When it comes to Beatles nostalgia, the band’s self-titled 1968 White Album has a king-size reputation — the biggest album (30 songs!) by the biggest band in the world at the time. But, to paraphrase a Beatles song, it was all too much, and its producer, George Martin, and at least a couple of its participants, George Harrison and John Lennon, would be among the first to agree.

A half-century later, little has changed, at least in the marketplace for more Beatles. Despite a $138 price tag, a newly released 50th anniversary White Album box set is No. 2 on the Amazon CD/vinyl sales rankings. It’s a 4-pound doorstop: six CDs and a Blu-Ray disc containing the original album, 27 early acoustic demos and 50 session tracks, most of them previously unreleased, plus a hardcover book. The mix, by George Martin’s son, Giles, is immaculate, and in many ways the Beatles have never sounded better or more intimate.

But is the actual music worth the fuss? The pop historians have trained generations to believe the Beatles could do no wrong, and that the White Album was one of the group’s greatest achievements. It undeniably contains some of the band’s finest songs. But does it really make the case for the Beatles in late-career overdrive, or is it a wildly erratic hit-and-miss hodgepodge that could’ve been better served as a single album?

The original The Beatles was packaged for posterity. It spread 30 songs across two discs when released on November 22, 1968, with a white cover designed by pop artist Richard Hamilton. The band’s name was subtly embossed on the sleeve above a seven-digit stamp, as if it were an exclusive art piece. It looked cool, radical, and its sound — both more subtle and more bombastic than anything the Beatles had recorded before — signalled its game-changing objectives.

The ambition belied the turmoil swirling within and around the Beatles at the time. Even though the quartet was coming off the 1967 release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, widely acknowledged as an art-pop landmark, the Beatles’ interpersonal relationships were in disarray.

Band manager Brian Epstein, a stabilising force, died in 1967. A trip to India in early 1968 to visit Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and study transcendental meditation ended with the band members disillusioned and feeling exploited. The world was in a darker time as well. The optimism of the ’67 Summer of Love in which Sgt. Pepper had been released had given way to the Vietnam War quagmire, the Prague Spring Soviet invasion of Poland, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The bleaker, more cynical tone of a number of songs that would eventually appear on the White Album, particularly those of Lennon and Harrison, reflected this crisis atmosphere.

More disruptive changes were in the air. Lennon and Paul McCartney were in the midst of severing ties with their wife and fiancée, respectively, and partnering with new love interests (Lennon with Yoko Ono and McCartney with Linda Eastman). Lennon struggled with heroin addiction and was becoming increasingly estranged from McCartney, his songwriting partner. Harrison and drummer Ringo Starr were beginning to chafe under McCartney’s expanding artistic control. And there was simmering resentment over how much praise was showered on Fifth Beatle Martin for the studio accomplishments of Sgt. Pepper.

Nonetheless, things started promisingly when the band reconvened in May 1968. The quartet took a back-to-basics approach and banged out 27 acoustic demos in Harrison’s home in Esher, Surrey, outside London. The four-track recordings are terrific, the primary reason to dig into the box set as they show the Beatles feeding off a new impulse in rock, the more pastoral feel of recordings by Bob Dylan and the Band that had begun circulating in musician circles. While in India, the Beatles jammed on acoustic guitars, and Lennon and McCartney adopted the clawhammer style of finger-picking they were shown by British folk singer Donovan to craft new songs such as Julia and Blackbird.

The box set also culls tracks from five months of studio sessions that followed the Esher demos. Instead of the sound layering that characterised Sgt. Pepper and the 1966 masterpiece, Revolver, the arrangements remained relatively pristine. The outtakes reveal how Lennon’s characteristically contrarian take on the counterculture, Revolution, evolved into three distinct recordings, two of which appeared on the White Album as the bluesy Revolution 1 and the avant-garde collage Revolution 9, plus a definitive hard-rock take that was released as a single. But other than an early version of Harrison’s While My Guitar Gently Weeps and a ragged but thrilling run through Helter Skelter, the three discs of studio extras will largely appeal only to Beatles obsessives.

In the same way, the White Album now feels more than ever like an indulgence from a band that was no longer in sum-is-greater-than-the-parts collaboration. Lennon was clearly drawing greater inspiration from Ono, who accompanied him to the sessions, than he was from McCartney. Only two weeks before The Beatles was released, Lennon and Ono released their debut album, Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins, with its scandalous nude cover image.

One of the casualties of the widening McCartney-Lennon rift was the checks and balances that the two main songwriters typically imposed on one another’s work. McCartney in particular tossed out some of the flimsiest songs of the Beatles era (Martha My Dear, Honey Pie). Starr inexplicably earned his first songwriting credit on a Beatles recording (the forgettable Don’t Pass Me By), while Harrison continued to feel neglected (not for nothing did he enlist his pal Eric Clapton to play on While My Guitar Gently Weeps, in a last-ditch effort to salvage a song that the Lennon-McCartney brain trust had rejected).

