Bloated by debt, bled by corruption and battered by structurally declining sales, South African power utility Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd is facing what’s known in the industry as a “death spiral.”

And the Johannesburg-based company poses the biggest credit risk to Africa’s most industrialised nation, according to S&P Global Ratings.

More than a decade of unreliable supply and surging prices are driving consumers and businesses off the grid as the price of renewable energy drops, leaving Eskom with lower sales and high fixed costs due to the expense of building new power plants.

The company that supplies 95% of South Africa’s electricity is losing middle-class clients, while arrears from near-bankrupt municipalities climb as many customers in impoverished townships don’t pay their bills or steal power through illegal connections. Rampant corruption and a bloated workforce have pushed total debt to 419bn rand ($30.8bn), and sales volumes – already at a decade-low – are falling, according to interim results reported last week.

“Eskom’s inability to supply electricity and the ever-increasing prices have provided an incentive for users to replace inefficient equipment” and shift to solar panels, Elena Ilkova, a credit analyst at Rand Merchant Bank, said by e-mail. This “will leave Eskom to supply increasingly higher-priced electricity to consumers who can barely afford to pay and many more consumers who either can’t or will not pay,” she said.

With elections about six months away, there’s likely to be little help from the state. On December 1, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni said the government can’t afford any more bailouts and urged Eskom to go back to the bond market. Earlier this year, Public Enterprise Minister Pravin Gordhan intervened when a management plan not to increase pay sparked protests, boosting recurrent costs. Eskom will propose that the government absorb 100bn rand in debt, Sanchay Singla, a money manager at Legal & General who attending a meeting with the company, said.

Going to the bond market is an expensive prospect. The premium investors demand to hold Eskom’s 2026 rand bonds rather than benchmark sovereign securities has more than doubled over the past five years to 124 basis points, even though the debt is government-guaranteed.

Similar to how a burgeoning customer base for telephones in Africa skipped the wait for landlines and started with mobile units, solar panels and other technology leave consumers completely disconnected from Eskom.

“Eskom prices have increased four-fold in nominal terms over the past decade,” said Anton Eberhard, a professor at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business. “And solar prices have fallen 80% since 2011 and 50% for wind.”

The company has publicly acknowledged this threat to demand.

“As new technology allows self-generation to become increasingly price competitive for the consumer, a utility’s sales decline,” Eskom said in its 2018 annual report under the heading, ‘the utility death spiral.’

The cost of servicing Eskom’s annual debt has risen to 45bn rand, equivalent to almost a third of South Africa’s welfare budget, while municipality arrears climbed to 17bn rand from 13.6bn rand in six months. The country has experienced eight consecutive days of rolling blackouts with Eskom struggling to pay for adequate plant maintenance. Khulu Phasiwe, a company spokesman, didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Eskom has been its own worst enemy. In recent years it has, at times, urged consumers to switch to more efficient light bulbs and has subsidised the installation of solar water heaters. Rolling blackouts also reduce revenue. It boosted the number of people it employed by 46% over the last decade to about 47,600 without significantly increasing output. In March, Jabu Mabuza, the company’s chairman, said staff numbers will need to be reduced and it recently started talks to cut senior management.

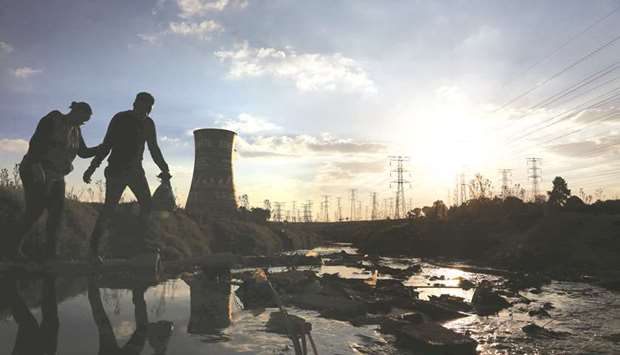

A couple crosses a stream flowing towards electricity pylons and the cooling tower of the defunct Orlando Power Station in Soweto, South Africa (file). More than a decade of unreliable supply and surging prices are driving consumers and businesses off the grid as the price of renewable energy drops, leaving Eskom with lower sales and high fixed costs due to the expense of building new power plants.