In 2018, South Africa got a new president, two new finance ministers and slumped into a recession. Next year may be even bumpier.

Here’s a look at the key economic and political risk factors to watch out for in 2019:

The budget

After Finance Minister Tito Mboweni painted a bleak picture for finances in October, attention will turn to his plans to boost growth and prevent debt from spiralling out of control at the budget presentation in February. The national budget is a “key pressure point,” Intellidex’s head of capital markets research, Peter Attard Montalto, said in a note. The absence of concrete plans to boost economic growth could trigger a change to negative in the outlook on South Africa’s credit ratings.

Credit rating

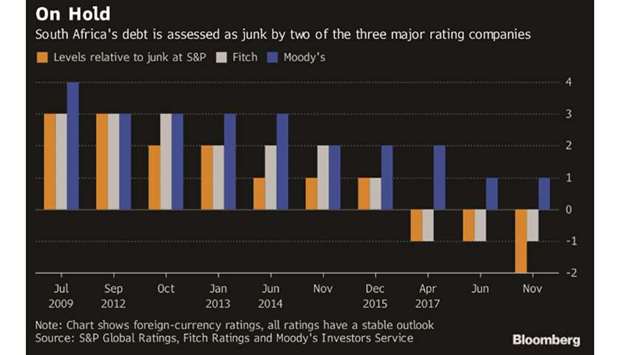

A downgrade to junk by Moody’s Investors Service would trigger forced selling of bonds by investors tracking investment-grade indexes, including Citigroup Inc’s World Government Bond Index. That’s “very likely,” according to David Hauner, Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s head of cross-asset strategy for Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Moody’s didn’t publish a review as scheduled in October, while S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings Ltd have kept their sub- investment grade assessments. Ratings companies may be waiting for the budget data before making another call.

State companies’ debts

Troubled state-owned companies will continue to weigh on the country’s finances, with their combined debt of 1.6tn rand ($113.4bn). Almost half that is guaranteed by the government, the Treasury said in October. Power utility Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd needs 20.1bn rand to meet its obligations in 2019, national carrier South African Airways needs to repay 14.2bn rand by March and the state broadcaster has warned it won’t be able to pay staff unless it gets 3bn rand from the government by February. George Herman, chief investment officer at Citadel Investment Services, predicts a “worst-case scenario” for the companies: the state will have to step in to bail them out, he says.

Expropriation

Lawmakers will report to parliament on March 31 on changes to the constitution to make it easier to expropriate land without compensation. While these steps form part of the ruling African National Congress’s plan to accelerate wealth redistribution, commercial banks that hold farm debt could be hit. Lobby groups are gearing up to fight the process in court and the possible protracted legal wrangling could lead to a period of prolonged uncertainty.

May elections

South African elections have been mostly peaceful and accepted as free and fair since the first all-race ballot in 1994, but the run-up to next year’s vote may see an increase in populist rhetoric and constrain the ANC’s room for manoeuvre. Polls show the ANC maintaining its majority, but the party needs 55% to 60% of the vote to put President Cyril Ramaphosa in a position to implement reforms aimed at reviving economic growth, said Old Mutual Investment Group economist Johann Els. Ramaphosa could overhaul – and shrink – his cabinet after the election.

Reserve bank

The current terms of two of the Reserve Bank’s most senior officials run out next year. While both could be reappointed, the possibility of changes in leadership will add to uncertainty amid a drive by the ANC to make the central bank state-owned. Deputy governor Daniel Mminele’s second term ends in June and governor Lesetja Kganyago’s first five years at the helm ends in November. The governor and his three deputies are appointed by the president: Kganyago has said he’d be available to serve another term if asked; Mminele hasn’t commented.

Graph 3