Tensions ran so high that Starr briefly quit the band, recording engineer Geoff Emerick exited the sessions altogether and Martin, feeling underutilised, took an unannounced vacation and left the recording in the hands of fledgling engineers Chris Thomas and Ken Scott.

One of the reasons Martin left was that he felt he was being ignored and wouldn’t be missed, according to a forthcoming book, Kenneth Womack’s Sound Pictures: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, the Later Years, 1966–2016.

The producer never much liked the White Album. As he later told Beatles biographer Mark Lewisohn, “I really didn’t think that a lot of the songs were worthy of release, and I told them so. I said, ‘I don’t want a double album. I think you ought to cut out some of these, concentrate on the really good ones and have yourself a really super album. Let’s whittle them down to 14 to 16 titles and concentrate on those.’”

It was an opinion echoed by Harrison and Lennon. As it turns out, they were right. The White Album would’ve been a classic had it been trimmed to the following 12 keepers. Everything else doesn’t match the high standards the Beatles had previously set for themselves.

White Album keepers

Back in the USSR: A good portion of the album finds the Beatles appropriating and in some case satirising beloved peers and influences, none more so than the leadoff track with its nods to Chuck Berry’s Back in the USA and the Beach Boys’ California Girls. Yet in Starr’s absence, the remaining trio led by McCartney piles on the excitement: piano flurries, exuberant Beach Boys-style harmonies, a wicked guitar solo.

Dear Prudence: Squishy bass, a tolling guitar and harmony vocals swim atop the psychedelic breeze.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Harrison track was nearly orphaned until Clapton came aboard to play the solo, and then it was buried as the seventh track on Side 1. Poor George couldn’t catch a break, but he was right to fight for the song. It’s one of the album’s most enduring moments.

Happiness is a Warm Gun: Lennon’s multipart masterpiece serves as a mini-history of rock ’n’ roll (folk finger-picking, blues chords, hard rock, doo-wop vocals) while skewering America’s obsession with guns in the wake of the King and Kennedy assassinations.

Blackbird: A sparse beauty of a protest song as McCartney’s poignant melody and poetic wordplay allude to the longing and perseverance of the civil rights struggle.

Julia: Lennon’s heartbreaking ode to his late mother casts a dreamlike spell as it yearns for something that could never be.

Yer Blues: The Beatles rarely dabbled in blues, but Lennon dives into the deep end with caustic guitars and cauterising vocals. Even as he parodies white British kids who reverently imitated African-American blues singers, he also one-ups them.

Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey: Clanging bells, agitated guitars, a song pitched on the edge of hysteria as Lennon finds hard-won love amid an atmosphere of tension and paranoia.

Sexy Sadie: Lennon left India feeling used by the Maharishi, and this vicious diatribe does some score-settling. It also inspires one of the singer’s most expressive vocal arrangements.

Revolution 1: Lennon was not a follower. He expresses his scepticism about the counterculture revolution with typical slyness and wit over a deceptively laid-back arrangement that draws on blues and doo-wop.

Helter Skelter: In response to the electric storm whipped up by Jimi Hendrix and Cream, McCartney goes toe-to-toe with the heavyweights. His Little Richard-inspired vocal fights for space amid the heavy-metal carnage of Ringo “I’ve got blisters on my fingers” Starr and the boys.

Long Long Long: Harrison’s spiritual quest has never sounded more haunting.

Contenders: Glass Onion; Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da; The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill; I’m So Tired; Piggies; Rocky Raccoon; I Will; Birthday; Savoy Truffle; Mother Nature’s Son; Cry Baby Cry.

Duds: Wild Honey Pie, Martha My Dear, Don’t Pass Me By, Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?, Honey Pie, Revolution 9, Good Night. —Chicago Tribune/TNS

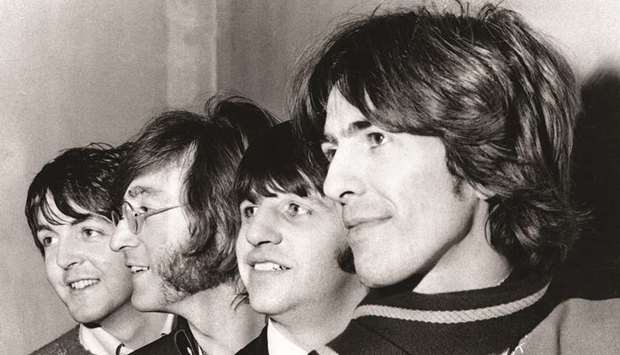

OLD IS GOLD? Pop historians have trained generations to believe the Beatles could do no wrong.