended creating a new regulator to oversee payments systems, primarily because it views digital payments as separate from the more traditional sector. The RBI, citing the international model, argues that the payments regulatory board must remain with the bank.